Donna May Lina with Agay Llanera

It’s been a little over a year since the Philippines reported its first COVID-19 case. Since then, our lives have drastically changed. To reduce the spread of the virus, we all had to learn the basic protocols: wash our hands, wear a mask, maintain physical distance. Guidelines were set out on international, national and barangay levels.

Just a few weeks ago, Lowy Institute, an Australian think-tank group, compared the effectiveness of the different countries’ pandemic responses. Criteria included the numbers of reported cases and deaths, tests conducted, and the rates of positive tests. On the list, the Philippines ranked 79th in terms of COVID-19 performance. Top countries that were able to control the virus were New Zealand (1st), Vietnam (2nd), Taiwan (3rd) and Singapore (13th).

(Source: Lowy Institute)

(Source: Lowy Institute)

What did they do right?

For one, these countries have very clear guidelines. The New Zealand government has created separate COVID-19 safety websites for specific audiences—the business and service sector, workers, and even for its construction industry. Taiwan has only seven pandemic-related deaths because of its tight entry restrictions. As early as February last year, travelers with Taiwanese mobile numbers have been utilizing the QR code system for health declarations. Even home quarantine and isolation monitoring are done via mobile phones; if a person left quarantine, his or her phone will alert authorities who will immediately verify the person’s location.

With clear guidelines come clear penalties. To compare how the Philippines compares with other countries in meting out fines for the simple safety protocol of wearing face masks, Panahon TV came up with this chart:

With local government units in our country having their own penalties, guidelines become confusing especially for travelers. A quick web search on sanctions for those failing to comply with COVID-19 safety protocols also revealed the following:

- New Zealand nips irresponsible behavior in the bud by imposing a fine of NZ$4,000 (₱14,000) for travelers who refuse to test for COVID-19. Violators can be held for 28 days.

- In Vietnam, those who escape quarantine sites, avoid quarantine measures, and fail to complete health declarations face criminal punishment.

- When an OFW left his room at a quarantine hotel in Taiwan for eight seconds, he was fined NT$100,000 (₱172,000).

- Those who fail to comply with Stay-Home Notice requirements in Singapore may be penalized up to S$10,000 (₱360,000) and/or imprisonment of up to six months.

- The farthest the Philippine government has gotten in this area is the mere suggestion of imposing community service and fines for quarantine violators. As of writing, no clear penalties have been drafted.

Factors that Contribute to Pandemic Response

Politics and location play a big role in the different pandemic responses across the globe. Vietnam and Taiwan are known for their disciplined citizens because they have always been challenged by threats of war. Due to geographical reasons, New Zealand has learned to be self-contained. A strict compliance with laws has always been the key component of Singapore’s governance.

Culturally, these countries have a more collectivist culture. Social psychologists define collectivism as a value that emphasizes interconnectedness, prioritizing a society’s goal and needs over those of the individual.

Interestingly enough, countries known for their individualistic cultures seem to have weaker pandemic responses, as listed by the Lowy Institute’s report. These include Sweden (37th), the UK ( 66th), Netherlands (75th) and the U.S. (94th).

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention commentary observes how COVID-19 measures seem to focus more on individual risks, which lead to gaps in response. In order to curtail the global spread of the virus, messaging should promote cultural inclusivity. But instead of pitting one culture type against the other, the commentary suggests embracing “multicentric logics – individual, collective, and everything in between.” Different cultures and attitudes are factors in seeing how countries will be able to implement, comply, and continue to maintain safety guidelines to this date.

(photo by Jire Carreon)

(photo by Jire Carreon)

How will the pandemic end?

In an attempt to answer this question, the New York Times discussed how the 1918 Spanish flu virus, which killed as many as 100 million people worldwide, has simply lost steam, evolving into a still potentially fatal seasonal flu.

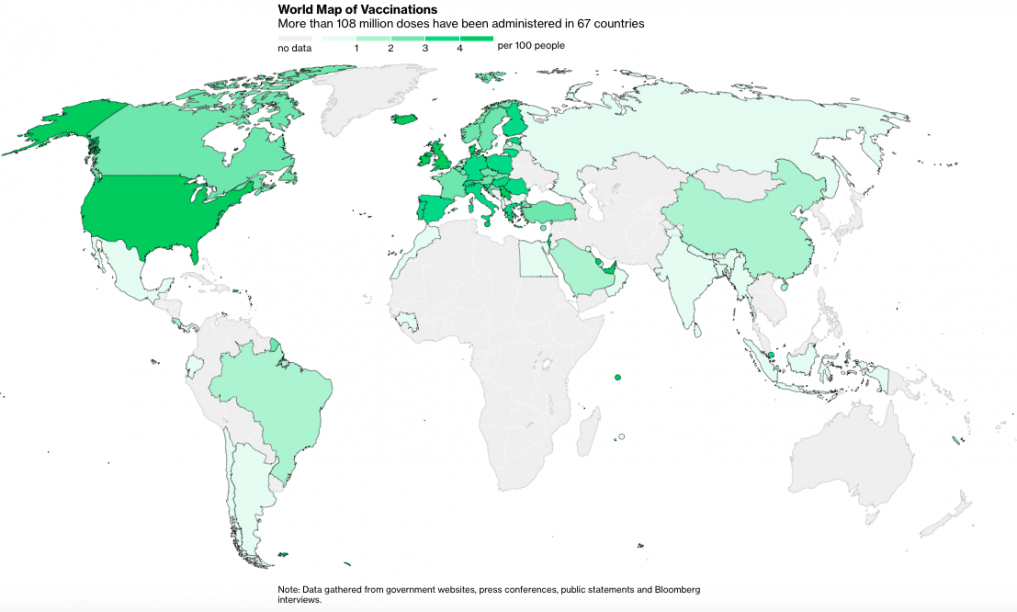

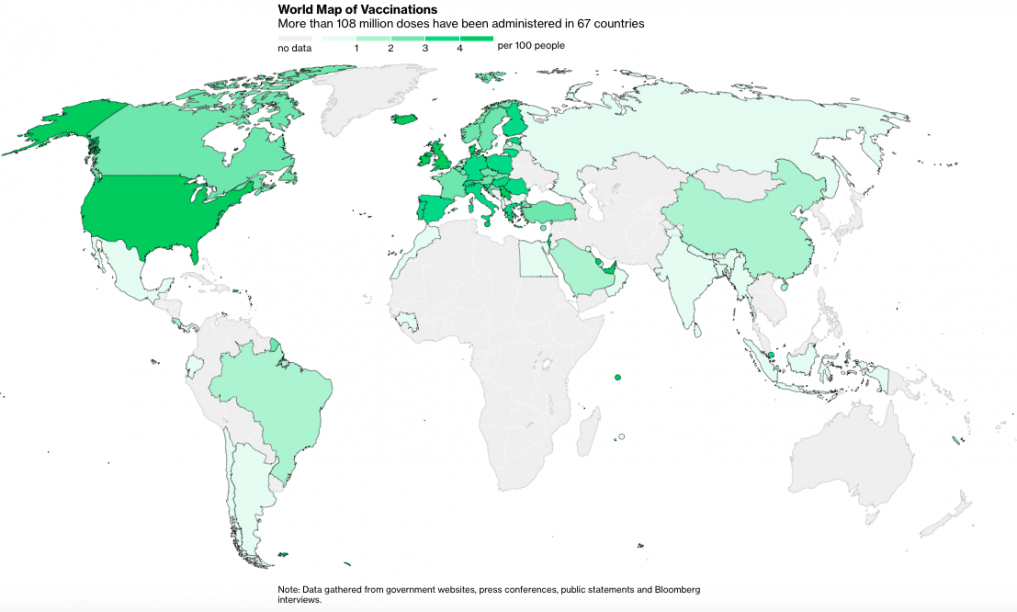

With the vaccine race “won” in round one by pharmaceutical companies like Moderna (U.S.) and AstraZeneca (UK), more than 108 million vaccine doses have been administered in 67 countries.

(Source: Bloomberg)

(Source: Bloomberg)

The vaccines were developed through collaborating scientists, were tested among selfless volunteers, and rolled out to countries’ frontliners and vulnerables depending on government strategy. Through modern technology and cooperation, vaccination has been conducted through Emergency Use Authorization, allowing the release of unregistered drugs and vaccines during a public health emergency. No other vaccine has been rolled out this fast.

But we will still need to work together and faster. The virus is mutating, and has evolved into variants from the UK, South Africa and Brazil, which are being closely monitored by health experts. Though vaccination seems to be the best solution in ending the pandemic, it doesn’t mean that the virus will magically disappear.

The Philippines is reported to receive the vaccines by the second quarter of this year. While we all wait for the vaccine rollout in our country, the best thing for us to do is to comply to safety standards.

The Philippine government has basic taglines for the people’s easy recall. Repetition has always been an effective communication tactic. There’s the Department of Public Work and Highway’s Build, Build, Build; and the Department of Agriculture’s Plant, Plant, Plant.

We should all then Comply, Comply, Comply to washing our hands. Comply, Comply, Comply to wearing face masks. Comply, Comply, Comply to maintaining physical distance. Comply, Comply, Comply to answering contact trace forms.

This may be easier said three times than done, but if we want our country to fare better, we must continue fighting the good fight despite quarantine and protocol fatigue. In this global crisis, there is no room for complacency, only repetitive compliance. Whether you’re privileged, careless, or downright indifferent, one thing is clear: the virus does not care.

Each day, over 6 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines are administered in 82 countries. According to Bloomberg, more than 186 million shots have so far been given all over the world.

In the Philippines, the government announced its readiness to launch the vaccination drive, which aims to vaccinate over 90 million adults by the end of 2021. This seeks to attain herd immunity, a situation wherein a considerable percentage of the population becomes immune to the infection, curtailing its spread.

The City Government of Pasig conducted a full simulation of its COVID-19 Vaccination process last February 16. (photo from Pasig City Public Information FB page)

The City Government of Pasig conducted a full simulation of its COVID-19 Vaccination process last February 16. (photo from Pasig City Public Information FB page)

Mock Vaccinations and Dry Runs

To prepare for the vaccines’ arrival, several sectors have been conducting simulations of the vaccination process. Pasig was the first local government unit to have its vaccine plan approved, which met the requirements mapped out by the Department of the Interior and Local Government. This early approval meant that Pasig will be one of the first cities to receive the COVID-19 vaccines once they arrive.

The plan is a detailed outline of the three phases: pre-vaccination, vaccination and post-vaccination. With Pasig planning to vaccinate more than 700,000 residents, all steps—from the registration and floor plan to the process flow and emergency response—were meticulously prepared. Last February 16, the LGU held a complete simulation of the procedure headed by the Pasig City Beat COVID-19 Task Force, Mayor Vico Sotto and the vaccination team. Representatives from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Department of Health (DOH) were present to give their observations on how to improve the process.

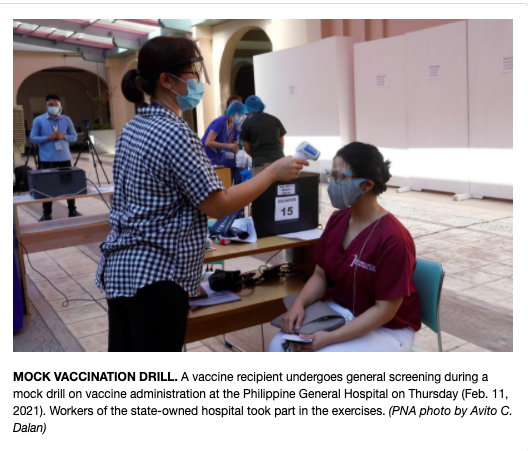

(photo from Philippine News Agency)

(photo from Philippine News Agency)

Hospitals have also been conducting their dry runs, including the Philippine General Hospital (PGH), the country’s biggest COVID-19 referral hospital.

Proud Partner

AIR21 crew loading a refrigerated truck

AIR21 crew loading a refrigerated truck

With over 40 years of experience in various logistics services, AIR21 is proud to be a major partner in the government’s COVID-19 vaccine storage and handling. AIR21 President Maricris Campit shares that for almost 15 years, the company has been servicing the transport and distribution needs of various pharmaceutical businesses nationwide. “The FDA (Food and Drug Administration) granted us a license to operate as a drug wholesaler. We are also certified by WHO to handle pharmaceutical products. Out robust system for shipment tracking and tracing allows us to monitor, not only the progress of nationwide deliveries, but also the temperatures inside the trucks. As the accredited logistics provider of the COMELEC (Commission on Elections) since 2010, AIR21 is able to reach the country’s remote rural areas.”

To ensure the vaccines’ safety and efficacy, they need to be maintained in very low temperatures in every step of the way— from their arrival in the airport to storage and delivery. Campit highlights AIR21’s capability strengthened by the country’s biggest fleet of multi-temperature delivery vehicles. “We have over 100 refrigerated and temperature-control trucks that are Euro 2 and Euro 4-compliant, which means they meet globally-accepted emission standards. These are capable of transporting, not only temperature-sensitive goods like medicines and vaccines, but also medical supplies needed in the vaccination process. All our trucks are equipped with GPS trackers and temperature-monitoring software.”

AIR21’s high performance and customer-driven culture is also boosted by its vast network of dedicated delivery agents nationwide. Aside from meeting various shipping requirements grounded on protocols set by pharmaceutical companies, AIR21 also guarantees on-time deliveries based on the requirements of the national government and local government units.

“On-time delivery ensures the timely administration of the vaccines,” Campit explains. “This seamless delivery is very critical in meeting the vaccination schedules without any untoward incident such as vaccine spoilage that may endanger the public.”

One of AIR21’s cold-storage facilities

One of AIR21’s cold-storage facilities

As the flagship company of OneLGC, AIR21 partners with its affiliates to provide comprehensive services in support of the vaccination drive. These include Nague, Malic, Magnawa, and Associates Customs Brokers (NMM) for customs clearance; U-Freight Philippines for the freight movement from airport to warehouse; Cargohaus and LGC Logistics for the cold-chain storage; Integrated Waste Management Inc. (IWMI) for the collection and proper disposal of medical wastes; and E-Konek Pilipinas for the data information and communications technology.

Because of AIR21’s strong capability and vast resources, the company is invited as partners by competitors in a concerted effort toward pandemic recovery. Campit shares, “We are so proud and excited about this. We feel we are a big player in ensuring that the government fulfills its target in conducting 100% vaccination in the country. The whole team looks forward to giving support to our national government and local government units. It’s a great feeling to be part of this mission.”

Donna May Lina and Agay Llanera

Weeks ago, Australian think-tank group Lowy Institute measured the performance of pandemic responses across the globe. With evaluations based on numbers of reported cases and deaths, tests conducted, and the rates of positive tests, the Philippines ranked 79th on the list.

But the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines may change the landscape of global pandemic recovery. According to Bloomberg, over 152 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines have so far been administered in 73 countries. This is roughly equivalent to 5.64 million doses a day.

With the first batch of COVID-19 vaccines arriving in a few days in the Philippines, health experts agree that the vaccination drive should still be supplemented by basic health and safety measures.

A year after since the Philippines reported its first COVID-19 case, how well do you know the basic precautions that could spell the difference between life and death?

To test your knowledge, go ahead and tick the Yes or No boxes of our COVID-19 Safety Checklist. If your answer is a No, check out the explainer under the Find out How column, which also provides helpful links.

| DO YOU KNOW… | YES | NO |

| 1. Where to get factual information on COVID-19?

| ||

| 2. Know the symptoms of COVID-19?

| ||

| 3. How to wash hands properly?

| ||

| 4. How to wear a face mask?

| ||

| 5. Why staying home is important?

| ||

| 6. What physical distancing is?

| ||

| 7. How to greet people without physical contact?

| ||

| 8. What essentials to put in your bag?

| ||

| 9. How to maximize digital tools?

| ||

| 10. How to work from home?

| ||

| 11. What to do when you had contact with someone with COVID-19?

| ||

| 12. Practice a healthy lifestyle?

| ||

| 13. Why it’s important to be updated daily on community news?

| ||

| 14. How to properly dispose of personal protective equipment?

| ||

| 15. How to ensure your surroundings are clean? |

| FIND OUT… |

| 1. Where to get factual information on COVID-19? It’s alarming to note that until now, there are those who believe that the COVID-19 pandemic is a hoax! Know that the health crisis is real, and that if want to read up more on it, visit these reputable websites: World Health Organization (WHO) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Department of Health (DOH) Get your facts straight on COVID-19 by verifying sources before sharing information on social media.

|

| 2. The symptoms of COVID-19? COVID-19 symptoms range from the most common and less common to the downright serious. Learn to differentiate these from allergy and flu symptoms. People with mild symptoms can manage them at home, but serious symptoms need medical care. Take note that it may take up to 14 days for an infected person to show symptoms.

|

| 3. How to wash hands properly? Washing hands is a basic practice we learned during childhood. Know the proper way of doing it to ensure you’re safe during and beyond the pandemic.

|

| 4. How to wear a face mask? Face masks should cover your nose, mouth and chin. WHO emphasizes the importance of handwashing or hand sanitizing before and after putting on the mask and adjusting it on your face. Here’s the updated “wearing a mask” routine.

|

| 5. Why staying home is important? Because COVID-19 spreads through droplets sneezed or coughed into the air, staying home limits the possibility of you interacting with an infected person. You may also be asymptomatic, so staying home can stop the spread of the virus.

|

| 6. What physical distancing is? When outside the home, keeping a distance of 6 feet between yourself and other people can protect you from infectious droplets. Stay away from crowded places. Practice physical distancing along with other safety measures (masks, avoid touching your face, handwashing, etc.) to reinforce personal protection.

|

| 7. How to greet people without physical contact? Say hello, wave, nod, give an air high-five, a salute, or a flying kiss. There are many ways to greet friends and family while maintaining physical distancing. Perhaps Filipinos followed these safety tips during the holidays, which was why experts noted that a spike in COVID-19 cases was not observed after the Christmas season.

|

| 8. What essentials to put in your bag? Aside from your wallet and cellphone, your bag must contain the following: · Extra face mask · Extra face shield, which you can make from plastic bottles · Alcohol · Sanitizer · Soap · Reusable bottle of water · Towel · Tissue · Your own pen to fill out contact tracing forms (since pens used by other people may contain viruses and bacteria)

|

| 9. How to maximize digital tools? From paying bills to bank transactions and buying essentials, take advantage of online services to keep you safe at home. Last September, the government launched the StaySafe.ph app, the country’s official contact tracing program. Downloading the app also allows you to monitor your health conditions and social distancing practices.

|

| 10. How to work from home? While kids learn from home, you can also learn to work from home if your company allows it. If you’re looking for work, explore remote employment opportunities found in reputable job portals, allowing you to earn from home. In this day and age, learning how to navigate video conferences in different formats is a marketable skill.

|

| 11. What to do when you had contact with someone with COVID-19? Read up on the DOH’s updated guidelines on contact tracing of confirmed COVID-19 cases. Even if you don’t feel symptoms, practice self-quarantine right away. Watch this for more home quarantine tips.

|

| 12. Practice a healthy lifestyle? There are many ways to boost immunity. The basics are incorporating fruits and vegetables in your diet; getting 7 to 8 hours of sleep daily; regular exercise; and maintaining a positive outlook to facilitate your mental health.

|

| 13. Why it’s important to be updated daily on community news? Visit your LGU’s website and follow its social media accounts to know the latest programs you can avail of. Keep track of the active cases in your barangay. Update yourself on your area’s vaccination plans.

|

| 14. How to properly dispose of personal protective equipment? According to WHO, disposable masks should be replaced as soon as they are damp. After removing the used mask without touching its front, immediately throw it in a closed bin and wash hands. To avoid passing on the virus, the UK government recommends putting the used face mask in a plastic bag, and discarding it in another bag dedicated to infectious waste. But environmental advocates warn about how the rampant use of disposables can worsen the climate emergency, which may also have fueled the pandemic. To mitigate waste, some recommend reusable masks, which you can also make.

|

| 15. How to ensure your surroundings are clean? Frequently touched surfaces such as door knobs, light switches, phones and toilets should be cleaned and disinfected regularly. After cleaning these fixtures with detergent and water, disinfect them with this DIY formula. |

With this checklist, we hope you learned something new, or at least remembered what we all need to keep doing. Get these basics down pat, and always comply with safety measures. Even with the arrival of COVID-19 vaccines, we can’t let our guard down. The true key to pandemic recovery lies in awareness, consistency and vigilance.

Donna May Lina with Agay Llanera

It’s been a little over a year since the Philippines reported its first COVID-19 case. Since then, our lives have drastically changed. To reduce the spread of the virus, we all had to learn the basic protocols: wash our hands, wear a mask, maintain physical distance. Guidelines were set out on international, national and barangay levels.

Just a few weeks ago, Lowy Institute, an Australian think-tank group, compared the effectiveness of the different countries’ pandemic responses. Criteria included the numbers of reported cases and deaths, tests conducted, and the rates of positive tests. On the list, the Philippines ranked 79th in terms of COVID-19 performance. Top countries that were able to control the virus were New Zealand (1st), Vietnam (2nd), Taiwan (3rd) and Singapore (13th).

(Source: Lowy Institute)

(Source: Lowy Institute)

What did they do right?

For one, these countries have very clear guidelines. The New Zealand government has created separate COVID-19 safety websites for specific audiences—the business and service sector, workers, and even for its construction industry. Taiwan has only seven pandemic-related deaths because of its tight entry restrictions. As early as February last year, travelers with Taiwanese mobile numbers have been utilizing the QR code system for health declarations. Even home quarantine and isolation monitoring are done via mobile phones; if a person left quarantine, his or her phone will alert authorities who will immediately verify the person’s location.

With clear guidelines come clear penalties. To compare how the Philippines compares with other countries in meting out fines for the simple safety protocol of wearing face masks, Panahon TV came up with this chart:

With local government units in our country having their own penalties, guidelines become confusing especially for travelers. A quick web search on sanctions for those failing to comply with COVID-19 safety protocols also revealed the following:

- New Zealand nips irresponsible behavior in the bud by imposing a fine of NZ$4,000 (₱14,000) for travelers who refuse to test for COVID-19. Violators can be held for 28 days.

- In Vietnam, those who escape quarantine sites, avoid quarantine measures, and fail to complete health declarations face criminal punishment.

- When an OFW left his room at a quarantine hotel in Taiwan for eight seconds, he was fined NT$100,000 (₱172,000).

- Those who fail to comply with Stay-Home Notice requirements in Singapore may be penalized up to S$10,000 (₱360,000) and/or imprisonment of up to six months.

- The farthest the Philippine government has gotten in this area is the mere suggestion of imposing community service and fines for quarantine violators. As of writing, no clear penalties have been drafted.

Factors that Contribute to Pandemic Response

Politics and location play a big role in the different pandemic responses across the globe. Vietnam and Taiwan are known for their disciplined citizens because they have always been challenged by threats of war. Due to geographical reasons, New Zealand has learned to be self-contained. A strict compliance with laws has always been the key component of Singapore’s governance.

Culturally, these countries have a more collectivist culture. Social psychologists define collectivism as a value that emphasizes interconnectedness, prioritizing a society’s goal and needs over those of the individual.

Interestingly enough, countries known for their individualistic cultures seem to have weaker pandemic responses, as listed by the Lowy Institute’s report. These include Sweden (37th), the UK ( 66th), Netherlands (75th) and the U.S. (94th).

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention commentary observes how COVID-19 measures seem to focus more on individual risks, which lead to gaps in response. In order to curtail the global spread of the virus, messaging should promote cultural inclusivity. But instead of pitting one culture type against the other, the commentary suggests embracing “multicentric logics – individual, collective, and everything in between.” Different cultures and attitudes are factors in seeing how countries will be able to implement, comply, and continue to maintain safety guidelines to this date.

(photo by Jire Carreon)

(photo by Jire Carreon)

How will the pandemic end?

In an attempt to answer this question, the New York Times discussed how the 1918 Spanish flu virus, which killed as many as 100 million people worldwide, has simply lost steam, evolving into a still potentially fatal seasonal flu.

With the vaccine race “won” in round one by pharmaceutical companies like Moderna (U.S.) and AstraZeneca (UK), more than 108 million vaccine doses have been administered in 67 countries.

(Source: Bloomberg)

(Source: Bloomberg)

The vaccines were developed through collaborating scientists, were tested among selfless volunteers, and rolled out to countries’ frontliners and vulnerables depending on government strategy. Through modern technology and cooperation, vaccination has been conducted through Emergency Use Authorization, allowing the release of unregistered drugs and vaccines during a public health emergency. No other vaccine has been rolled out this fast.

But we will still need to work together and faster. The virus is mutating, and has evolved into variants from the UK, South Africa and Brazil, which are being closely monitored by health experts. Though vaccination seems to be the best solution in ending the pandemic, it doesn’t mean that the virus will magically disappear.

The Philippines is reported to receive the vaccines by the second quarter of this year. While we all wait for the vaccine rollout in our country, the best thing for us to do is to comply to safety standards.

The Philippine government has basic taglines for the people’s easy recall. Repetition has always been an effective communication tactic. There’s the Department of Public Work and Highway’s Build, Build, Build; and the Department of Agriculture’s Plant, Plant, Plant.

We should all then Comply, Comply, Comply to washing our hands. Comply, Comply, Comply to wearing face masks. Comply, Comply, Comply to maintaining physical distance. Comply, Comply, Comply to answering contact trace forms.

This may be easier said three times than done, but if we want our country to fare better, we must continue fighting the good fight despite quarantine and protocol fatigue. In this global crisis, there is no room for complacency, only repetitive compliance. Whether you’re privileged, careless, or downright indifferent, one thing is clear: the virus does not care.

The pandemic may be 2020’s most significant global event, but a lot more happened in the country this past year. Panahon TV recaps the year that was–from volcanic eruptions and tourism recognitions, to lockdowns and experiencing one of the strongest landfalling tropical cyclones in recorded history.

Let’s take a look back at the events that made 2020 memorable. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XdYNhwm-5c0

The new year is just around the corner, which means most people are making plans and resolutions to spark positive changes in their lives. By letting go of attitudes, habits and situations that no longer serve them, people are better attend to their needs, improving the quality of their lives.

One significant change some make is to literally move beyond their comfort zones—and by that, we mean changing their places of residence. According to a survey released by the Philippine Statistics Authority in 2012, internal migrants were at a whopping 2.9 million between 2005 and 2010. While 45.4% merely changed cities, more than half (50.4%) were long-distance movers who changed provinces. The latter movers came from Calabarzon at 27.7%, the National Capital Region (NCR) at 19.7%, and Central Luzon at 13%.

NCR is the top choice of migrants outside Metro Manila, as shown by the World Bank’s Philippines Urbanization Review in 2017. In the previous decade alone, the country’s annual increase of urban population was at 3.3%, making the Philippines as one of Asia-Pacific’s fastest urbanizing countries.

But what about the second-biggest population of long-distance movers who moved out from NCR? Their significant number shows that there are Filipinos who choose to trade the modern conveniences of city life for the slower-paced rural setting. We get to know some of these brave migrants, and the steps they took to make such a major change.

Layla Tanjutco

Layla Tanjutco

Current residence: Mangatarem, Pangasinan since 2018

Residence history: I was born and raised in Quezon City right up to when I started working in Makati. I eventually had to move away from our childhood home to be nearer my work. I was pretty much the city girl and enjoyed having everything accessible.

In 2007, I decided to try out the probinsya life with my family. We moved to Negros, in a house by the sea. I woke up to and was lulled to sleep by the sound of the waves— and I loved it. After about a year, I got pregnant with my second child. Just then, job offers in Manila started coming in, so I decided to move back to the city. My family followed, and we settled back in my childhood neighborhood.

Reason for moving to Pangasinan: I’ve been working from home full time. Meanwhile, my favorite cousin put up a farm in their family property in Pangasinan. My family and I would go for short visits and I would always enjoy my time there. My cousin needed help running the farm, and one of my sisters and I were getting really tired of the city life so we floated around the idea of moving to the farm for months before finally deciding.

Also, my kids were growing up and needed their own space. I needed my own space too and with how multi-bedroom rentals are in Manila, there was no way I could afford them. That and the fact that my sister and I can work anywhere as long as we have internet cemented our idea for the move.

Liwliwa Malabed

Liwliwa Malabed

Current residence: Bae, Laguna since 2016

Residence of history: I was born and raised in Ilocos Sur, and went to Manila to study in UP Diliman in 1997. Since then, I never left the campus, staying in dorms and rentals even after I graduated and took my master’s degree. When I became pregnant with my daughter, our family moved to Makati, and when we needed more space, we relocated back in Quezon City.

Reason for moving: I was coming home from a workshop I’d conducted near ABS-CBN. It was raining on a Friday before a holiday payday. I couldn’t get a cab or a free seat in jeepneys. My daughter was only a year old then, and in my desperation to go home, I started walking, hoping I could catch transportation along the way. But I only got inside a jeepney in Quezon City Circle, and even then, the vehicles weren’t moving. So I got off and ended up walking all the way to our house in Visayas Avenue, Quezon City. It was then I told my partner that we should move out of Manila.

We chose Laguna because my partner wanted to live somewhere near Manila. Because I’m a licensed teacher, I felt I could find a job anywhere. I also liked Laguna because I had fond memories of it—it was there I finished a part of my master’s thesis, and my older brother has been living in Los Baños since 2008. Knowing he was there was a huge plus because I knew I could count on him if we needed help.

Aya Tejido

Aya Tejido

Current residence: Antipolo, Rizal since 2009

Residence history: I have always been a Manila girl until I got married and moved to the borderline of Cainta and Antipolo in Rizal.

Reason for moving: My in-laws bought this house in the 1980s, and since it wasn’t being used, they suggested that we renovate it and live in it. My husband and I agreed because we didn’t have to pay rent. It didn’t occur to us that we would be far from everyone; we just wanted to have our own space without incurring so much cost.

Layla about to harvest vegetables in the farm

Layla about to harvest vegetables in the farm

What are pros of probinsya living?

Layla: I sometimes miss not having everything at the drop of a hat or being far away from my friends, but waking up to bird song or seeing the night sky peppered with stars, feeling closer to the earth and things that grow are things that I cherish and am very grateful for. Anywhere you live, there will be challenges, but I feel like my soul is calmer here. My sister and I would often joke that we’re having an eternal summer vacation. We used to just spend short vacations here; now, we live here and we love it no less, maybe even more.

Liwliwa: We enjoy each other as a family. Before the pandemic, we’d often hang out at IRRI (International Rice Research Institute) and UPLB (University of the Philippines Los Baños). The air is fresher, and we get to see fireflies. We like exploring other parts of Laguna; we’ve gone camping in Cavinti and Caliraya. Our diet has become healthier because we directly source from local farmers. I think it’s more peaceful and safer here, and the rent is much cheaper. Right now, we live in a 4-bedroom house with two bathrooms and a backyard—and the rent is a fraction of what we’d pay in Manila with the same facilities.

Aya: It’s less dusty here. In Manila, it would take only two days to get a thick film of dust in your room. Back when we didn’t have neighbors, we could see the mountain, which looked dramatic during sunrise. Even when it’s summer, we don’t feel the heat. Over the years, the area has gotten more developed, with more small hospitals and community malls with groceries, so it’s now convenient to live here.

Liwliwa and her daughter at the Makiling Botanic Gardens

Liwliwa and her daughter at the Makiling Botanic Gardens

What are the cons of probinsya living?

Layla: What we really found challenging to adjust to at first was the early time shops would close. In Manila, restaurants, bars and stores would be open late at night. Here, only 7-11 and the evening pop-up carinderias would be open beyond 8 p.m. During the pandemic, closing times became even earlier, and a lot of the small shops and eateries closed down for good. We didn’t use to have delivery services for the various cafes and restaurants that started popping up early last year, but now we do. We often had power outages and I never thought I’d consider owning a generator but here we are.

Liwliwa: To get to Los Baños, which is where all the action is, you take a jeepney that has to be full before it leaves the terminal. So even if we’re near Los Baños, travel time takes about an hour. Public transportation is a real challenge, especially when I get home late from the occasional gig in Manila. When that happens, I’d call my brother, who’d fetch me with his motorcycle. Eventually, my partner and I were able to buy a car, which allowed us to move around during lockdown.

Aya: I had to get used to the silence. As early as 4 a.m. in Manila, I’d hear jeepneys warming up their engines. Noise was a constant companion, even at night. Here, I only hear birds and the tuko. I found it weird at first.

In my area, traffic is a perennial issue because there’s only one road to take if you want to go to the city—and that’s the Marcos Highway. The problem is compounded when there’s roadwork along the highway. If we’re traveling out of the country, we have to book a hotel near the airport because there’s no way we can leave at a decent hour and arrive in time for our flight.

Mostly retirees live in our huge village, so one time, when my daughter was looking for playmates, we had to walk several streets before we found kids her age.

Aya in her backyard with a flourishing malunggay plant behind her.

Aya in her backyard with a flourishing malunggay plant behind her.

Are you happy with your decision to move?

Aya: We’re happy living here. If someone asked me advice about moving out of Manila, I’d tell them to always look for the nearest hospital, drugstore and grocery store. Since they would be living away from family, they need to know where to get their essential goods and services. Here, we learned to be self-reliant, especially when there’s flood. Our shelves have to be well- stocked all the time. Still, it’s more refreshing to live outside the city.

Liwliwa: When we made the decision to live in Laguna, I was ready for countryside living. I think we always idealize the province as a good place to bring up our families, but what matters more than the place is the people you’re be living with. I think our family will thrive wherever we end up because we get along with each other.

Layla: Living the probinsya life really drove home for me how we take many things in our life for granted. Whether you’re living in the city with the many conveniences that are easily accessible or here in the laid-back province, you don’t know what you have until it’s gone. We always feel like we’re missing something; we want what we don’t have, so much so that we forget what we do have at this moment. I am thankful I have the luxury of looking out my window and saying hello to a beautiful bird, or eating sweet, seedless papaya from our backyard tree in the same way I am thankful now for the many years I spent in the city, and eventually (when things are better) being able to go back there for a quick visit to see friends and the places I missed. Probinsya life really teaches you to slow down, take in as much of the view as you can, enjoy the little things every day, and be thankful for each one.

Among the total number of overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) pegged at 2.2 million by the Philippine Statistics Authority in 2019, over 300,000 have so far been repatriated by the Department of Foreign Affairs because of pandemic-disrupted economies. Though this was deemed as the “biggest repatriation effort in the history of the DFA and of the Philippines” by Foreign Affairs Undersecretary for Migrant Workers’ Affairs Sarah Lou Arriola, the numbers indicate that majority of OFWs still remain in other countries.

Recent events have created stress for OFWs, who have their own struggles even without the health crisis. Psychologist Roselle G. Teodosio, owner of IntegraVita Wellness Center, explains that the OFWs’ primary source of stress is being away from their families. “The OFWs usually worry about the families they leave behind. This is especially true for those who have spouses and children. Another stressor is the culture shock or how to cope with the daily grind of living in a foreign land. The language barrier is a major stressor for OFWs aside from adapting to the new culture.” Financial obligations also create pressure as families and relatives tend to think OFWs make lot of money. “The family and relatives do not realize the sacrifices and hardships the OFW makes to be able to send money. Another stressor is their employers and co-workers. An abusive employer is not uncommon, and there may be multiracial co-workers. Different cultures tend to clash and lead to conflicts at the workplace.”

With the pandemic affecting economies and causing people to lose jobs, OFWs may be overwhelmed by multiple pressing problems. “There is fear, not only for the OFWs’ health, but also for the families dependent on them. Knowing that there is a greater risk for their families back home, there will be greater pressure on OFWs to retain their jobs,” says Teodosio. “There is the fear of a family member contracting the virus. The inability to be at the bedside of the sick family member will weigh heavily on the OFW. Also, the fear for one’s own health in a foreign land can be daunting. The OFW has to stay strong and not show the family back home that he is really scared since he thinks this will add to his family’s worries.”

As if these complications weren’t enough, now the holiday factor is thrown into the stressful mix. Because of the pandemic, OFWs who normally go home at this time to celebrate Chrismas with their families are forced to stay in their countries of employment. “Even the families of the OFWs feel the fear of their loved ones contracting the virus abroad or if they force themselves to come home. Another concern is if they go home, will they be able to go back to their jobs? So to make sure that there is a semblance of the security of tenure, then the OFW will remain where he is and not try to go back. The risk of getting infected is much higher if the OFW will try to come home,” shares Teodosio.

Christmas away from Family

Agnes, who has been working in Taipei for almost 5 years, comes home once a year during the holiday season. Like most Filipinos, she regards Christmas as the time to be with family. “My siblings and I are all working professionals, and Christmas is the best time to be in the same place altogether, as we usually take a two-week vacation leave from work. I spend most of my December with family, and since we’ve had a baby in the family—my younger brother’s— it’s been a lot more fun and special.”

Agnes admits that this is her second time to skip spending Christmas with her family. “Last year, I had to go to Italy for the wake of my fiance’s mom. I didn’t feel the impact of not being with my family on this important holiday because I was in a different country, and also needed to support my fiance and pay my respects. But this year, I’m definitely feeling the impact.”

Husband-and-wife OFWs Armie and Boyet in Qatar

Husband-and-wife OFWs Armie and Boyet in Qatar

Because of the nature of their jobs, Armie and Boyet who have been working in Qatar for 9 years don’t really get to go home during the holiday season. “That’s a busy time in the office,” shares Armie. “So we go home usually in April or May. But we didn’t get to do that this year because of the pandemic. So we thought we’d go home in December for a change—but that plan fell through as well.”

Still, spending Christmas away from her children and her 80-year-old mom for almost a decade has taken a toll on Armie. “It gets sadder each year. Sometimes, I hear a piece of music that reminds me of home, and already, I get emotional. There’s this deep longing to have our family together. When my husband and I first arrived here, we missed our family, but there was the novelty of discovering a new place and culture. Now, we just simply miss our family.”

Armie with her daughter and her 80-year-old mom

Armie with her daughter and her 80-year-old mom

Increased Anxiety and Worry

Affirming what Teodosio mentioned, Agnes confesses the stress and anxiety she experiences at work is compounded by the pandemic. “I know I have the choice to not tune in to the news, but I always worry about the effects of the government’s ineptitude on my family and loved ones. I sometimes think I may be getting too emotional and overreacting, but I’ve been feeling like this for quite a while. It’s hard to be in a different country with no support system.”

Even if she’s able to go home, Agnes would rather stay in Taiwan for several reasons. “Although my host country has handled the pandemic well, no one knows if you’ll be able to contract the virus in transit. I don’t have enough leave credits to do a long-period quarantine, and I certainly don’t want to spend Christmas in quarantine.” Though her family understands her decision, Agnes can’t help getting emotional. “The knowledge that I can’t be with my family on this important holiday is making me feel depressed. We sometimes have video chats and I’ve brought up the topic of missing them a lot especially in these stressful times, and they’ve been supportive to a certain extent. Nevertheless, it’s still a painful decision even if it’s a necessary one.”

Armie and Boyet with their kids in 2018

Armie and Boyet with their kids in 2018

Though Armie worries about her family contracting the disease, a temporary setback came in the form of her husband’s 5-month unemployment. “He works in a gym, which shut down during the pandemic. The gym is back in business now, but during those 5 months, I worried about making ends meet. Somehow, we did it by cutting back on expenses.”

November brought Typhoon Ulysses, which submerged their house in Bulacan. “My kids and my mom didn’t have electricity and drinking water for several days. I asked help from friends in the Philippines, who thankfully helped them out. Now, my kids are busy with house repairs.” Though her children are used to Armie and Boyet’s absence, Armie confesses that her heart broke when her husband asked them what else they needed. “My kids replied, ‘You. We need you both. Please come home.”’

Coping this Holiday Season

The combined challenges of the pandemic and the holiday season may be difficult, but they can be conquered. Our interviewees offer these tips:

Stay grounded. “OFWs need to be resilient during these trying times. Focus on the things that they can control such as their thoughts, emotions, reactions and behavior. So in a time of pandemic, they can do their part in keeping safe by following safety protocols,” says Teodosio.

Find a support group. While taking a leave from work to “unplug from the stress,” Agnes is going to meet up with Pinoy friends in Taiwan. “We’re planning to have Noche Buena together and watch the fireworks display on New Year’s Eve.”

Stay healthy. Agnes tries to cope by taking care of herself physically and mentally. She adds, “So when it’s safe to travel, I’ll be in a better state and be able to make up for lost time.” Teodosio advises OFWs to differentiate between good and bad anxiety. “Some anxiety may be productive; this is what makes us wash our hands often and socially distance ourselves from others and keep our masks on,” she explains.

Focus on the present. The OFW needs to take one day at a time. “Excessively worrying about the future for himself or his family can sometimes paralyze a person with fear,” says Teodosio. “Becoming aware and mindful of all his thoughts and feelings can be very helpful in managing these emotions.”

Connect with family. Armie and Boyet make it a point to virtually share the annual Noche Buena with their family. “I plan their meal, take care of the budget, and make sure they decorate the house. When midnight strikes, Boyet and I eat with them via video chat,” shares Armie. Teodosio encourages OFWS to maintain constant communication. “Trying to weigh the pros and cons of coming home can help the OFW and their loved ones in understanding what is more important to them—the health of the OFW or being together during Christmas. Having the patience for one another and thinking of what is best for everyone will help the families cope in these trying times.” Agnes affirms this: “Sometimes I feel helpless, but at least with the chats and messages, there’s still something I can do even if it’s a small thing.”

If you’re anxious or depressed, don’t hesitate to reach out to the following:

- Roselle Teodosio (psychologist) – 09166961223 and 09088761223 or email: selteodosio@gmail.com

- National Center for Mental Health Crisis – 09178998727

- Philippine Mental Health Association – 09175652036

- Philippine Psychiatric Association – 09189424864

Just after midnight on August 17, 1976, a magnitude 8 earthquake shook the areas around Moro Gulf in Mindanao, including Cotabato City. But the disaster did not stop there; less than 5 minutes later, a tsunami as high as 9 meters roared and swallowed 700 kilometers of coastline. When the sea ebbed to its peaceful state, around 8,000 had died from the combined effects of the earthquake and tsunami, with the latter accounting for 85% of deaths and 95% of those missing and never found. The event, now known as the 1976 Moro Gulf Earthquake, is recognized as the deadliest earthquake that ever hit the country.

Devastation of the 1976 tsunami at Barangay Tibpuan in Lebak, Mindanao (Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Devastation of the 1976 tsunami at Barangay Tibpuan in Lebak, Mindanao (Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Almost two decades later on November 15, 1994, Mindoro was rocked by a magnitude 7.1 earthquake. Like what happened in Mindanao, majority of the 78 casualties of the Mindoro earthquake was due to the 8-meter high tsunami that occurred 5 minutes after the quake.

The truth is, though Filipinos are aware of devastating tsunami happening in other countries like Japan and Indonesia, they do not often associate these natural disasters in their homeland. But as past events indicate, deadly tsunami can occur locally. As Undersecretary of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) for Disaster Risk Reduction-Climate Change Adaptation (DRR-CCA) and Officer-In-Charge of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) put it, “Tsunami are very fast in the Philippines and we need to prepare for them.”

Tsunami 101

In observance of World Tsunami Awareness Day last November 5, PHIVOLCS organized an online press conference to spread the word about tsunami. Mostly generated by under-the-sea earthquakes, tsunami are characterized by a series of waves with heights of more than 5 meters. According to Solidum, such earthquakes can be triggered by underwater landslides, volcanic eruptions, and the more unlikely meteor impacts. These cause the seafloor to lift, causing the water it carries to rise.

There are two types of tsunami—the distant and local. Distant or far-field tsunami is generated outside the Philippines, mainly from countries bordering the Pacific Ocean like Chile, Alaska (U.S.) and Japan. With these events being monitored by The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC), the Philippines has 1 to 24 hours of preparation before the tsunami’s arrival, depending on its origin.

But with local tsunami, lead time is cut down to a mere 2 to 10 minutes after the earthquake. “Preparedness is very important because rapid response is needed for locally-generated tsunami. The trenches are where the large earthquakes and tsunami can be generated, and we are only the country wherein trenches can be found on both sides. Hence, both sides of the country need to prepare for tsunami. Aside from that, the eastern side of the country faces the Pacific Ocean or the Pacific Ring of Fire where earthquakes and tsunami can also be generated,” said Solidum.

What PHIVOLCS is doing

Part of the Tsunami Risk Reduction Program of PHIVOLCS are the Tsunami Hazard Mapping and Modeling, and the Tsunami Hazard Risk Assessment, both of which aim to understand tsunami, manage their hazards and risks, and identify priority actions for response and recovery. To detect possible tsunami, PHIVOLCS set up its Monitoring and Detection Networks Development.

Aside from the 107 seismic stations that receive data for earthquakes and tsunami, there are also 29 real-time tide gauges all over the country. Through the hazards and risk-assessment software code REDAS, PHIVOLCS can evaluate potential earthquake hazards, create tsunami simulations, and predicting the number of affected people. “The total population exposed to tsunami would be close to 14 million,” said Solidum. “But they will not be affected at the same time. It would depend on where the tsunami would occur. In NCR, for example, the prone population would be around 2.4 million. And the next highest would be 1.6 million in Region VII, 1.2 million in Region VI— and in Region IXA, around 1 million.”

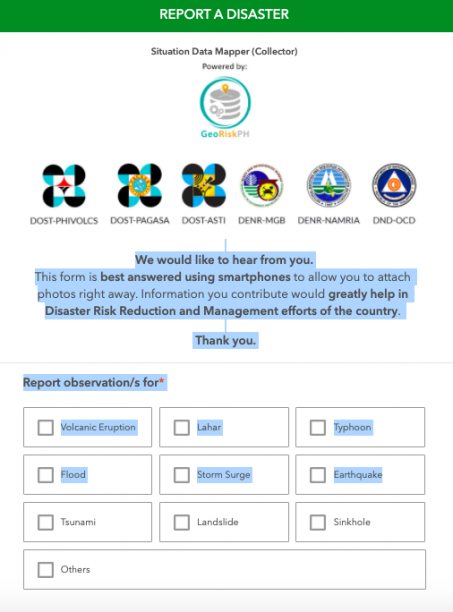

Meanwhile, HazardHunter Philippines, which is open for public use, can assess hazards depending on the user’s specific location. “HazardHunter can also give you a more detailed tsunami hazards assessment because it can provide you a map showing the different areas that will be affected by different tsunami heights. It is color coded, indicating areas prone to various tsunami heights.” Solidum appealed to the public to take advantage of the “Report a Disaster” website. Here, people can post pictures and videos of current risks and hazards in their areas, and describe disasters impacts, which can help the government’s risk and impact assessments.

Screencap of “Report a Disaster” website

Screencap of “Report a Disaster” website

“In the Philippines, we use a simple tsunami information or warning scheme,” explained Solidum. “We will evacuate once the tsunami information is categorized as a tsunami warning. We expect a destructive tsunami of more than 1 meter and this would need immediate evacuation of coastal areas. Boats at sea are advised to say offshore — in deep waters.”

Shake, drop and roar

Because local tsunami can be very fast, people need to know its natural signs:

Shake – refers to a strong earthquake.

Drop – refers to the sea level receding fast.

Roar – refers to the unusual sound of the returning wave, which indicates a tsunami.

After an earthquake, Solidum recommends for people near the shore to immediately move to elevated ground inland, or take refuge in tall and strong buildings. “If they have not moved at all, once they hear the tsunami and there are unusual sounds, there might not be enough time. They really need to respond immediately,” warned Solidum.

PHIVOLCS also released tsunami safety and preparedness measures on their website:

- Do not stay in low-lying coastal areas after a felt earthquake. Move to higher grounds immediately.

2. If unusual sea conditions like rapid lowering of sea level are observed, immediately move toward high grounds.

3. Never go down the beach to watch for a tsunami. When you see the wave, you are too close to escape it.

4. During the retreat of sea level, interesting sights are often revealed. Fishes may be stranded on dry land thereby attracting people to collect them. Also sandbars and coral flats may be exposed. These scenes tempt people to flock to the shoreline thereby increasing the number of people at risk.

Solidum stressed the importance of community-based preparedness, built on planning and drills to create the following output:

- development of evacuation plans based on the hazard maps

- installation of different types of signage (signage for hazards, signage for the evacuation area, signage for the directions to go to the evacuation area)

- conducting of seminars and lectures

- drills

Tsunami preparedness during COVID-19

The devastation of several typhoons this year, coupled with the country’s location in the Pacific Ring of Fire, are proof that the Philippines is prone to various hazards. Because of the

COVID-19 pandemic, Solidum admitted that PHIVOLCS had to rethink their training methods. “Before, we actually go down to various coastal communities and conduct lectures in the evening, so that people who worked in the daytime can also attend. But the pandemic has enabled more people to listen because of the social media platform and our webinars. We’ve reached more people in terms of information campaign. But we hope that local government disaster managers will do the actual preparedness at the community level.”

Solidum noted that though COVID-19 continues to cause loss of lives and the disruption of public services, mobility and economic development, tsunami can create far more devastating impacts. “We will see the physical impacts through buildings, infrastructures, property, water supply pipes, electrical supply, communication system, roads, bridges, and ports. This is in addition to the physical impact on people because of the collapsing houses or the impact of the large volume of water. We have science, technology, and innovation from DOST that can help in preparedness and disaster risk reduction. We need to use it, but we need to share this information to the communities and the public,” he ended.

Watch the full press conference from PHIVOLCS.

Watch Panahon TV’s primer on tsunami.

In an effort to “build a kinder and more compassionate world,” the World Kindness Movement observes World Kindness Day on November 13 every year. It is “a day set aside to celebrate and appreciate kindness around the world.”

But how does one define kindness? This pandemic, simple acts of kindness like staying home and wearing a face mask can do a lot in curtailing the spread of the virus. Kindness can also mean getting to know something or someone beyond the general bias toward it—such as Wuhan City in Central China, which people all over the world now only know as the starting point of COVID-19. This World Kindness Day, we offer a different, kinder view of Hubei Province’s capital city.

It was once China’s capital.

From December 1926 to September 1927, Wuhan was the capital of the Kuomintang nationalist government. To create the new capital, China’s nationalist authorities merged the cities of Wuchang, Hankou, and Hanyang, from which Wuhan’s name was derived. However, the city lost its capital status when Chiang Kai-Shek established a new government in Nanjing.

It is directly related to the fall of Chinese monarchy.

The Wuhan Uprising in 1911 ended China’s last imperial dynasty, the Qing Dynasty. The success of the revolution prompted other provinces to follow, and in 1912, 18 more provinces united to form the Republic of China. The abdication of the Qing Dynasty the following month marked the end of the kingdom.

![]()

It is one of the world’s largest university towns and is a center for research.

With over one million students in 53 universities, Wuhan is considered one of the largest university towns in the world. It has 4 scientific and technological development parks, over 350 research institutes, and 1,656 high-tech enterprises.

It is referred to as the “Chicago of China.”

Chicago is a hub of transportation, which includes O’Hare, the most globally-connected airport in the US. Wuhan is similar in a sense that it offers transport to almost all parts of China. It is a center for ships and railways, with the Wuhan Railway Hub offering trips to major cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Harbin, Chongqing, and Guangzhou.

Mulan probably lived in Wuhan.

Some theories state that Hua Mulan, the legendary female warrior and well-known “Disney Princess,” lived in the Huangpi District of Wuhan. Some even say that it is her birthplace.

Famous Places

Wuhan is a popular tourist destination with centuries-old attractions full of history, culture and astounding views.

![]()

Yellow Crane Tower

The Yellow Crane Tower was built in 223 as a watchtower for King Sun Quan’s army. The tower was destroyed and rebuilt seven times during the Ming (1368 – 1644) and Qing (1644 – 1911) Dynasties, and in 1884, it was completely destroyed in a fire.

Rebuilt in 1981, the Yellow Crane Tower stands 51.4 meters tall and consists of five floors. Interestingly, it appears the same regardless of the direction it is viewed from. Not only is it one of the most prominent towers in the south of the Yangtze River, it is also the symbol of Wuhan due to its cultural significance.

Hubu Alley

Built in 1368, Hubu Alley is known as “the First Alley for Chinese Snacks”, and has since been serving traditional Chinese breakfasts, such as hot dry noodles, beef noodles, Chinese doughnuts, and soup dumplings. From the Yellow Crane Tower, it can be reached 20 minutes by foot.

![]()

East Lake Scenic Area

The East Lake can be found on the Yangtze River’s south bank and in Wuchang’s east suburb. Covering an area of 87 square kilometers, it is the largest lake within a Chinese city. The area is “formed from many famous scenic spots along the bank,” and attracts many tourists due to its scenery.

Well-known Food and Dishes

Wuhan’s local food is said to be a mix of the cuisines of Sichuan, Chongqing, and Shanghai, which make it “spicy yet full of flavor.” Here are three of its most famous eats:

Hot Dry Noodles (Reganmian)

This is Wuhan’s most famous dish and the first one that locals will mention. The dish, which is essentially “dry noodles mixed with sesame paste, shallots and spicy seasoning,” is eaten for breakfast and as a snack.

![]()

Doupi

Often sold as a street snack, doupi’s layers are either made of tofu skin or “pancake lookalikes”. Glutinous rice is combined with usually no more than three ingredients chosen from beef, egg, mushrooms, beans, pork, or bamboo shoots stuffed in between the layers. Once everything is assembled, doupi is pan-fried, making it crispy on the outside and soft in the inside.

Mianwo

Though donut-shaped, mianwo is salty—made of rice milk, soybean milk, scallions and salt.

Wuhan’s Downside

Even with its must-see scenery and mouth-watering dishes, Wuhan, just like any other place, is not perfect.

Crowds and traffic jam

With a population of around 11 million, Wuhan has the densest population in Central China and is the 9th most populous city in the country. Large crowds, traffic congestions, and long lines are unavoidable in the city.

Before the East Lake became the picturesque spot that it is today, it suffered from soil, water, noise, and air pollution for decades. Wuhan used to be a major manufacturing site, causing the lake’s water quality to be very poor, with outbreaks of blue-green algae and dead fish. However, through the years, its water quality has dramatically improved. Because of this, East Lake is now able to host swimming contests, and serves as one of the best attractions in the city.

Waste concerns

In 2019, street protests were carried out in Yangluo of the Xinzhou District by around 10,000 local residents rallying against the construction of the Chenjiachong waste-to-energy plant – an incinerator that the government planned to construct to handle the city’s waste. But the incinerator was said to emit cancer-inducing toxins, and was going to be built only 800 meters away from residences.

The Xinzhou District government tried to calm protesters down by assuring them that their voices will be heard in the decision-making process. However, reports said that government officials and the police went door-to-door to force residents to sign the project’s consent form, threatening them if they refused to do so.

From its cultural and historical prominence to its contributions to technological innovation, there is clearly more to Wuhan than just the coronavirus. Like any other city, it has its strengths and imperfections worth learning about especially during the pandemic and World Kindness Day.