Home > Blog > Pinoys off the Map

Pinoys off the Map: Tsukuba, Japan

Tsukuba, located in Ibaraki Prefecture, takes its name from Mount Tsukuba, famous for its double peaks. But the city is also popular for the Tsukuba Science City, Japan’s center of research and development first developed in the 1960s. Here, one can find the nation’s top research institutes and two national universities dedicated to various scientific fields such as mechanical engineering, chemical research, and robotics. Tsukuba has also provided both local and foreign governments with data on earthquake safety, environmental degradation and plant genetics among others. With a population of under 300,000, Tsukuba is home to both research facilities and sprawling nature—as well as Julius Santillan, a Filipino engineer.

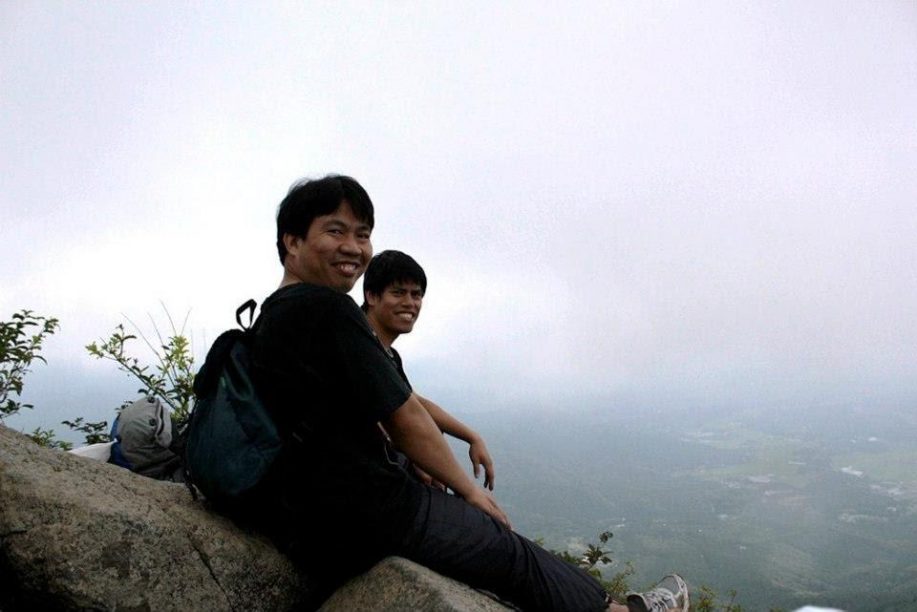

Julius and a friend at the peak of Mt. Tsukuba

Julius and a friend at the peak of Mt. Tsukuba

I was born and bred in Silay City, Negros Occidental—simple life, simple dreams. My father wanted me and my brothers to be engineers because he liked the idea of having the title “engineer” attached to our names. As the eldest of four boys, I felt obliged to fulfill his dream.

I studied at the Technological University of the Philippines (TUP)-Visayas, which had a Japanese Language Program. Our teacher, who was Filipina and studied in Japan, encouraged us to apply for a “Monbusho” Scholarship, an academic scholarship offered by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. So, I did and got in.

In 1998, I flew to Japan to study. Here I met Caryn, a fellow scholar and Filipino, who eventually became my wife. In a foreign land, we studied, eventually worked and raised our two sons.

Photo of Julius featured in a Japanese newspaper

Photo of Julius featured in a Japanese newspaper

Journeying in Japan

After three years of studying in Osaka, I moved to Tokyo to work as an engineer for laser equipment used in eye surgeries among other applications. After a year and a half, I was outsourced in Tsukuba to work on semiconductors so sensitive that I had to wear a suit inside what they called the “super clean room.” This is a room with a strictly-controlled environment that keeps harmful particles (for the semiconductors) at a minimum level. Presently, I’m working for Osaka University but our research allows us to remain here in Tsukuba.

During the first few years working in Tsukuba, my family then was living near Disneyland Tokyo and I’d shuttle back and forth for work. But in 2011, the huge earthquake came and I got stranded in Tsukuba. At that time, Caryn and the kids were in the Philippines on holiday (fortunately) but we decided to relocate to Tsukuba so we could all be together whatever happened. I also thought the good distance from the sea was a plus since we’ll be away from tsunami waves—if ever.

Actual rocket displayed at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency in Tsukuba

Actual rocket displayed at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency in Tsukuba

Tsukuba, City of Paradox

Walking around in Tsukuba is a bit confusing in the sense that expansive high-end laboratories are sandwiched by sprawling rice fields and vegetable farms. If you want to see a place with both farmlands and robots, this is the place.

Signages in Tsukuba

Signages in Tsukuba

In this science city with so many research labs, you’ll meet a lot of PhDs (Doctors of Philosophy). Researchers from all over Japan often find work in Tsukuba, which was why the government built a direct train line from here to Tokyo. Tsukuba is a young city with well-thought out city planning. It is very family-friendly (with parks, bike roads, etc.) so it’s only natural that researchers bring their families to make their home here. As a result, more schools were put up here—high-level elementary and high schools that rank in the whole of Japan. In fact, some Tokyo residents bring their kids to Tsukuba for schooling.

Autumn in Matsuhiro Park

Autumn in Matsuhiro Park

Doho Park

Doho Park

But unlike in Tokyo where supermarkets are a stone’s throw away from my apartment, I have to walk around 10 minutes to buy food—the faster way than taking the bus, which arrives only every 30 minutes. But the parks here are heaven. We’d just go down the apartment and instantly land in the park. There are so many parks here; each community has one. And most of these parks are connected by paths for pedestrians and bikes. If we want to go to the city center, it takes about 25 minutes of walking. But we pass by three parks so the kids get to play in between.

Another interesting tidbit about Tsukuba is it’s hailed as “The Pastry Capital of Japan.” In my neighborhood alone, there are around four bakeries (French, German, Danish, and a Japanese one selling baumkuchen, a traditional German cake). If you want to go on a pastry food tour, it’s best to travel by bike or car as the cafes and bakeries are far from each other. The establishments in Tsukuba, including malls, are usually huge because there’s so much space here.

French bakeshop

French bakeshop

Sweet offerings

Sweet offerings

Away from Family

Caryn and my two boys moved back to the Philippines in 2016 because my eldest son needed therapy. He wasn’t responding well to Japanese teachers, but he was cooperative with his Filipino teachers. So, my wife and I decided it would be best for them to live there, and just visit me once or twice a year.

Traditional house

Traditional house

Springtime near Ninomiya Park

Springtime near Ninomiya Park

At first, it was difficult. Tsukuba is a quiet city. Around 10 pm, it’s dead silent here. No industrial noise, no construction— just the hum of electricity in the apartment. It’s so quiet, I hear the buzz of dragonflies outside my window. I can hear myself think—which was scary at first but is not so bad when I got used to it. Although sometimes, thoughts don’t let me sleep.

I try not think too much about being alone. My parents raised me to always make do with what I have. To cope, I decided to further my studies. The Tsukuba University nearby has a program that allowed me to work while studying. In a year, I completed my papers and got my PhD.

Spring in Matsushiro Park

Spring in Matsushiro Park

The parks, which were my sons’ playground, became my thinking spots. I like reflecting on my present situation and my past self, and marveling at how far I’ve gone.

I’ve also learned to cook. Before, I relied on Caryn to make all the dishes. Now, I’m getting acquainted with ingredients and spices. I’m confident enough to share my cooking when we have potluck parties with other Filipinos.

Music is also an outlet. I compose songs to express myself since I’m not the best in verbally communicating my feelings. I play the guitar, the cajon and bass. I’m also in a band with Pinoys I’ve interacted with—former students, teachers and co-volunteers at the Japanese embassy. At present, we get to collaborate through the internet.

National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science

National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science

Tsukuba and the Pandemic

The pandemic impacted my already limited social life. When Caryn was here, our home was a haven for Pinoy students who wanted a piece of home. My wife would cook for them, and I’d entertain them with jokes. When my family went back to the Philippines, I maintained those friendships, but because of the pandemic, I don’t get to see our friends anymore. Now, my conversations are only with my boss, our engineer, and the people who man the supermarket and convenience store near my apartment!

Seriously though, living in Tsukuba has its advantages during the pandemic. There’s so much space here, so people can practice physical distancing without effort. It’s not like Tokyo where you have to hunch your shoulders to avoid bumping into people. Here, we have abundant personal space. You can walk for several minutes without seeing anyone (I don’t know if that’s a good thing). The parks are so huge, you’ll have no problem finding solitary spaces.

We only have a few cases but since Tsukuba is connected to Tokyo, the place with the greatest number of infections at this time, everyone is cautious. The Japanese government encourages its citizens to install a contact tracing app in their smartphones. If you spend more than 10 minutes talking to someone, your phones leave a record through Bluetooth communication. When the person you’ve talked to tests positive for COVID-19 and registers it through the app, it will contact people he’s interacted with and recommends that they also get tested.

Restaurants remain open during this pandemic though takeouts are highly encouraged.

Restaurants remain open during this pandemic though takeouts are highly encouraged.

Home away from Home

After 22 years of living in Japan, I’ve fully adjusted to the culture. Though the Philippines will always be home to me, Japan has also provided me a nest that gives me comfort. There’s no more language barrier for me. Nihongo may be simple, but also very nuanced. Sometimes, the Japanese don’t say things directly. I’ve learned to read between their lines to understand what they’re not saying but saying—if you know what I mean.

Summertime on the bike path near the Tsukuba International Conference Center

Summertime on the bike path near the Tsukuba International Conference Center

Although I’ve adjusted here, I’d still like to retire in the Philippines. It’s where my family lives, the place I’m most comfortable in.

But for now, I accept my life’s paradox, just like how Tsukuba is a city of both rural farmlands and pioneering scientific breakthroughs. In order to better provide for my family, I need to be away from them. It’s a story all overseas Filipinos share, and an unfolding story, which, I hope and believe, will end happily.