Plastic-wrapped nation. Illustrated by sticker artist Zahnina Jayne Rosal ©2020

Nearly everything we use in our daily lives is made of plastic. We start the day by using a plastic toothbrush. To save money, we pack meals in a plastic container. On the way to the office, we pick up coffee in a disposable cup, which sometimes comes with disposable plastic straw. At the office, we attend a meeting that serves water, juice, or soda in PET bottles.

These modern conveniences seem harmless but in abundance, compounded by habitual improper waste disposal, is how the world has found itself nearly suffocated in plastic.

Single-use plastic is everywhere

According to a United Nations environmental report, “Our planet is drowning in plastic pollution. Around the world, one million plastic drinking bottles are purchased every minute, while up to 5 trillion single-use plastic bags are used worldwide every year.” Half of these plastics are manufactured as single-use products, eventually discarded to contribute to the 300 million tonnes of plastic waste and debris the world produces annually.

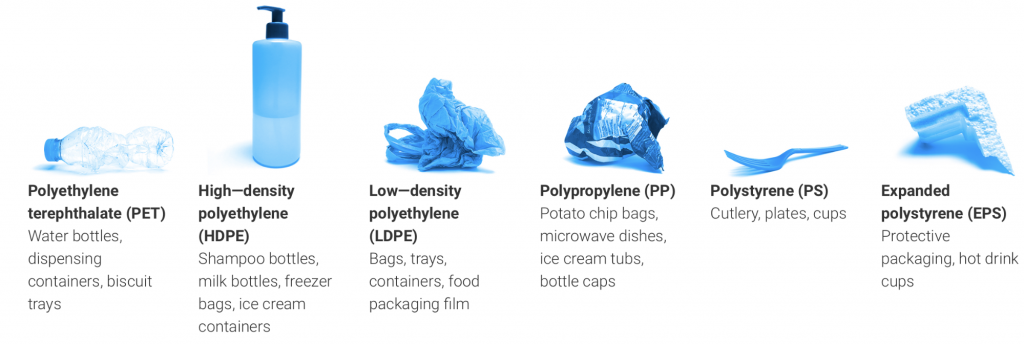

Different types of plastics (grabbed from UN Environment Report)

Different types of plastics (grabbed from UN Environment Report)

These plastic pollutants degrade into smaller fragments—from undetectable microplastic (>5mm) about the size of sesame seeds, to macroplastic (<5mm) large enough to be easily recognized in its original form. These find their way into catchments before being discharged to rivers, seas, beaches, and recently, even in remote, pristine locations like Lake Geneva in Switzerland and Lake Guarda in Italy.

The world is so littered with plastic that a recent study has indicated the presence of small pieces of plastic waste even in the remote mountain ranges of the French Pyrenees. Samples found from the mountains include microplastics likely from single-use plastic packaging from take-out food and PET bottles transported through the air.

The throw-away culture and soft plastics

In the Philippines, soft plastics are the most prevalent plastic litter found in our waters, according to Amy Slack, an environmental consultant who regularly volunteers for Marine Conservation Philippines to work with international movement Break Free From Plastic in Negros Oriental initiative. In her analysis of plastic waste collected during their group’s beach cleans in December 2019, she blogged: “Consistently, the vast majority of the debris we found strewn across the beaches across the Philippines was plastic; a significant amount of that was soft plastics which can’t be recycled – plastic bags, sweet and crisp packets, and single-use soap and detergent sachets. There were some variations though: at one beach, we kept picking up a staggering amount of styrofoam.”

Sachets are non-recyclable multilayered, single-used plastic. © Amy Slack

Sachets are non-recyclable multilayered, single-used plastic. © Amy Slack

Recycling facility in Quezon City, taken during a field visit last February 2020. © Czarina Constantino / WWF-Philippines

Recycling facility in Quezon City, taken during a field visit last February 2020. © Czarina Constantino / WWF-Philippines

Though their organization was able to fish out trash and segregate, another road block cropped up. According to Slack, “It became increasingly apparent that part of the problem was the variability of waste management across the municipality of Zamboanguita, in the Negros Oriental province.” Aside from the lack of resources or end-points, many locals have no recycling knowledge at all. This seems to be the case not only in the municipality of Zamboangita, Negros Oriental, but also around the country.

Meanwhile, Czarina Constantino of World Wide Fund for Nature Philippines (WWF), also the national lead for “No Plastics in Nature” Initiative acknowledges this. “Meron ‘pag Luzon, pero ‘pag mga Visayas or Mindanao, Hirap sila. Kasi archipelagic pa rin tayo. Sobrang hirap rin para kulektahin ang mga basura. Sobrang gastos. (There are in Luzon, but they’re scarce in Visayas and Mindanao because our country is archipelagic. It is very challenging to collect garbage. It’s very expensive.)

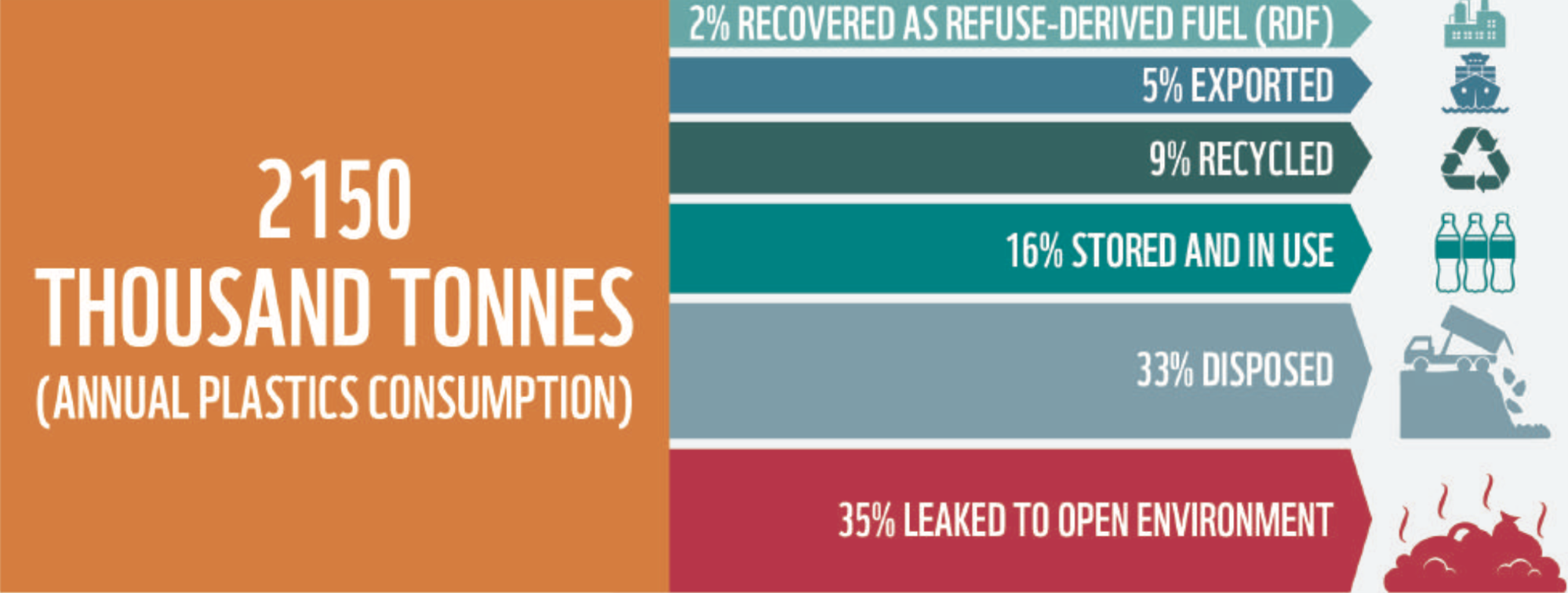

The number of recycling facilities in the country is too limited to accommodate all the plastic waste the country generates, which is about 20 kilograms per person annually, or 2,150,000 tons of plastic waste in 2019, according to the 2020 WWF findings from its recently conducted material flow analysis of plastic packaging waste.

Flow of Plastic Materials in the Philippines in 2019 © WWF Philippines

Flow of Plastic Materials in the Philippines in 2019 © WWF Philippines

Sachets, Extended Producers Responsibility and eco-design

Sachets are made of several layers of different types of plastic, which require separation prior to recycling. Some of these layers have very poor recyclability, and with all the mechanical steps required to separate them, it is neither economical nor profitable to recycle sachets. It is decidedly a single-use product, and a good number of case studies suggests it to be the likely culprit to our environment’s plastic woes.

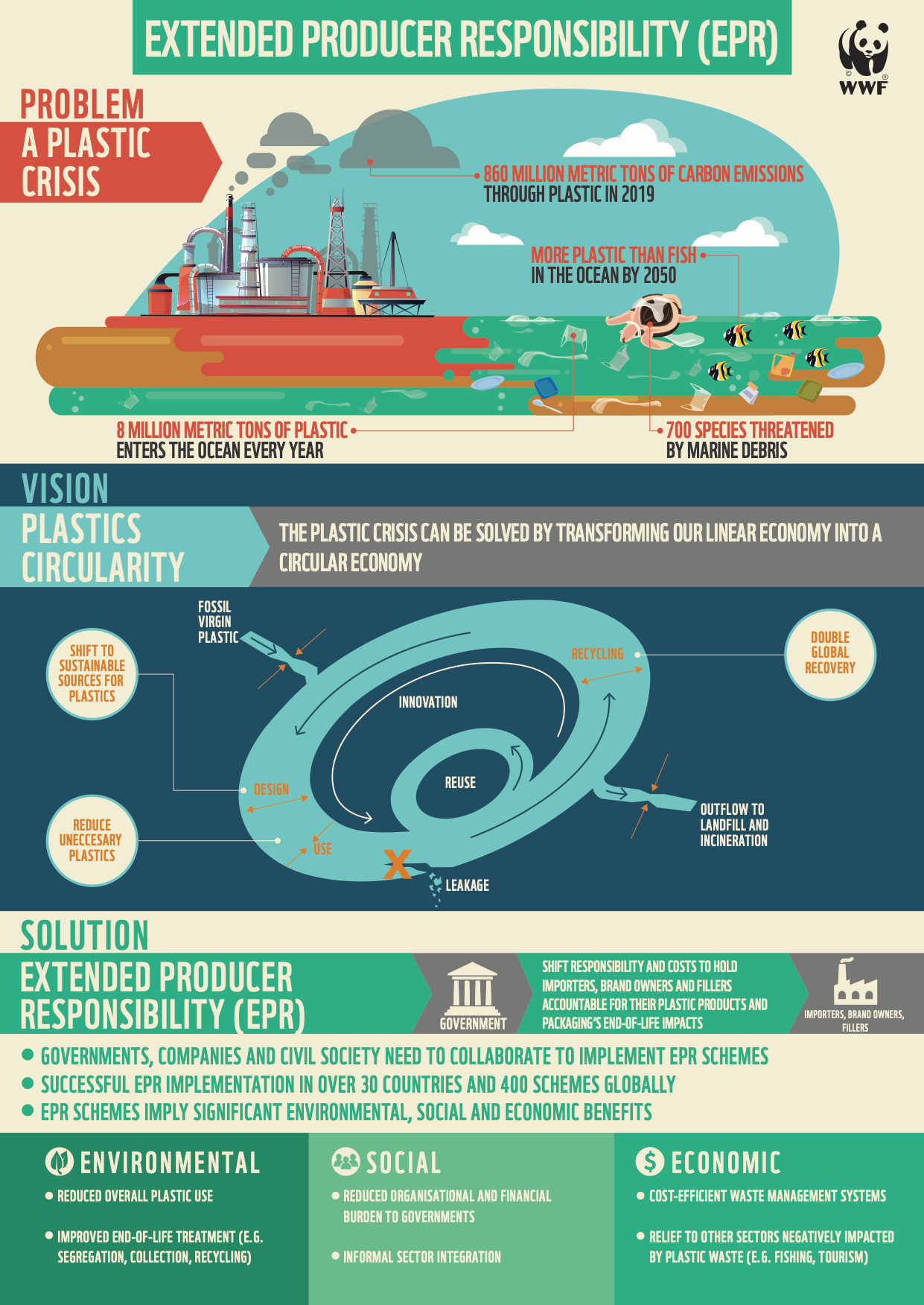

According to the United Nations, the Philippines is one of five countries from which plastic pollution originates before flowing to the rest of the world. To help address this, WWF along with Congress, are working on a legislation that shall compel producers, manufacturers and businesses to be accountable for the waste they put into the market. A scheme, here and abroad, called Extended Producers Responsibilty (EPR), shall bill them ahead for their plastic waste contribution to society. This is expected to encourage stakeholders to redesign their products with recyclability or reusability in mind to avoid exorbitant EPR fees. One of the first effects expected out of EPR is the innovation of eco-friendly plastic products. Other than RA 9003, otherwise known as the Philippine Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000, this is by far one of the most aggressive steps taken towards arresting the catastrophic effects of non-recyclable plastics in our environment.

The plastic crisis and the Expanded Producer Responsibility promotes accountability and collaborative efforts solution. © WWF Philippines

The plastic crisis and the Expanded Producer Responsibility promotes accountability and collaborative efforts solution. © WWF Philippines

Paper or plastic?

It is not enough to opt for paper bags while shopping. This practice potentially harms virgin forests, while reusable bags require 131 uses to qualify them as sustainable. Waste management remains an ideal option—which, unfortunately, local governments find difficult to finance. Constantino relates, “Most recycling facilities WWF has worked with are privately owned. It is also a fact that most machines that local governments own are for composting, and not recycling.”

Though the lack of recycling facilities and accessible recycling programs add to the ongoing plastic crisis, there is simply an overwhelming amount of plastic wastes, which spill out to nature and contribute to flooding issues. In this light, Constantino stresses the importance of household waste management system. “Start with ourselves. Apart from changing yourself, you also have to change the system. Practice segregation. Apart from changing your lifestyle, you have to change the system so you can influence. People can influence systemic changes in their areas.”

Plastic use in the time of pandemic

A recent study conducted in July 2020 by Pew Trusts indicates that at present, 11 million metric tons of plastics enter the oceans annually, which can possibly triple by 2040. Still, Constantino acknowledges there are necessary plastics. “We do not say that let us eliminate all plastics. For WWF, there are necessary plastics. We usually relate them to food safety and health security. If it’s something that would help decrease the food wastes, we’re okay with that.”

However, this projection has not taken into account the pandemic effect on the usage of plastics brought about by food consumption and health security. In the Philippines, our waste management solution is mostly through landfills shared by cities. Presently, the WWF has not received confirmation on whether the lifespan of these landfills will be greatly affected by the increase in plastic consumption these last few months.

Microwavable plastic containers collected in one month by a household of 4 in May 2020. © River Rosal

Microwavable plastic containers collected in one month by a household of 4 in May 2020. © River Rosal

WWF expects the numbers to rise as a consequence. “While we were conversing with Manila City, ang next nilang problem, mapupuno na raw yung landfill by 2026,” Constantino shares. “That’s pre-COVID, pero ngayon hindi ko alam kung that is still the projection. Recently, there’s really a significant increase of plastic use—lalo na yung mga tao, stay at home, padeliver lahat. Some businesses, dati pwede ka magdala ng resuables, pero ngayon, kinansel muna nila due to health reason daw. Kasi parang nag-shift din yung mga businesses, na dating nag-re-reusables, or dating nag-e-entertain ng reusability, ngayon, parang stop muna natin.’” (While we were conversing with the Manila City government, they shared that their next problem is that the landfill could be filled to capacity by 2026. That’s pre-COVID, but now, I don’t know if that is still the projection. Recently, there has been a significant increase of plastic use. Because people are at home, everything gets delivered. Some businesses used to allow reusables, but these days, that option is cancelled, supposedly due to health reasons. There appears to be a shift among businesses who used to accommodate reusables, or those who used to entertain reusability. But now they’re saying, “Let’s stop for a while.”)

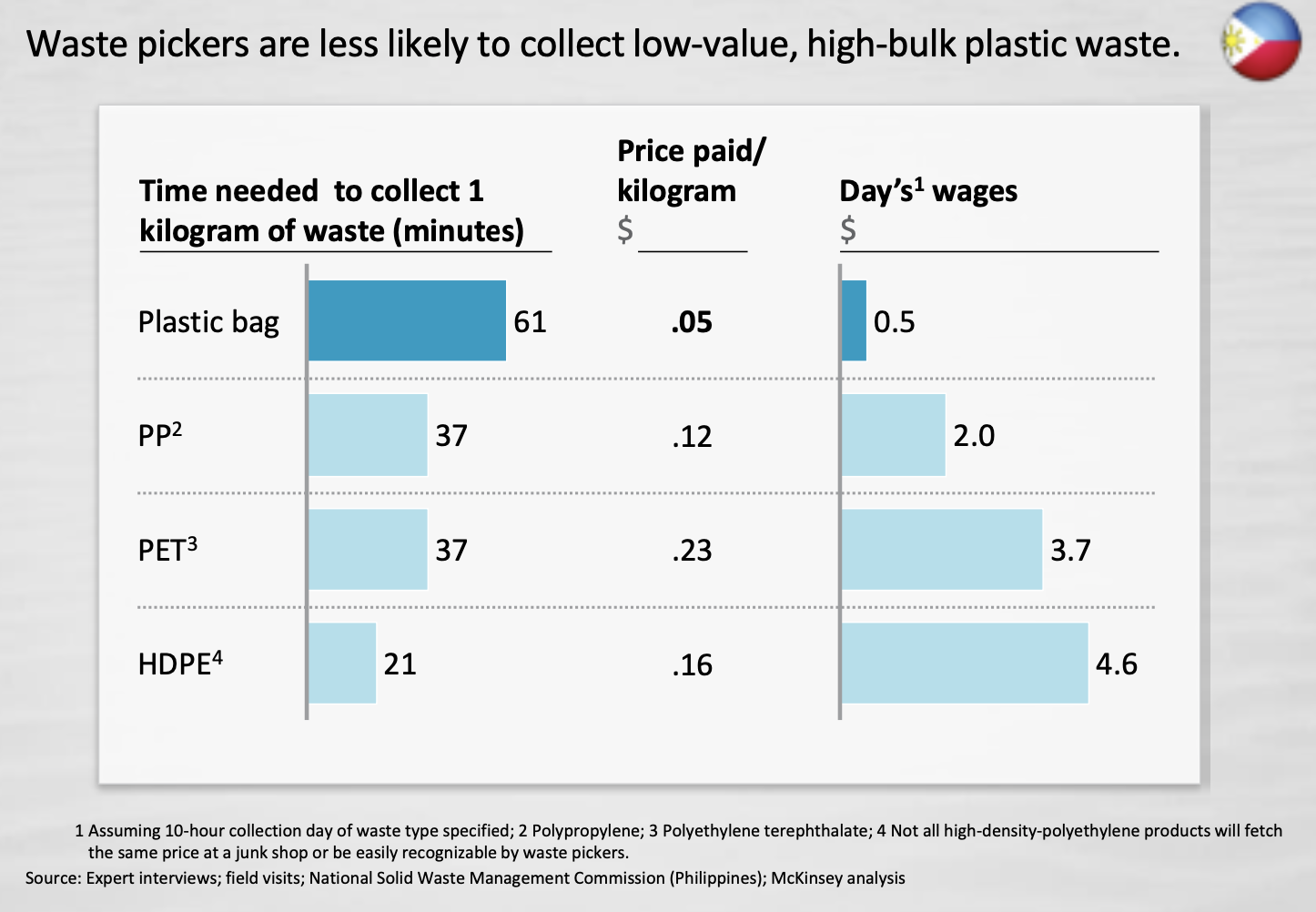

High-value plastic such as PET and HDPE are not prioritized by waste pickers in the Philippines. © McKinsey Center for Business and Environment

High-value plastic such as PET and HDPE are not prioritized by waste pickers in the Philippines. © McKinsey Center for Business and Environment

Reduce, reuse and recycle

There is only good in knowing these numbers however alarming they may be, because what cannot be measured, cannot be managed. With data, plastic reduction plans can be mapped out— refusing plastic, reusing what we acquire, and adapting recycling plans at home and in the community. The system has to go beyond the home. If we can only manage to retrieve those and recycle them, we can help manage the plastic crisis.

In the Philippines, studies show that while 62.6% account for the non-recyclable plastics including the single-use plastic packaging and sachets, the remaining percentage (37.4%) of plastic wastes consist of high value plastics such as PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottles and HDPE (high density polyethylene) containers like shampoo and other toiletries containers, plastic jugs for juices and sauces to name a few. These are all highly recyclable and yet end up in landfills because of two possible reasons: lack of recycling capability, and the lack of awareness among communities and households on waste segregation.

In order for Filipinos to successfully reduce, reuse, and recycle, the end points of plastic waste disposal must be always secured. There are various organizations that can help. For example, Green Antz Builders has drop-off hubs for discarded sachets and other clean and dry plastic wastes. They incorporate about 100 sachets in cement mix to make eco-bricks. Papelmeroti accepts discarded bubble wrap and other plastic wastes. The Plastic Solution collects and repurposes PET bottles to create wall fillers.

Fully packed PET bottles turned into bricks for wall partitions ( The Plastic Solution. ©2020.)

Fully packed PET bottles turned into bricks for wall partitions ( The Plastic Solution. ©2020.)

Communities can also initiate recovery projects with local government units for the segregated collection of plastic wastes to turn them into cash, or to mobilize junk shop projects. Constantino shares that as of last inquiry, the PET bottles are worth P5.00 per kilo, while P17.00 per kilo is the going rate for plastic bottle caps. The Department of Trade and Industry has also created an income forecast for communities, such as condo complexes, to start their own plastic collection and junk shops.

If the nation can recover the 37.4% of high-value plastics and recycle them, the plastic crisis in the Philippines can slowly be mitigated. If single-use plastics are refused, while others are reused and recycled, manufacturers will eventually redesign their products to adapt to the discerning, environmentally-aware public.

As the country struggles against the pandemic, the solution to combat COVID-19 seems to be the use of plastic and other disposable materials. Jeepneys, tricycles, buses and trains use plastic dividers to promote physical distancing among passengers; and since August 15, The Department of Transportation has mandated the populace to wear—along with face masks—face shields, usually made from plastic, when taking public transportation. Adding to the plastic burden is the deluge of food take outs and merchandise deliveries, deemed the safer option than dining out or going to malls during the pandemic.

Inside a jeepney in Bulacan (photo by PM Caisip)

Inside a jeepney in Bulacan (photo by PM Caisip)

But the Philippines isn’t the only country boosting waste production. In Thailand, home deliveries account for the increase of plastic waste from 1,500 tons to 6,300 tons per day. Last February, China ramped up its daily face mask production to a staggering 116 million daily, resulting in hundreds of tons of used masks in public bins each day.

Hospitals are also generating more waste. According to the Asian Development Bank’s data last April, Metro Manila hospitals, which deal with more than half of the country’s COVID-19 cases, were estimated to produce 280 metric tons of medical waste each day. A similar number was reflected last March in Wuhan hospitals, which produced more than 240 tons of daily waste at the height of the outbreak, compared with 40 tons during ordinary times.

Garbage in Misamis Oriental (photo by Manman Dejeto/Greenpeace)

Garbage in Misamis Oriental (photo by Manman Dejeto/Greenpeace)

Plastic Pollution

The United Nations Environment Programme (UN Environment) states that even before the COVID-19 pandemic, a million plastic drinking bottles were purchased every minute across the globe. Each year, up to 5 trillion single-use plastic bags are used worldwide, while 8 million tonnes of the world’s plastic end up in the oceans.

Plastic is widely produced and used because they are durable and don’t break down. Ironically, these traits are also the reason why they’re harmful to us and the environment. According to the UN Environment, most plastic items in the oceans are broken down into tiny particles easily swallowed by marine animals—the same animals that humans eat. Plastic has also found its way into our tap water, increasing our risk for ingesting them. By clogging drainages, plastic facilitates breeding grounds for pests, which give rise to vector-borne diseases such as dengue and malaria.

Plastic in the Philippines

According to a 2015 report released by the Ocean Conservancy, the Philippines ranks third among the world’s top plastic polluters of oceans.

But efforts to address rampant plastic use has been shelved due to the pandemic. In fact, the Quezon City government is thinking of suspending its ordinance on banning single-use plastic and disposable materials. But Greenpeace Campaigner Marian Ledesma emphasizes that such move can greatly impact an already ailing environment and population. “Single-use plastic is not inherently safer than reusables as it will cause additional public health concerns once discarded,” she says. “As the government gradually allows businesses to reopen, reusable systems and single-use plastic bans must be implemented to ensure the protection of the environment, workers, and consumers.”

Garbage from South Korea dumped in Misamis Oriental (Photo by Manman Dejeto/Greenpeace)

Garbage from South Korea dumped in Misamis Oriental (Photo by Manman Dejeto/Greenpeace)

Compounding the nation’s plastic crisis is the illegal waste trade. Since China stopped its waste importation, Southeast Asia has received a deluge of toxic garbage from developed countries. In the last three years, the ASEAN region, notably Malaysia, Philippines and Thailand, saw an astounding 171% growth—equivalent to over 2 million tonnes—in plastic waste imports. Data from Greenpeace Southeast Asia shows that from 4,267 tons in 2017, plastic waste imports to the Philippines rose to 11,761 tons in 2018. Most of these came from Japan, the United States, Taiwan, Indonesia, and Hong Kong.

Last year, the government began shipping back the controversial Canadian garbage, which slipped into the country between 2013 and 2014. The shipments, labeled as recyclable materials, was, in fact, made up of 64% unrecyclable residuals.

But NGO groups such Ecowaste Coalition and Greenpeace Philippines believe that the uncovered shipments show only the tip of the iceberg of waste that actually enters the country. They have been calling for the government to sanction the Basel Ban Amendment, which bans the import of all waste, including those for recycling. “The ratification of the Basel Ban Amendment (BBA) and the enactment of a total ban on waste imports is crucial, especially at a time when the nation grapples with recovery from a global pandemic that has led to the proliferation of medical and household waste,” Greenpeace Country Director Lea Guerrero said. “Lack of prohibitions on waste imports and poor enforcement of existing regulations leave the country open to future incidents of illegal waste trade, which often results in recipient countries shouldering the health and environmental costs of foreign waste.”

Enterprising Pinoys, including Eli/sew/beth, are making and selling reusable face masks

Enterprising Pinoys, including Eli/sew/beth, are making and selling reusable face masks

Go for Reusable, Not Disposable

A study published in Environmental Science & Technology states that an estimated 129 billion disposable masks and 65 billion disposable gloves are used worldwide each month during the pandemic.

This concern has prompted over 130 global health experts—including scientists, academics, doctors, and authorities on public health and food packaging safety— to sign a statement that assures the public that reusables, when coupled with basic hygiene, are safe during the pandemic. In an interview with Greenpeace Philippines, Dr. Geminn Louis Apostol of the Ateneo School of Medicine and Public Health stated that the pandemic waste has led to widespread environmental contamination, as well as increased public health risk. “Inequitable access to PPE (personal protective equipment) and to information about how to stay safe has contributed to the disproportionate rates of infection in poor and minority communities. If medical masks are prioritized for healthcare workers, the general public can use cloth masks as a safe, cost-effective alternative.”

Though health and safety is a pressing issue during the pandemic, outbreaks have long been linked to environmental degradation. By lessening our waste during these challenging times, we also lessen our risk for sickness. As Dr. Renzo Guinto, a physician and public health expert on health, climate change, and the environment, stated in an interview, “Protecting the public’s health must include maintaining the cleanliness of our home, the Earth. We don’t need to choose one over the other – we can protect ourselves from COVID-19 while protecting the environment.”