Most Filipinos would not rather think about disasters now that Christmas is around the corner; but the fact that the world is in the middle of a pandemic shows that crises can strike at any given time.

Given the country’s location within the Pacific Ring of Fire, and that the Philippines experiences the most number of typhoons than anywhere else in the world, Filipinos should make disaster preparedness a daily habit and part of their culture.

To help achieve this, Panahon TV, which has long advocated disaster preparedness from its birth almost a decade ago, has a timely and useful gift for Filipinos this holiday season—the gift of disaster preparedness. A free webinar moderated by Panahon TV Reporter Patrick Obsuna will feature distinguished speakers and veterans in the field of disaster preparedness. Martin Aguda, author of Ready 101 and national representative to the International Association of Emergency Managers will talk about risk awareness, emergency planning, acquiring survival supplies, and the skills and drills needed to survive disasters. Meanwhile, Sandy Montano, an earthquake survivor and the CEO of Community Health Education Emergency Rescue Services (CHEERS) will shed light on government response during disasters, and the important role of women in preparedness.

Disaster Preparedness during the Pandemic will air on December 22 at 2 pm. Though the webinar is free, monetary donations are welcome and will be given to the Philippine Disaster Resilience Foundation for victims of Super Typhoon Rolly and Typhoon Ulysses.

To join the webinar, register here: https://bit.ly/2LBm5X3

Just after midnight on August 17, 1976, a magnitude 8 earthquake shook the areas around Moro Gulf in Mindanao, including Cotabato City. But the disaster did not stop there; less than 5 minutes later, a tsunami as high as 9 meters roared and swallowed 700 kilometers of coastline. When the sea ebbed to its peaceful state, around 8,000 had died from the combined effects of the earthquake and tsunami, with the latter accounting for 85% of deaths and 95% of those missing and never found. The event, now known as the 1976 Moro Gulf Earthquake, is recognized as the deadliest earthquake that ever hit the country.

Devastation of the 1976 tsunami at Barangay Tibpuan in Lebak, Mindanao (Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Devastation of the 1976 tsunami at Barangay Tibpuan in Lebak, Mindanao (Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Almost two decades later on November 15, 1994, Mindoro was rocked by a magnitude 7.1 earthquake. Like what happened in Mindanao, majority of the 78 casualties of the Mindoro earthquake was due to the 8-meter high tsunami that occurred 5 minutes after the quake.

The truth is, though Filipinos are aware of devastating tsunami happening in other countries like Japan and Indonesia, they do not often associate these natural disasters in their homeland. But as past events indicate, deadly tsunami can occur locally. As Undersecretary of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) for Disaster Risk Reduction-Climate Change Adaptation (DRR-CCA) and Officer-In-Charge of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) put it, “Tsunami are very fast in the Philippines and we need to prepare for them.”

Tsunami 101

In observance of World Tsunami Awareness Day last November 5, PHIVOLCS organized an online press conference to spread the word about tsunami. Mostly generated by under-the-sea earthquakes, tsunami are characterized by a series of waves with heights of more than 5 meters. According to Solidum, such earthquakes can be triggered by underwater landslides, volcanic eruptions, and the more unlikely meteor impacts. These cause the seafloor to lift, causing the water it carries to rise.

There are two types of tsunami—the distant and local. Distant or far-field tsunami is generated outside the Philippines, mainly from countries bordering the Pacific Ocean like Chile, Alaska (U.S.) and Japan. With these events being monitored by The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC), the Philippines has 1 to 24 hours of preparation before the tsunami’s arrival, depending on its origin.

But with local tsunami, lead time is cut down to a mere 2 to 10 minutes after the earthquake. “Preparedness is very important because rapid response is needed for locally-generated tsunami. The trenches are where the large earthquakes and tsunami can be generated, and we are only the country wherein trenches can be found on both sides. Hence, both sides of the country need to prepare for tsunami. Aside from that, the eastern side of the country faces the Pacific Ocean or the Pacific Ring of Fire where earthquakes and tsunami can also be generated,” said Solidum.

What PHIVOLCS is doing

Part of the Tsunami Risk Reduction Program of PHIVOLCS are the Tsunami Hazard Mapping and Modeling, and the Tsunami Hazard Risk Assessment, both of which aim to understand tsunami, manage their hazards and risks, and identify priority actions for response and recovery. To detect possible tsunami, PHIVOLCS set up its Monitoring and Detection Networks Development.

Aside from the 107 seismic stations that receive data for earthquakes and tsunami, there are also 29 real-time tide gauges all over the country. Through the hazards and risk-assessment software code REDAS, PHIVOLCS can evaluate potential earthquake hazards, create tsunami simulations, and predicting the number of affected people. “The total population exposed to tsunami would be close to 14 million,” said Solidum. “But they will not be affected at the same time. It would depend on where the tsunami would occur. In NCR, for example, the prone population would be around 2.4 million. And the next highest would be 1.6 million in Region VII, 1.2 million in Region VI— and in Region IXA, around 1 million.”

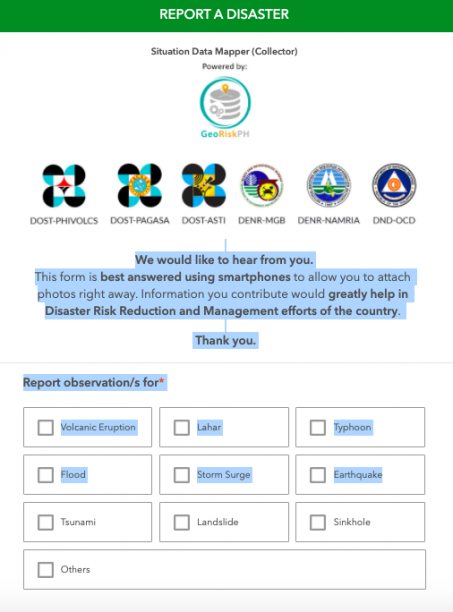

Meanwhile, HazardHunter Philippines, which is open for public use, can assess hazards depending on the user’s specific location. “HazardHunter can also give you a more detailed tsunami hazards assessment because it can provide you a map showing the different areas that will be affected by different tsunami heights. It is color coded, indicating areas prone to various tsunami heights.” Solidum appealed to the public to take advantage of the “Report a Disaster” website. Here, people can post pictures and videos of current risks and hazards in their areas, and describe disasters impacts, which can help the government’s risk and impact assessments.

Screencap of “Report a Disaster” website

Screencap of “Report a Disaster” website

“In the Philippines, we use a simple tsunami information or warning scheme,” explained Solidum. “We will evacuate once the tsunami information is categorized as a tsunami warning. We expect a destructive tsunami of more than 1 meter and this would need immediate evacuation of coastal areas. Boats at sea are advised to say offshore — in deep waters.”

Shake, drop and roar

Because local tsunami can be very fast, people need to know its natural signs:

Shake – refers to a strong earthquake.

Drop – refers to the sea level receding fast.

Roar – refers to the unusual sound of the returning wave, which indicates a tsunami.

After an earthquake, Solidum recommends for people near the shore to immediately move to elevated ground inland, or take refuge in tall and strong buildings. “If they have not moved at all, once they hear the tsunami and there are unusual sounds, there might not be enough time. They really need to respond immediately,” warned Solidum.

PHIVOLCS also released tsunami safety and preparedness measures on their website:

- Do not stay in low-lying coastal areas after a felt earthquake. Move to higher grounds immediately.

2. If unusual sea conditions like rapid lowering of sea level are observed, immediately move toward high grounds.

3. Never go down the beach to watch for a tsunami. When you see the wave, you are too close to escape it.

4. During the retreat of sea level, interesting sights are often revealed. Fishes may be stranded on dry land thereby attracting people to collect them. Also sandbars and coral flats may be exposed. These scenes tempt people to flock to the shoreline thereby increasing the number of people at risk.

Solidum stressed the importance of community-based preparedness, built on planning and drills to create the following output:

- development of evacuation plans based on the hazard maps

- installation of different types of signage (signage for hazards, signage for the evacuation area, signage for the directions to go to the evacuation area)

- conducting of seminars and lectures

- drills

Tsunami preparedness during COVID-19

The devastation of several typhoons this year, coupled with the country’s location in the Pacific Ring of Fire, are proof that the Philippines is prone to various hazards. Because of the

COVID-19 pandemic, Solidum admitted that PHIVOLCS had to rethink their training methods. “Before, we actually go down to various coastal communities and conduct lectures in the evening, so that people who worked in the daytime can also attend. But the pandemic has enabled more people to listen because of the social media platform and our webinars. We’ve reached more people in terms of information campaign. But we hope that local government disaster managers will do the actual preparedness at the community level.”

Solidum noted that though COVID-19 continues to cause loss of lives and the disruption of public services, mobility and economic development, tsunami can create far more devastating impacts. “We will see the physical impacts through buildings, infrastructures, property, water supply pipes, electrical supply, communication system, roads, bridges, and ports. This is in addition to the physical impact on people because of the collapsing houses or the impact of the large volume of water. We have science, technology, and innovation from DOST that can help in preparedness and disaster risk reduction. We need to use it, but we need to share this information to the communities and the public,” he ended.

Watch the full press conference from PHIVOLCS.

Watch Panahon TV’s primer on tsunami.

In 2019, “climate emergency” was chosen as the Word of the Year by the Oxford Dictionaries, which defined it as a “a situation in which urgent action is required to reduce or halt climate change and avoid potentially irreversible environmental damage resulting from it.”

Since the United Kingdom’s climate emergency declaration in 2016, more than a thousand local governments in 28 countries have made their declarations, pushing for more urgent measures to address global warming.

In the beginning of 2019, then 16-year-old Greta Thunberg, a Swedish environmental activist, urged global leaders who attended the World Economic Forum to act on climate issues. Her now infamous words, “Our house is on fire,” sparked youth-led environmental rallies all over the globe. On September 20, 2019, around 4 million people worldwide took the streets to participate in Global Climate Strike, the biggest climate protest in history.

Greta in 2018, participating in a Helsinki rally

Greta in 2018, participating in a Helsinki rally

Why Climate Emergency Became a Buzzword

2019, which marked the last year of the hottest decade on record, saw a wave of climate emergency declarations across the globe. It was also the year when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its first comprehensive report on how agriculture and other forms of land use worsen climate change, and vice versa. With rising temperatures come extreme weather events, droughts, forest fires and pest outbreaks that threaten global food supply.

The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) supplemented these findings with a report published on the International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction last October 13. The UNDRR report on the human cost of disasters from the past 20 years (2000-2019) showed a staggering 45% increase in major recorded disaster events, compared to data gathered between 1980 and 1999. In the past two decades, over 7,000 disasters claimed more than a million lives, resulting in global economic losses of US$2.97 trillion.

Majority of the disasters are climate-related, particularly floods—which have doubled in the last twenty years— and storms, which increased by almost 40 percent. Major increases were also observed in droughts, wildfires and extreme temperature events.

With these planet-threatening climate impacts, climate emergency declarations seek to compel all sectors of society, including the government, businesses and the media, to recognize the need to take immediate action.

Indonesians joining the Global Climate Strike on Sept. 20, 2019

Indonesians joining the Global Climate Strike on Sept. 20, 2019

Declaring a Climate Emergency in the Philippines

The Philippines has yet to declare a climate emergency, something which environmental group Greenpeace has been pushing for since December last year, when Typhoon Tisoy devasted Northern Samar and Bicol, prompting provinces to issue a state of calamity. The typhoon, which halted Manila’s airport operations for twelve hours, forced hundreds and thousands of people into evacuation centers, and left 17 dead.

Greenpeace activists marched to Malacañang, calling on President Rodrigo Duterte to immediately declare a climate emergency. “Year after year, Filipinos are identified among the most impacted globally by this crisis, an emergency situation made worse by the big polluters—fossil fuel companies who have lied and covered up about how their operations have been driving the climate crisis and who have been raking in trillions in profits at the expense of millions of people who suffer from its impacts,” said Lea Guerrero, Country Director of Greenpeace Philippines.

According to the Germanwatch-published Global Climate Risk Index 2020, the Philippines ranked 2nd in the counties most affected by impacts of weather-related loss events in 2018. But in terms of facing the highest risk of climate change hazards, the country topped the list of the Global Peace Index. Greenpeace stressed the need for climate impacts to be addressed since the country’s poorest regions and provinces are the most prone to sea level rise, extreme weather events, and landslides.

Typhoon Tisoy’s devastastion in Legazpi City, Albay

Typhoon Tisoy’s devastastion in Legazpi City, Albay

Climate Emergency and the Pandemic

This year, Greenpeace renewed its call for a climate emergency declaration, pushing for climate action and climate disaster risk reduction to be at the heart of the government’s COVID-19 recovery plan. “Unless the worst impacts of the climate crisis are averted, the cost in human lives and economic losses will continue to rise to catastrophic proportions,” said Greenpeace Philippines Climate Justice Campaigner Virginia Benosa-Llorin. “The Duterte administration must use the opportunity of the COVID recovery to build in strong climate action into a response that will enable the country to weather other future crises that may happen alongside the climate emergency.”

A way to do this is to maximize renewable energy (RE) sources, also strengthening the country’s commitment to the the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, which aims to keep global temperatures below 1.5 degrees. According to Greenpeace’s Southeast Asia Power Sector Scorecard, the Philippines was an early leader of RE after the introduction of the 2008 RE Act. But through the years, this commitment died down, causing coal to make up more than half of the country’s energy mix. Because of this, the country has grown dependent on imported fossil fuels, which have tripled in less than a decade.

But the report states that isn’t too late to make a turnaround. If the country transitions to RE, increasing it to 50% by 2030, it can still meet its global climate targets while ensuring a better recovery after the pandemic. Allocating the national budget for eco-friendly measures on health, energy, transport, water, food, waste and education, is believed to strengthen the country’s resilience and sustainability.

Less Talk, More Walk

Greenpeace demands the following concrete steps from the government:

- Putting climate urgency at the heart of policy decision-making from local to national levels.

- Holding fossil-fuel companies accountable for driving climate change and inflicting harm on the Filipino people.

- Demanding industrialized nations to enhance their emissions reduction ambitions in order to meet the Paris Agreement

- Ensuring the Philippines’ rapid and just transition to a low-carbon pathway through a massive uptake of renewable energy solutions

- Phasing-out coal, and stopping all plans for future coal and fossil fuel investments

Last October, Department of Energy Secretary Roy Cimatu, who also heads the Cabinet Cluster on Climate Change Adaptation, Mitigation and Disaster Risk Reduction, released a statement in favor of the country’s declaration of a climate emergency. “The Philippines has already suffered billions of losses, damages and disruptions due to the impacts of hydrometeorological hazards, so there’s an urgent need to address more projected adverse impacts to ensure climate justice for the current and future generations of Filipinos,” Cimatu said.

In the meantime, Greenpeace and other environmental groups continue to monitor the government’s decisions and actions to make sure that their words are concretized by effective action.

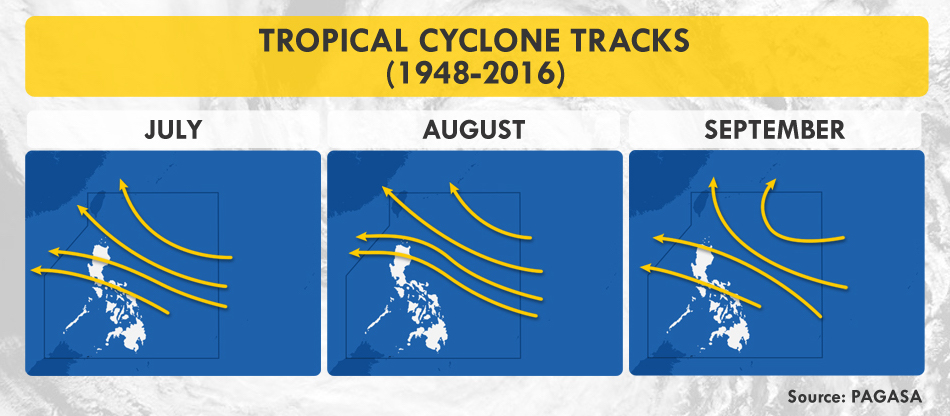

Managing the rainy season this year is vastly different from the previous ones as the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) continues to pose threats on the country’s public health, economy, and environment. During this time, tropical cyclones, combined with the enhanced southwest monsoon (habagat), are expected to bring floods, storm surges, destructive winds, and landslides which may hamper efforts in curtailing the spread of the virus. According to the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), 6 to 10 cyclones may enter the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) from July to August. Additionally, there is a 50% chance that La Niña may develop in the last quarter of the year, bringing wetter conditions in the eastern section of the country.

Typhoon Season. Two tropical cyclones have traversed the PAR since the first COVID-19 case in Manila on January 30. Typhoon Ambo, internationally known as Vongfong, made landfall six times on May 14 and 15, while Tropical Depression Butchoy hit the landmass twice on June 11. Both pummeled the coronavirus-stricken Luzon.

Typhoon Season. Two tropical cyclones have traversed the PAR since the first COVID-19 case in Manila on January 30. Typhoon Ambo, internationally known as Vongfong, made landfall six times on May 14 and 15, while Tropical Depression Butchoy hit the landmass twice on June 11. Both pummeled the coronavirus-stricken Luzon.

Aylen Labiano, who has been selling agricultural products beside an ecotourism road in Lucena, Quezon for nearly a year now, recounts in Filipino how Bagyong Ambo impacted her livelihood. “The recent cyclone devastated vegetation and banana trees, which prompted suppliers and sellers to raise prices. But people want low-cost food since a lot of them lost their jobs, and the situation has not yet normalized. If typhoons continue to ravage our livelihood, we will not be able to make ends meet.”

Agricultural Uncertainty. Agricultural loss due to Typhoon Ambo is estimated at Php1.37B.

Agricultural Uncertainty. Agricultural loss due to Typhoon Ambo is estimated at Php1.37B.

19-year old Carl Ian Pedregosa from San Francisco, Quezon shares how his family monitored the news to prepare for the typhoon. “But when the rains arrived, we experienced power outage, which lasted for more than a week. Some coconuts, which were supposed to be extracted for oil, also fell during the storm. We fed them to the hogs instead.” Pedregosa also worries about how power interruptions can not only make it difficult for his family to stay updated, but also disrupt his education in the coming school year, especially with academic institutions planning to utilize online learning.

Felled coconut trees in Quezon Province, one of the top agricultural producers of copra in the country.

Felled coconut trees in Quezon Province, one of the top agricultural producers of copra in the country.

PAGASA Cyclone Forecast

PAGASA Cyclone Forecast

Overwhelming Complications

While studies say that rain may help dilute the virus on contaminated surfaces, it also favors other diseases that may strain our healthcare system.

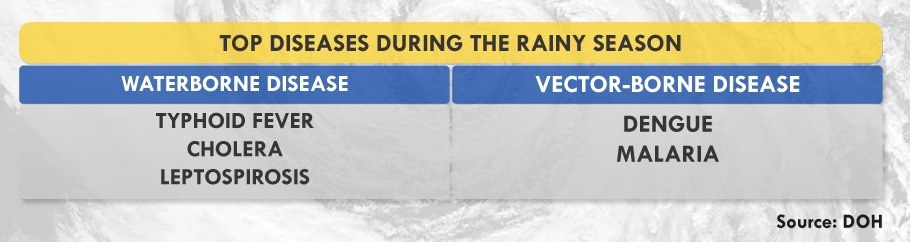

Monsoon Diseases. With the rains comes a downpour of diseases, ranging from the easily curable, such as diarrhea and cough, to the downright deadly, including leptospirosis and typhoid fever. Meanwhile, the World Health Organization (WHO) clarifies that there is still no evidence supporting the possible transmission of COVID-19 through mosquitos and houseflies. To date, no peer-reviewed studies have proven that the ongoing seasonal change has weakened the potency of the virus, and if it can interact with other viruses to develop worse symptoms.

Monsoon Diseases. With the rains comes a downpour of diseases, ranging from the easily curable, such as diarrhea and cough, to the downright deadly, including leptospirosis and typhoid fever. Meanwhile, the World Health Organization (WHO) clarifies that there is still no evidence supporting the possible transmission of COVID-19 through mosquitos and houseflies. To date, no peer-reviewed studies have proven that the ongoing seasonal change has weakened the potency of the virus, and if it can interact with other viruses to develop worse symptoms.

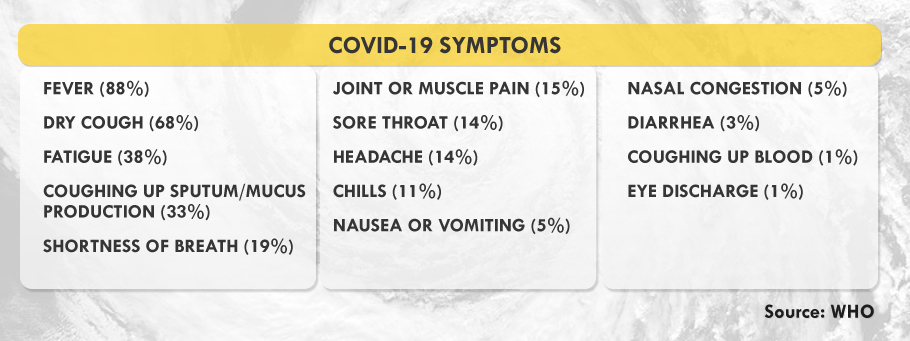

But the real problem lies with how symptoms of monsoon diseases are almost similar to those of COVID-19’s. “Whether people tested positive or negative for COVID-19, we will need to test them for other possible diseases which will make the process longer,” states Dr. Generoso Roberto of the Philippine Society of Public Health Physicians (PSPHP).

The Department of Health (DOH) targets to license 65 COVID-19 testing laboratories by the end of July to test 1.5 to 2% of the population. To date, there are 62 accredited labs with a rated testing capacity of 50,000 daily, prioritizing suspect cases, individuals with travel history, and healthcare workers with possible exposure, whether they are symptomatic or asymptomatic. However, there is still a gap between rated and actual capacity with 12,000 to 16,000 people tested a day due to manpower and supply chain issues— problems that arise globally.

Confirmed Symptoms. The United Kingdom has included anosmia, or loss of taste or smell, as a predictor for COVID-19. Experts say that patients infected with COVID-19 usually transmit the disease before their symptoms manifest, their ability to infect peaking until the third day after symptoms start showing.

Confirmed Symptoms. The United Kingdom has included anosmia, or loss of taste or smell, as a predictor for COVID-19. Experts say that patients infected with COVID-19 usually transmit the disease before their symptoms manifest, their ability to infect peaking until the third day after symptoms start showing.

“We also need to plan where we’ll be admitting patients diagnosed with other diseases if certain hospitals are designated as COVID-19 treatment sites,” Dr. Roberto explained. Meanwhile, people living in rural areas, especially in remote islands, will face the challenge of transporting patients and doctors to the barrios during the typhoon season. “This means that patients can develop severe symptoms by the time they’re brought to healthcare facilities,” Dr. Roberto explained.

Though virtual healthcare seeks to keep patients at home, the system is not inclusive of, and accessible among the marginalized. According to the Speedtest Global Index, upload and download speeds for mobile and fixed broadband in the country are still below the global average. The Social Weather Stations (SWS) also shows that only 22.4% of Filipino families in the country owns a personal computer at home.

Rising Tide of Vulnerabilities

The country is still on its first wave of COVID-19 cases when the government gradually eased quarantine measures, allowing some businesses to reopen. Though this move aims to save the economy from socioeconomic impacts, such as unemployment and hunger, it may also worsen, not only the health crisis, but also disaster risks.

“We need to do scenario building or disaster imagination so we can prepare for complex emergencies,” says Science and Technology Undersecretary Renato Solidum, Jr. in Filipino. Government and private sectors should have continuity plans for their public service and businesses since the pandemic may coincide with hazards that often transpire in the country, such as earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions.

On March 11, days before the Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) in Luzon, volcanologists placed Mount Kanlaon in Negros Island under Alert Level 1, prohibiting people around its 4-kilometer-radius danger zone for possible sudden phreatic eruptions. A series of volcano-tectonic quakes has been observed since June 21. Meanwhile, Mayon Volcano has been under Alert Level 2 since March 2018.

Urbanized cities are highly exposed both to the pandemic and the negative impacts of natural hazards due to their dense structures and population. According to Solidum, the government’s Balik-Probinsya program may be a good solution to decongest cities as long as comprehensive safety protocols are strictly employed. This program, institutionalized through Executive Order No. 114, seeks to encourage people, especially the informal settlers, to return to their home provinces.

Metro Manila, considered as the seat of government, is no exception to looming catastrophe. Here lies the biggest portion of the West Valley Fault (WVF), an active earthquake generator traversing Bulacan, Quezon City, Marikina, Pasig, Taguig, Muntinlupa, Rizal, Laguna, and Cavite. These areas are part of the Greater Metro Manila Area (GMMA), a megacity with an estimated population of 20 million. About 35% of its populace are informal settlers, many of them living below poverty line.

WVF’s massive earthquakes occur every 400 to 600 years. Its last movement that caused a magnitude 5.7 quake was in 1658 or 362 years ago. According to a joint study by Australia and the Philippines, the fault’s next movement may produce a magnitude 7.2 earthquake, resulting in 34,000 deaths due to collapsed buildings—and an additional 18,000 fire-related fatalities in the metropolis. Furthermore, infrastructures, lifelines, and about 40% of residential buildings are likely to be heavily or partially damaged, causing 2.3 trillion pesos worth of damage. The management of such a huge disaster requires close coordination, which the current pandemic hampers.

If protocols are not properly implemented and followed, evacuation centers during disasters coupled with monsoon diseases may be a breeding ground for more health risks. A person with COVID-19 may infect dozens of people, including Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM) officers who are on the frontline during rescue and relief operations.

One of which is Alex Pimentel, a DRRM officer in Batangas City, who tested positive for the disease in April. “Parang nandidiri ang ibang tao sa community, lalo na when I tested positive,” he shares. (When I tested positive, people in the community avoided me like the plague.)

DRRM offices help by providing transportation for COVID-19-related patients, manning centers for Persons Under Monitoring (PUM), and disinfecting public spaces, among others. But if a natural disaster strikes, people like Alex will even have a more difficult time doing their duty. “It will be hard for the DRRM frontliners responding with merged Search and Rescue and COVID-19 personal protective equipment. We also worry about funds because we’ve already spent so much during the Taal eruption, assisting 11,000 evacuees, followed by the pandemic response.“

Nasugbu, Batangas LDRRMO

Nasugbu, Batangas LDRRMO

The Need for Disaster Imagination

Solidum explains that disaster imagination means preparing for worst-case scenarios and their possible impacts. “People and the Local Government Units (LGUs) should know the hazards in their areas so they can plan appropriately. What if an earthquake transpires? What are its impacts? Have we identified the vulnerable population? Where are we bringing them?”

A study conducted by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in 2014 exposed that more than 90% of evacuation sites in Eastern Samar were partially or completely devastated during the onslaught of Typhoon Haiyan, locally known as Yolanda. These were churches, schools, and community centers, which were identified by LGUs as safe.

On June 13, the Office of Civil Defense (OCD) provided LGUs with guidelines so they can meet the health standards of the COVID-19 National Task Force in conducting online Pre-Disaster Risk Assessment. This allows LGUs to prepare their inventory of resources, logistical requirements, relief packs, and evacuation centers. “If we conduct pre-emptive evacuation, we see to it that everybody is protected. We should be observing social distancing and we limit the number of people in the evacuation centers. We also see to it that our responders are protected,“ says OCD’s Operations Service Director Harold Cabreros.

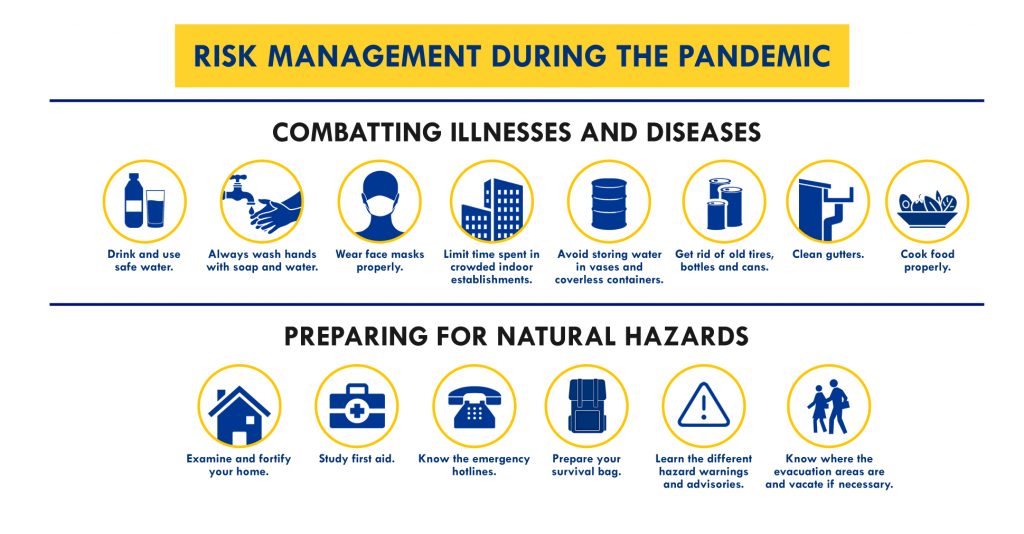

Risk Management during the Pandemic

The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS), PAGASA, and the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB) have developed Hazard Hunter, a tool that Filipinos can use to assess seismic, volcanic, hydrometeorological, and climatological hazards in their locations. It is free and readily- available online, especially useful for property owners, buyers, land developers, planners, and other stakeholders.

It is also important to know what to do before, during, and after several natural hazards.

Graphics by Jearom Andre Martinez

Graphics by Jearom Andre Martinez

This global crisis is not just about adapting to changes, but also preparing for complex emergencies. With inclusive, sustainable solutions, everyone—even the weakest—can be empowered to rise up to the challenges.

Assistance and additional reports from: Fritzjay Labiano, Relly Bernardo (Antipolo PIO), Vic Simoun Montoso, Mark Cashean Timbal (OCD), Lilia Malabuyoc (OCD)