Home > Blog > Environment

Teaching Kids to Care for the Environment the Write Way

Our country’s natural environment is in a dire state. According to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Philippines is highly vulnerable to climate change with its increased weather events, and rising sea level and temperatures. A study conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2018 revealed that the Philippines ranks third in deaths due to air pollution. The country also ranks third as a source of plastic pollution in the oceans according to a 2015 report by Ocean Conservancy.

Pro-environment speeches always talk about how we need to save the environment for the next generation. But to solidify this advocacy, we need the next generation to fight alongside us in the name of environmental protection. And one effective way to do this is through children’s books that nourish young minds in engaging ways.

According to the 2017 Readership Survey by the National Book Development Board, picture books and storybooks for children are the second most-read book genre among respondents. Among children and even young adults, over 72% read the said genre.

Building on these statistics, Panahon TV celebrates Buwan ng Wika this August by featuring writers with a heart for Mother Nature. Their children’s books written in Filipino capture the next generation’s imagination, while instilling in them a love for the environment.

Writers slash Eco-Warriors

Liwliwa Malabed

Liwliwa Malabed

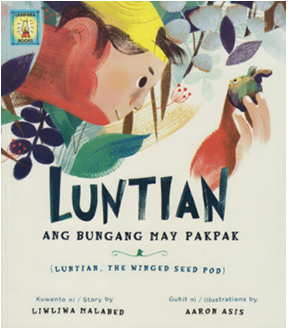

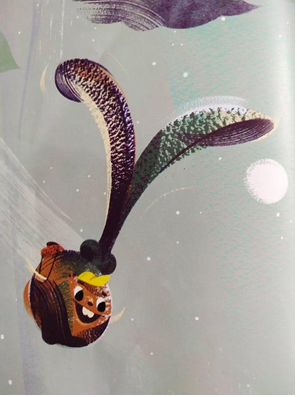

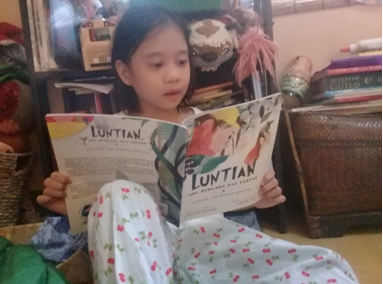

With 16 children’s books published and 4 more waiting in the wing, Liwliwa Malabed has been writing for young readers for 18 years. Some of her books have been recognized by the Philippine Board on Books for Young People through the PBBY-Salanga Writers’ Prize. We shine the spotlight on her environmental book Luntian, Ang Bungang May Pakpak (Luntian, the Winged Seed Pod), illustrated by Aaron Asis and published by Lampara Books. The story talks about Luntian, a seed pod who dreams of becoming a sturdy forest tree like her mother. While chasing his dream, Luntian goes on an adventure, meeting a Northern Luzon giant cloud rat and a Rafflesia, the world’s largest flower.

How did the concept for the book come about?

Luntian was written after a visit to the Makiling Center for Mountain Ecosystems (MCME) in Los Baños, Laguna. There, I saw towering native trees like the Red Lauan. Our guide told us about indigenous species that depend on these trees to survive. Somehow, the idea that one tree can support all these creatures stuck and I went back to Manila with the imprint of the lauan tree in my mind.

How did you craft the story?

First, I researched on dipterocarps. I learned about how their seeds have wing-like parts so they can ride the wind and reach far. I also looked up the animals and plants that live on these trees. I personified my characters because I needed the seed pod to come alive, to have an active role its story. It is still a seed, yes— but with an impatient desire to become a giant.

What do you think are your book’s strongest points?

I made a conscious decision to write it in Filipino and I am glad I did. A story resonates more with children when told in a language they can easily understand. I am also happy with the story within the story part of the book, that Luntian wants to grow into a giant tree so she can be a home to forest creatures because of a tale told by Lolo Ninok, a Philippine scops owl. The illustrations by Aaron Asis are wonderful! The artist’s work is the puzzle piece that completes the narrative.

What do you hope children will learn after reading your book?

I am hoping that children will be more aware of how magnificent and valuable trees are, that planting native trees is beneficial to the environment because they are more resilient against strong winds and flooding brought about by typhoons. Also, endemic species prefer to live in native trees.

Jomike Tejido

Jomike Tejido

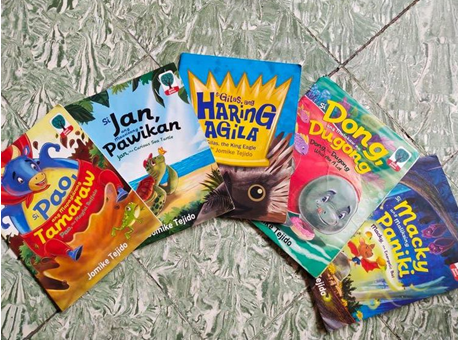

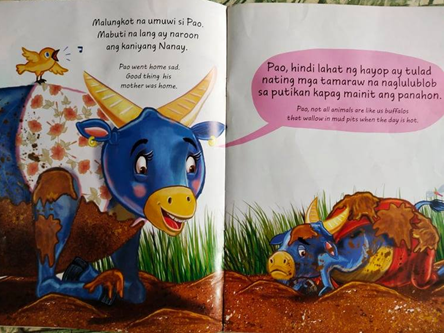

Jomike Tejido is both a writer and illustrator with over 50 children’s books under his belt. In 2010, he won two National Book Awards for writing and illustrating Tagu-Taguan, and for illustrating Lub-Dub, Lub-Dub about pioneering pediatrician Fe del Mundo. Also an architect, Jomike has been writing children’s picture books since 2001. One of them is the Anvil-published endangered species series, which features lovable stories about the pawikan (marine turtle), dugong, Philippine eagle, and tamaraw (Mindoro dwarf buffalo) among others.

5 of 7 books in Jomike’s endangered species series

5 of 7 books in Jomike’s endangered species series

How did the concept for the endangered species series come about?

The series was commissioned by Anvil Books in 2007 and it was my first experience in having a commissioned set of three stories. Then the series picked up and more titles sprang. They must have commissioned me for it due to my long-running daily comic strip that dealt with the lighter side of environmental issues. Mikrokosmos in the Philippine Daily Inquirer ran from 2000 to 2007.

How did you craft the stories?

I took into consideration some pointers I learned from the writers’ workshop I attended, wherein a child psychologist talked about a child’s psychological needs. From there, I made my stories more mundane and specific. Pao Tamaraw was inconsiderate and playful, while Gilas Agila was boastful and had a superiority complex. All these traits are flaws relatable to children, and personified by animals in their habitat. As children can sometimes act like “wild animals,” I could easily relate animals to kids. I worked with Haribon Foundation, and I had a pack of endangered animal flashcards I used as my main list. Then I worked with credible websites to fill in other factual details.

What do you think are the strongest points of this series?

The strongest points are my low word count (thus short storyline), relatable characters and whimsical digital art. I made it a point that the science part wasn’t didactic or rammed into the readers’ minds.

What do you hope children will learn after reading these books?

I hope that children can learn to love animals, especially those endemic to our country, and not feel that just because they are local, they are uncool. I’d like young Filipinos to be proud that these creatures come from their land. I want them to know where these animals live and what they eat, just like how kids are familiar with foreign creatures from TV or books.

Augie Rivera

Augie Rivera

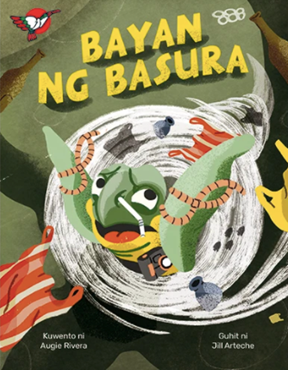

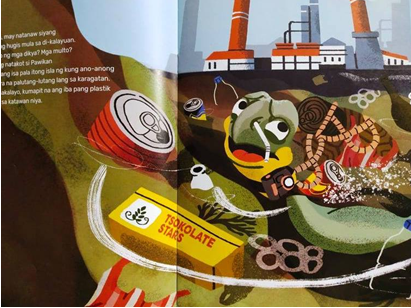

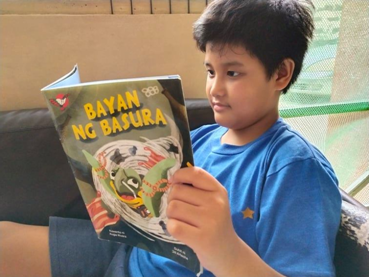

Writing for the classic Filipino children’s show Batibot propelled Augie Rivera to be a children’s book writer. His books have received recognition from award-giving bodies, including the prestigious Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature. Recently, he was awarded with the 2020 Gawad Pambansang Alagad ni Balagtas for Children’s Literature in Filipino. Last year, Augie’s 19th book, Bayan ng Basura, illustrated by Jill Arteche, was published by Adarna House and Greenpeace Southeast Asia – Philippines. The protagonist is a pawikan who, after a storm, ends up in the deep end of the ocean littered with trash and ailing fellow sea creatures.

How did you come up with the story’s concept?

The book was commissioned by Greenpeace because they wanted to tackle the issues of single-use plastics and ocean pollution. I based the story on real-life events, such as the marine turtle that had a plastic straw shoved up its nose in Costa Rica in 2015. I also read up on the dead whale in Compostela Valley which had 40 kilograms of plastic in its stomach. Then I saw a footage of a British diver in Bali who showed the incredible amount of garbage floating on the sea. These bits of news fueled my imagination, which was why my story had a post-apocalyptic feel to it, wherein there was more garbage than sea creatures.

What do you think are your book’s strongest points?

I really like the book illustrations by Jill Arteche. The first time I saw them, the style reminded me of Maurice Sendak’s work. When I met Jill, I found out that Sendak is one of her major influences. When the pawikan was surround by trash, the illustrations were dim. They brightened when the trash disappeared.

What do you hope kids will learn from story?

I want them to be aware that they can do something to solve a big problem such as ocean pollution. They can do their part in their own little ways because that’s how big problems start—from little things. I want them to be mindful of their actions because humans are not the only living things here on earth.

Practicing What They Preach

These writers don’t only write about caring for the environment; in their own homes, they also practice eco-friendliness. Liwliwa, for instance, was brought up by a grandmother who taught her how to reuse and recycle. “At home, we try to be mindful of our carbon footprint, conserving water and energy, and refusing single-use plastic.”

Jomike reuses product packaging, and passes on environmental values to his children. “I teach my kids to save water and energy by turning off faucets and appliances when not in use. I let them watch nature documentaries to expand their world view, and see animals wider than the scope of domestic pets,” he shares.

Ever since Augie moved to Marikina a few years ago, he’s been more conscious of waste segregation. “Once, I accidentally mixed vegetable peel with non-recyclable waste, and I had to go to the City Environment Management Office to either pay the fine of P2,000 or do community work. I never made the mistake again.” When he goes out, Augie brings his own eco bag, straw and utensils. “I agreed to write Bayan ng Basura because I really support environmental advocacies.”

Linaaw, Liwliwa’s daughter, reads her mother’s book

Linaaw, Liwliwa’s daughter, reads her mother’s book

Telling Mother Nature’s Stories

All these children’s book writers agree—it’s vital to write environmental stories for children.

“It’s important to imbue the love for animals and care for the environment at a young age,” Jomike shares. “Stories like mine aim to foster the love for these creatures by letting kids feel that these characters are like their friends (or themselves), who have flaws like any normal person and can be taught to become better.”

Liwliwa thinks that these stories are more important now during the pandemic. “Nowadays, children are always indoors, and stories connect them with the outside world,” she says. “Stories about the environment make children realize how nature makes it possible for us to live our lives and how children can participate in protecting our planet.”

Augie believes that stories about the environment gives hope to the next generation. “As grownups, we didn’t do our part in saving our planet. So we should raise our children’s awareness on the issues, and encourage them to do their part and hope for a better world to live in.”