Latest data from the Department of Health (DOH) stated that at least 2.6 million Filipinos have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19. According to herdimmunity.ph, this is only 3.76% of the 70-million population the government aims to vaccinate this year to achieve herd immunity. The website says that at the current average rate of 216,451 daily vaccinations, herd immunity will be reached in 1.6 years, or in February 2023. For us to achieve herd immunity by the end of the year, the government needs to ramp up its vaccination 3.3 times its current rate.

Herd immunity or population immunity is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the “indirect protection from an infectious disease that happens when a population is immune either through vaccination or immunity developed through previous infection.” To better understand how we can reach this goal faster, the pilot online episode of Panayam sa Panahon TV featured the experts—health reform advocate Dr. Anthony Leachon and Dr. Noel Bernardo from the Philippine Red Cross.

(photo from Quezon City Hall’s Facebook page)

(photo from Quezon City Hall’s Facebook page)

Why PH is falling behind in the global vaccination drive

When the COVID-19 vaccines still weren’t available, governments resorted to lockdowns to stop the spread of disease. But now, countries like the United Kingdom and the United States have freed up their economies, thanks to systematic and rapid vaccination programs. In a recent segment of Panahon TV called Buhay Pandemya, which featured a Filipino caregiver in Jerusalem in Israel, maskless locals can be seen flocking to the streets and celebrating the return of normalcy. Israel was one of the countries that started their vaccination early, which began last December 2020.

But the scenario in the Philippines is a different story. Though cases in the National Capitol Region (NCR) have been somewhat contained, other areas are experiencing surges. Lockdowns and quarantines are still in place, keeping the economy from fully recovering. If we already know the tried-and-tested formula of mass vaccination as the main key to herd immunity, why then are we still behind in the immunization drive? Our experts chalked it up to three main reasons.

- Lack of vaccine supply

Based on Our World in Data’s latest report, the Philippines ranks 8th among the 10 ASEAN countries in terms of vaccine rollout. During the interview, Dr. Bernardo expressed surprise over his discovery that out of the 3,700 approved vaccination sites in the country, only 1,700 are active. “Based on my experience on the ground with the different LGUs and the bakuna centers of the Philippine Red Cross, a big factor is the lack of vaccines,” he said in Filipino. “Bakuna centers don’t receive enough vaccines. Other LGUs (local government units) can only operate half-days.” Dr. Leachon was quick to agree. “If you don’t have vaccines, it doesn’t matter if you have vaccination sites. People will still have no access to vaccination.”

- Lack of organization

With data gathered from DOH, the National Task Force Against COVID-19, the Inter-Agency Task Force and news outlets, Herdimmunity.ph states that we currently have over 17 million vaccine doses, “enough to fully vaccinate 12.47% of the target population.” If such is the case, why is the vaccination still slow?

Dr. Leachon pointed out that LGUs have varying levels of governance, with some more organized than the others. Because best practices are not adopted by all LGUs, they also have varying levels of success, making it harder for the country to reach herd immunity.

Meanwhile, Dr. Bernardo said that we should attack the issue with a “system approach”. He cited how a simple step such as securing a vaccination schedule has become problematic. “People shouldn’t have to walk in like chance passengers. When we schedule them, we know that number one, they fully consent to the vaccination. Second, they should know their vaccine brand so they can manage their expectations. That way, we avoid overcrowding. Third, our supply should cope with our demand. If people leave the site disappointed because of the hassle or lack of vaccine, then they will recount their bad experience to others. But if their experience is positive, others will be motivated to be vaccinated.”

In January this year, a Pulse Asia Survey resulted in 4 out of 10 Filipinos not wanting to get vaccinated. According to Bernardo, the survey was repeated in March. This time, the figure climbed up to 6 out of 10 Filipinos refusing vaccination. “There must be something about the people’s experience in the bakuna centers that increased hesitancy—which we must address right away. Because even if the government promised a flood of vaccines eventually coming in, will people agree to be vaccinated?”

- Vaccine Hesitancy

According to DOH, 9% or over 100,000 of vaccinees who received their first dose missed out on their second dose. According to Dr. Leachon, apart from disorderly systems that discouraged Filipinos, this may be also attributed to the lack of information, leading to decreased awareness. “Maybe they don’t know where they will go to for their second dose. Different vaccine brands have different durations between the two doses. Vaccinees should be given a checklist that includes all the info they need, including when they should return.”

Leachon also suggested massive info campaigns on the possible adverse effects of the vaccine, and the mode of registration. “Online registration is very difficult for the elderly and the poor. Why should we make it hard for them? We need to have a faster registration process.” Another common complaint among registrants is the slow response of LGUs.

Recently, the issue of vaccine brands became even more heated when hundreds of Indonesian health workers became infected with COVID-19 after being fully vaccinated with Sinovac. Recently, 10 Indonesian doctors died despite their complete inoculation with the Chinese vaccine. Until now, China has not provided large-scale data on Sinovac’s effectiveness against the Delta variant. “Our life is all about choices,” Dr. Leachon said. “We choose our spouse, clothes, food. So, it’s even more important to choose what is injected into our bodies. When we don’t give people choices, we’ll have a hard time convincing them to get vaccinated.”

According to WHO, the Sinovac vaccine, in a phase 3 trial in Brazil “showed that two doses, administered at an interval of 14 days, had an efficacy of 51% against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection.” With vaccine brands such as Pfizer and Moderna having an efficacy of 90% or more, some Filipinos are thinking twice about being inoculated with Sinovac. “About 70% of our vaccine inventory is Sinovac. What we’ve seen in Parañaque and Manila wherein residents flocked to the vaccination sites that gave out Pfizer is a sign that Filipinos are brand-conscious. They know their health is on the line. They value the quality, efficacy and safety of the vaccine,” Leachon said.

“Bakuna bus”—a partnership of the Philippine Red Cross and UBE Express

“Bakuna bus”—a partnership of the Philippine Red Cross and UBE Express

Ways to improve the vaccination drive

Once the main issue of vaccine supply is addressed, our interviewees suggested the following to ramp up our vaccination drive:

- Prioritize urban areas that drive the national economy.

ABS-CBN Data Analytics Head Edson Guido recently tweeted that though COVID-19 cases in NCR are decreasing, only 7.4% of its population are fully vaccinated. Dr. Leachon suggested that prioritizing the NCR Plus Bubble can help the country achieve herd immunity faster. “We shouldn’t spread the vaccine supply thinly across the country, especially those with no cold-chain facilities. For example, we’re expecting 40 million doses of Pfizer, which will fully vaccinate 20 million people. It’s better to prioritize super metro areas like NCR Plus, which has a population of around 26 million—and 70% of that is 18 million. If herd immunity is achieved in NCR Plus, we can open our economy in time for December 2021.”

- Make vaccines more accessible.

Although mega vaccination sites may work, Dr. Leachon pointed out that these are available only in selected areas. He believes that small but multiple vaccination sites may be more efficient. “Mega vaccination sites are prone to bottlenecks and may be superspreading events. Vaccination sites should be convenient for the elderly and those with comorbidities. These sites should be many and close to residents, who can be vaccinated faster because they don’t have to worry about transportation. Because the crowd is spread out among multiple sites, waiting time is reduced.” Dr. Leachon suggested taking inspiration from successful countries, which mobilized malls, drugstores and other convenient stores which have cold-chain infrastructure in the vaccination drive.

Dr. Bernardo agreed that the solution lies in community-based vaccination sites. “We really have to bring the vaccine closer to our people, so they will be encouraged. If every barangay has a mini-vaccination site which can only accommodate 20 people a day, that can already make a big difference.” He also enjoined the government to give vaccination leaves for employees. “In bakuna centers I’ve visited, I asked those who weren’t able to get their second dose what happened. They told me it’s because they couldn’t file a leave. We have to consider living factors like this.”

To help more Filipinos be vaccinated, Red Cross Philippines has partnered with UBE Express in employing mobile vaccination buses to reach far-flung areas that do not have cold-chain facilities. “We are ready to partner with national agencies, LGUs, NGOs and private sectors to maximize this initiative and utilize all the logistical support that Red Cross could offer. When the vaccines arrive, we will go to places not accessible to health workers and NGOs.”

- Strengthen governance.

One important aspect of good governance, especially in our country, is disaster preparedness. Currently, we are in the middle of the rainy season, which may pose challenges in the vaccination drive. “First, vaccination programs are usually done in open courts, gyms and other large open spaces, which have good ventilation. But when it rains, these outdoor areas will be affected,” Dr. Leachon explained. “Second, you need to separate evacuation centers for typhoon victims, isolation and quarantine facilities, and vaccination sites. Because the moment people from these areas mix, this can be super-spreading event.” Another concern is power outages that may affect cold-chain facilities.

Government responsiveness is also important in gaining public trust and cooperation. “For example, we know that the reason why the cases are not going down is because we lack contact tracing. But the governments don’t respond to this. The same way with surveys done by SWS and DOH, which showed the participants’ preferred vaccine brands and their perceived effects. You have to execute a program based on what the citizens want, or else you will be doing the same thing all over again, but expecting a different result,” said Dr. Leachon.

Marmick Julian, a proud vaccinee in Parañaque, displays his injected arm. (photo by Robi Robles)

Marmick Julian, a proud vaccinee in Parañaque, displays his injected arm. (photo by Robi Robles)

Achieving herd immunity

Dr. Bernardo believes that promoting vaccine confidence is an important step toward herd immunity. “The first vaccine brand we received should’ve been the best and most trusted. But a lot of doubts and issues were involved in our first vaccine—which was one of the main reasons of vaccine hesitancy.” To promote vaccine confidence, Dr. Bernardo stressed the need for better communicators. “There was a comms group that suggested that we relate vaccination to family. When you get yourself vaccinated, it’s a sign of love for your family and friends.”

As to achieving herd immunity this year, Dr. Bernardo was skeptical but hopeful. “We need 500,000 vaccinations a day if we want to have a happy Christmas this year.” Meanwhile, Dr. Leachon still emphasized the importance of vaccine efficacy. “We can only achieve herd immunity when the vaccines from Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca arrive. We need to step up to the plate in the next 3 months and revisit our strategies,” he ended.

Watch Panayam sa Panahon TV’s Herd Immunity: Kailan at Paano Natin Ito Maaabot?

- What is coronavirus?

The coronavirus is a type of virus that causes respiratory illness in animals and humans. It is zoonotic, meaning it can be transmitted between animals and humans. The virus was first discovered during the 1960s, and was called coronavirus because of its crown-shaped structure.

As of now, there are seven types of the coronavirus that can infect humans. They range from the common cold to more severe diseases, such as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV), and its latest strain, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).

MERS-CoV, discovered in Saudi Arabia last 2012, resulted in 858 deaths. According to scientists, this coronavirus came from camels and has flu-like symptoms. Meanwhile, SARS began in China in 2002. It was reported to have come from a civet cat, and has 8,000 confirmed cases, killing almost 800.

On January 9, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a new strain of coronavirus, associated with an outbreak of pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Last February 11, 2020 it was renamed as the Coronavirus Disease-2019 COVID-19.

- Is COVID-19 deadly?

Just like MERS-CoV and SARS, the COVID-19 is deadly. The moment one gets infected, the virus spreads immediately to the lower respiratory tract, including the lungs. This type of coronavirus may cause severe pneumonia in 24 hours, and it cannot be cured by antibiotics.

- What are the symptoms of COVID-19?

Its respiratory symptoms include fever, cough, shortness of breath and other breathing difficulties. However, there are cases of the coronavirus disease that are asymptomatic or display no symptoms. It takes around 14 days before the symptoms appear.

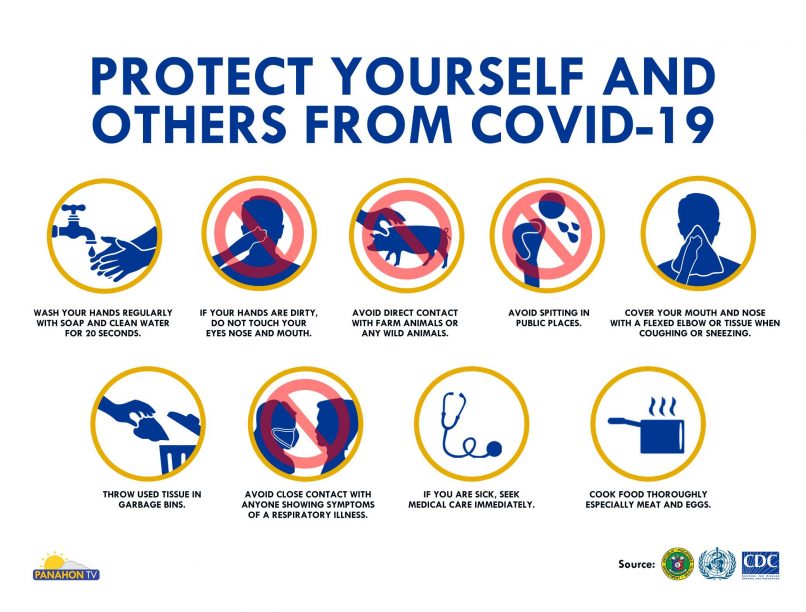

- How can you protect yourself from this virus?

According to the World Health Organization, here are the ways to prevent yourself and others from getting the COVID-19:

- Wash your hands regularly with soap and clean water for 20 seconds.

- If your hands are dirty, do not touch your eyes nose and mouth.

- Avoid direct contact with farm animals or any wild animals.

- Avoid spitting in public places.

- Cover your mouth and nose with a flexed elbow or tissue when coughing or sneezing.

- Throw used tissue in garbage bins.

- Avoid close contact with anyone showing symptoms of a respiratory illness.

- If you are sick, seek medical care immediately.

- Cook food thoroughly especially meat and eggs.

- What should you do if you have a scheduled travel abroad?

- If you are sick, avoid traveling.

- If you’re sick, seek medical care immediately and share your recent travel history.

- If you are wearing a face mask, make sure to cover mouth and nose. Avoid touching mask once it’s worn.

- Discard the single-use mask after each use and wash hands immediately.

- Avoid close contact and travel with sick animals.

- Make sure to eat well-cooked food.

- How can you cope if you’re stuck abroad and can’t go home?

- Keep in touch with your family.

- Maintain healthy lifestyle, including proper diet, sleep and exercise.

- Don’t believe everything that’s posted on social media. Get the facts. Always check reliable sources of information about this disease.

If you need more information, please check these sources:

- Department of Health – https://www.doh.gov.ph/

- World Health Organization – https://www.who.int/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/