Home > Blog > Environment

Mission Possible: Say No to Plastic

Plastic-wrapped nation. Illustrated by sticker artist Zahnina Jayne Rosal ©2020

Nearly everything we use in our daily lives is made of plastic. We start the day by using a plastic toothbrush. To save money, we pack meals in a plastic container. On the way to the office, we pick up coffee in a disposable cup, which sometimes comes with disposable plastic straw. At the office, we attend a meeting that serves water, juice, or soda in PET bottles.

These modern conveniences seem harmless but in abundance, compounded by habitual improper waste disposal, is how the world has found itself nearly suffocated in plastic.

Single-use plastic is everywhere

According to a United Nations environmental report, “Our planet is drowning in plastic pollution. Around the world, one million plastic drinking bottles are purchased every minute, while up to 5 trillion single-use plastic bags are used worldwide every year.” Half of these plastics are manufactured as single-use products, eventually discarded to contribute to the 300 million tonnes of plastic waste and debris the world produces annually.

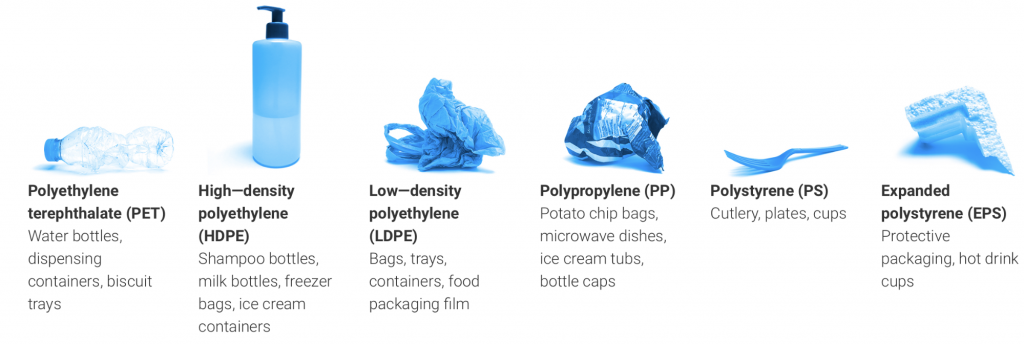

Different types of plastics (grabbed from UN Environment Report)

Different types of plastics (grabbed from UN Environment Report)

These plastic pollutants degrade into smaller fragments—from undetectable microplastic (>5mm) about the size of sesame seeds, to macroplastic (<5mm) large enough to be easily recognized in its original form. These find their way into catchments before being discharged to rivers, seas, beaches, and recently, even in remote, pristine locations like Lake Geneva in Switzerland and Lake Guarda in Italy.

The world is so littered with plastic that a recent study has indicated the presence of small pieces of plastic waste even in the remote mountain ranges of the French Pyrenees. Samples found from the mountains include microplastics likely from single-use plastic packaging from take-out food and PET bottles transported through the air.

The throw-away culture and soft plastics

In the Philippines, soft plastics are the most prevalent plastic litter found in our waters, according to Amy Slack, an environmental consultant who regularly volunteers for Marine Conservation Philippines to work with international movement Break Free From Plastic in Negros Oriental initiative. In her analysis of plastic waste collected during their group’s beach cleans in December 2019, she blogged: “Consistently, the vast majority of the debris we found strewn across the beaches across the Philippines was plastic; a significant amount of that was soft plastics which can’t be recycled – plastic bags, sweet and crisp packets, and single-use soap and detergent sachets. There were some variations though: at one beach, we kept picking up a staggering amount of styrofoam.”

Sachets are non-recyclable multilayered, single-used plastic. © Amy Slack

Sachets are non-recyclable multilayered, single-used plastic. © Amy Slack

Recycling facility in Quezon City, taken during a field visit last February 2020. © Czarina Constantino / WWF-Philippines

Recycling facility in Quezon City, taken during a field visit last February 2020. © Czarina Constantino / WWF-Philippines

Though their organization was able to fish out trash and segregate, another road block cropped up. According to Slack, “It became increasingly apparent that part of the problem was the variability of waste management across the municipality of Zamboanguita, in the Negros Oriental province.” Aside from the lack of resources or end-points, many locals have no recycling knowledge at all. This seems to be the case not only in the municipality of Zamboangita, Negros Oriental, but also around the country.

Meanwhile, Czarina Constantino of World Wide Fund for Nature Philippines (WWF), also the national lead for “No Plastics in Nature” Initiative acknowledges this. “Meron ‘pag Luzon, pero ‘pag mga Visayas or Mindanao, Hirap sila. Kasi archipelagic pa rin tayo. Sobrang hirap rin para kulektahin ang mga basura. Sobrang gastos. (There are in Luzon, but they’re scarce in Visayas and Mindanao because our country is archipelagic. It is very challenging to collect garbage. It’s very expensive.)

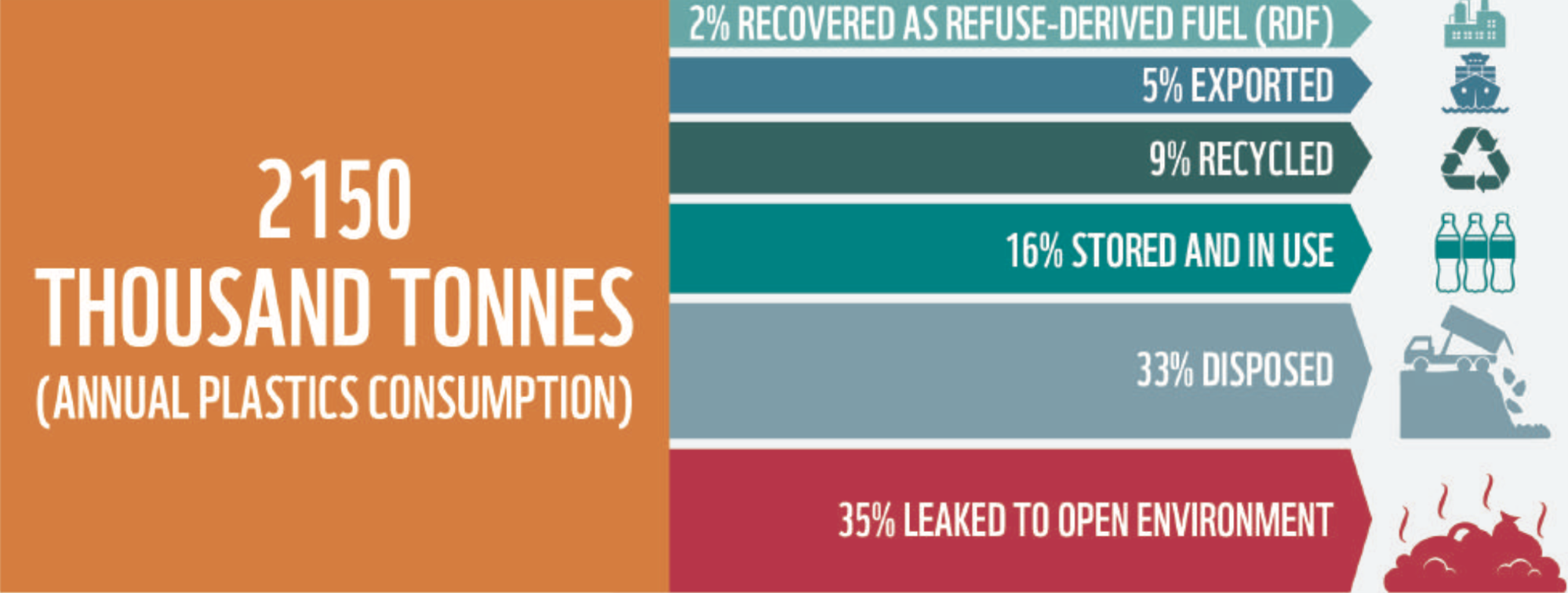

The number of recycling facilities in the country is too limited to accommodate all the plastic waste the country generates, which is about 20 kilograms per person annually, or 2,150,000 tons of plastic waste in 2019, according to the 2020 WWF findings from its recently conducted material flow analysis of plastic packaging waste.

Flow of Plastic Materials in the Philippines in 2019 © WWF Philippines

Flow of Plastic Materials in the Philippines in 2019 © WWF Philippines

Sachets, Extended Producers Responsibility and eco-design

Sachets are made of several layers of different types of plastic, which require separation prior to recycling. Some of these layers have very poor recyclability, and with all the mechanical steps required to separate them, it is neither economical nor profitable to recycle sachets. It is decidedly a single-use product, and a good number of case studies suggests it to be the likely culprit to our environment’s plastic woes.

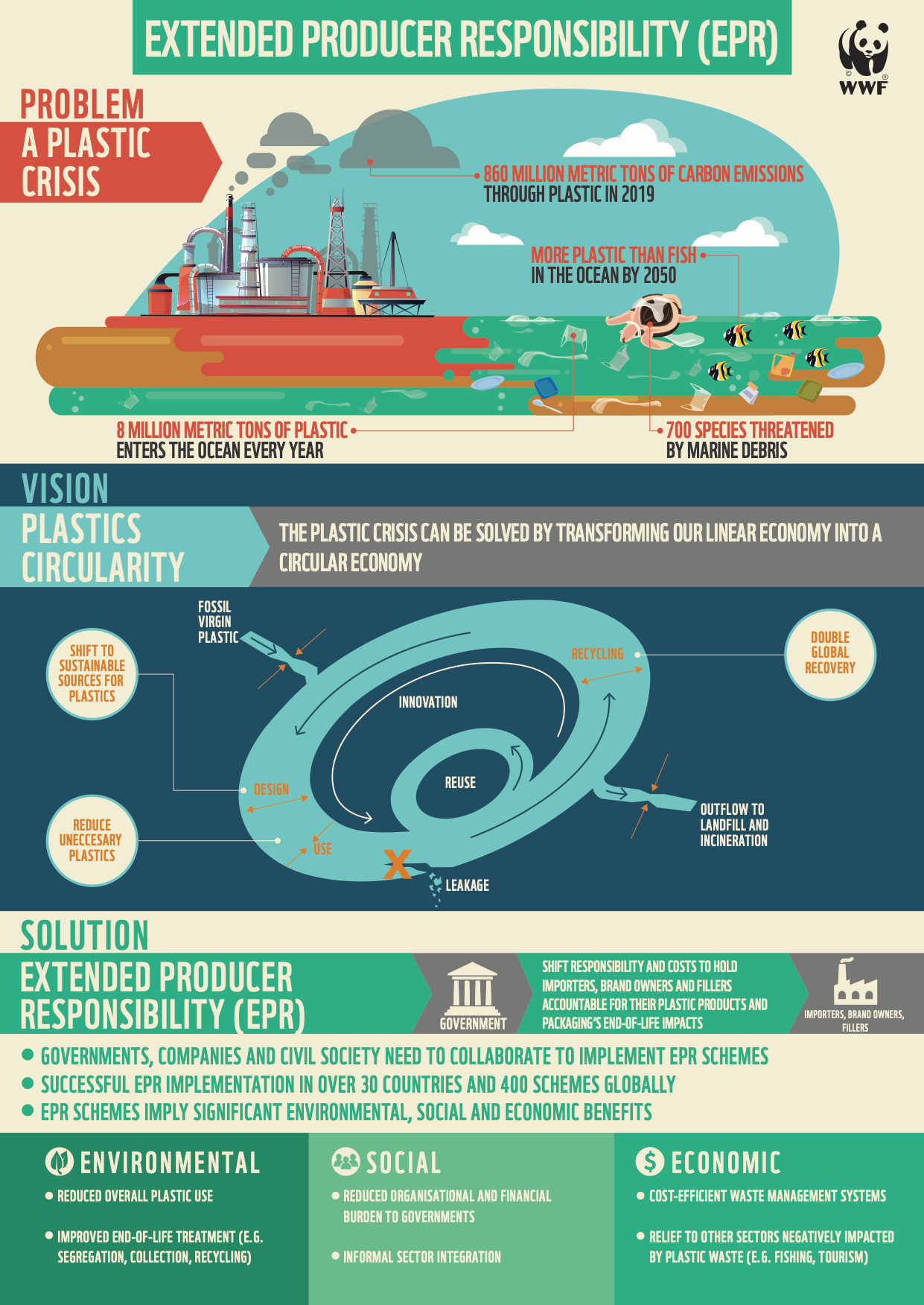

According to the United Nations, the Philippines is one of five countries from which plastic pollution originates before flowing to the rest of the world. To help address this, WWF along with Congress, are working on a legislation that shall compel producers, manufacturers and businesses to be accountable for the waste they put into the market. A scheme, here and abroad, called Extended Producers Responsibilty (EPR), shall bill them ahead for their plastic waste contribution to society. This is expected to encourage stakeholders to redesign their products with recyclability or reusability in mind to avoid exorbitant EPR fees. One of the first effects expected out of EPR is the innovation of eco-friendly plastic products. Other than RA 9003, otherwise known as the Philippine Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000, this is by far one of the most aggressive steps taken towards arresting the catastrophic effects of non-recyclable plastics in our environment.

The plastic crisis and the Expanded Producer Responsibility promotes accountability and collaborative efforts solution. © WWF Philippines

The plastic crisis and the Expanded Producer Responsibility promotes accountability and collaborative efforts solution. © WWF Philippines

Paper or plastic?

It is not enough to opt for paper bags while shopping. This practice potentially harms virgin forests, while reusable bags require 131 uses to qualify them as sustainable. Waste management remains an ideal option—which, unfortunately, local governments find difficult to finance. Constantino relates, “Most recycling facilities WWF has worked with are privately owned. It is also a fact that most machines that local governments own are for composting, and not recycling.”

Though the lack of recycling facilities and accessible recycling programs add to the ongoing plastic crisis, there is simply an overwhelming amount of plastic wastes, which spill out to nature and contribute to flooding issues. In this light, Constantino stresses the importance of household waste management system. “Start with ourselves. Apart from changing yourself, you also have to change the system. Practice segregation. Apart from changing your lifestyle, you have to change the system so you can influence. People can influence systemic changes in their areas.”

Plastic use in the time of pandemic

A recent study conducted in July 2020 by Pew Trusts indicates that at present, 11 million metric tons of plastics enter the oceans annually, which can possibly triple by 2040. Still, Constantino acknowledges there are necessary plastics. “We do not say that let us eliminate all plastics. For WWF, there are necessary plastics. We usually relate them to food safety and health security. If it’s something that would help decrease the food wastes, we’re okay with that.”

However, this projection has not taken into account the pandemic effect on the usage of plastics brought about by food consumption and health security. In the Philippines, our waste management solution is mostly through landfills shared by cities. Presently, the WWF has not received confirmation on whether the lifespan of these landfills will be greatly affected by the increase in plastic consumption these last few months.

Microwavable plastic containers collected in one month by a household of 4 in May 2020. © River Rosal

Microwavable plastic containers collected in one month by a household of 4 in May 2020. © River Rosal

WWF expects the numbers to rise as a consequence. “While we were conversing with Manila City, ang next nilang problem, mapupuno na raw yung landfill by 2026,” Constantino shares. “That’s pre-COVID, pero ngayon hindi ko alam kung that is still the projection. Recently, there’s really a significant increase of plastic use—lalo na yung mga tao, stay at home, padeliver lahat. Some businesses, dati pwede ka magdala ng resuables, pero ngayon, kinansel muna nila due to health reason daw. Kasi parang nag-shift din yung mga businesses, na dating nag-re-reusables, or dating nag-e-entertain ng reusability, ngayon, parang stop muna natin.’” (While we were conversing with the Manila City government, they shared that their next problem is that the landfill could be filled to capacity by 2026. That’s pre-COVID, but now, I don’t know if that is still the projection. Recently, there has been a significant increase of plastic use. Because people are at home, everything gets delivered. Some businesses used to allow reusables, but these days, that option is cancelled, supposedly due to health reasons. There appears to be a shift among businesses who used to accommodate reusables, or those who used to entertain reusability. But now they’re saying, “Let’s stop for a while.”)

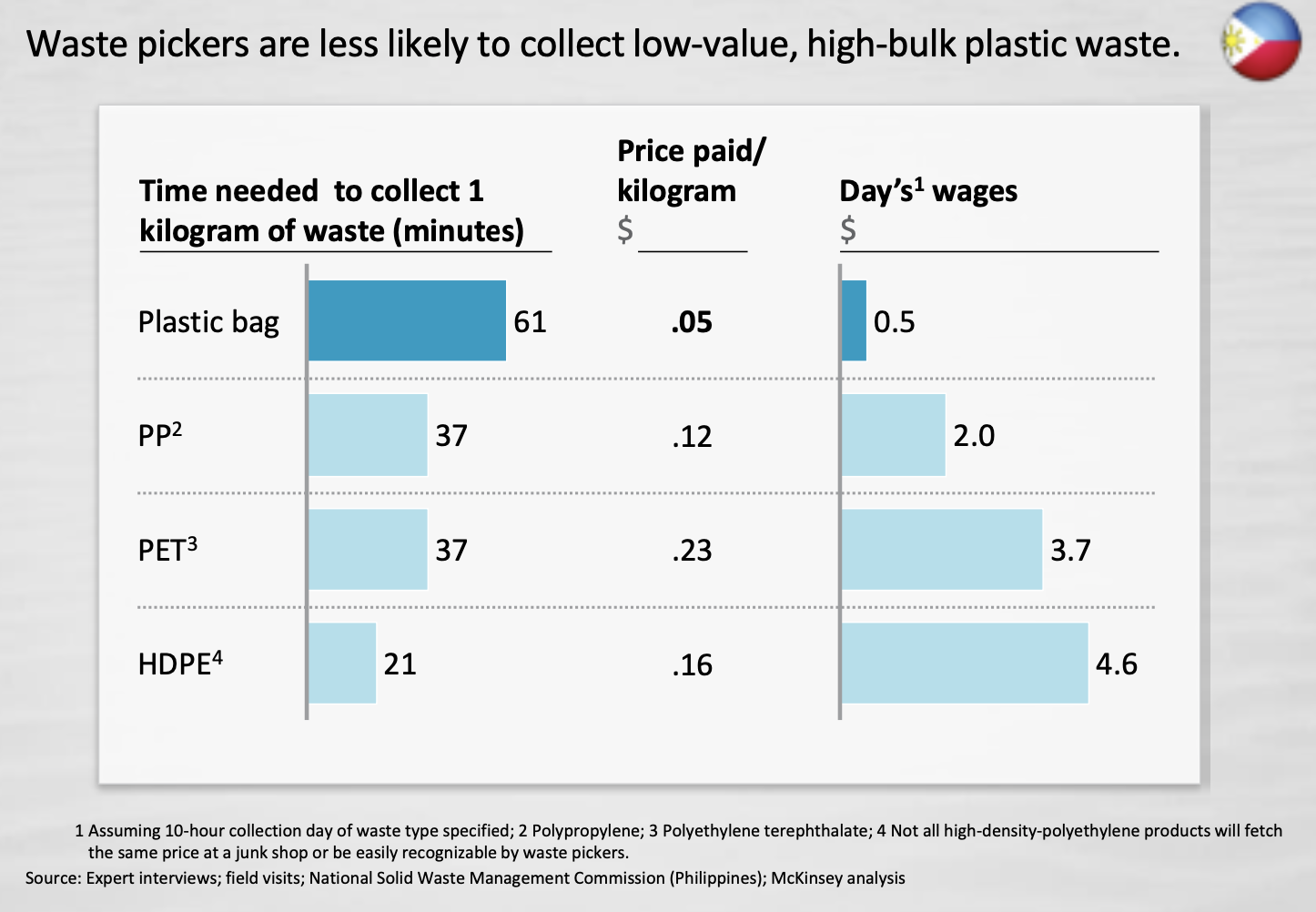

High-value plastic such as PET and HDPE are not prioritized by waste pickers in the Philippines. © McKinsey Center for Business and Environment

High-value plastic such as PET and HDPE are not prioritized by waste pickers in the Philippines. © McKinsey Center for Business and Environment

Reduce, reuse and recycle

There is only good in knowing these numbers however alarming they may be, because what cannot be measured, cannot be managed. With data, plastic reduction plans can be mapped out— refusing plastic, reusing what we acquire, and adapting recycling plans at home and in the community. The system has to go beyond the home. If we can only manage to retrieve those and recycle them, we can help manage the plastic crisis.

In the Philippines, studies show that while 62.6% account for the non-recyclable plastics including the single-use plastic packaging and sachets, the remaining percentage (37.4%) of plastic wastes consist of high value plastics such as PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottles and HDPE (high density polyethylene) containers like shampoo and other toiletries containers, plastic jugs for juices and sauces to name a few. These are all highly recyclable and yet end up in landfills because of two possible reasons: lack of recycling capability, and the lack of awareness among communities and households on waste segregation.

In order for Filipinos to successfully reduce, reuse, and recycle, the end points of plastic waste disposal must be always secured. There are various organizations that can help. For example, Green Antz Builders has drop-off hubs for discarded sachets and other clean and dry plastic wastes. They incorporate about 100 sachets in cement mix to make eco-bricks. Papelmeroti accepts discarded bubble wrap and other plastic wastes. The Plastic Solution collects and repurposes PET bottles to create wall fillers.

Fully packed PET bottles turned into bricks for wall partitions ( The Plastic Solution. ©2020.)

Fully packed PET bottles turned into bricks for wall partitions ( The Plastic Solution. ©2020.)

Communities can also initiate recovery projects with local government units for the segregated collection of plastic wastes to turn them into cash, or to mobilize junk shop projects. Constantino shares that as of last inquiry, the PET bottles are worth P5.00 per kilo, while P17.00 per kilo is the going rate for plastic bottle caps. The Department of Trade and Industry has also created an income forecast for communities, such as condo complexes, to start their own plastic collection and junk shops.

If the nation can recover the 37.4% of high-value plastics and recycle them, the plastic crisis in the Philippines can slowly be mitigated. If single-use plastics are refused, while others are reused and recycled, manufacturers will eventually redesign their products to adapt to the discerning, environmentally-aware public.