Last October 2, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) released a La Niña Advisory, announcing the onset of above-normal rainfall conditions in the country.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), La Niña is a “cold event” that pertains to “below-average sea surface temperatures across the east-central Equatorial Pacific.” Analiza Solis, chief of PAGASA’s Climate Impact Monitoring and Prediction Section stated that the weak habagat (southwest monsoon) experienced from June to September this year was indicative of an impending La Niña. “Historically, below-normal rainfall conditions in areas under the Type 1 Climate (western parts of Luzon, Mindoro, Negros and Palawan) during the habagat season is a precursor or part of the early impacts of La Niña.”

Though “weak and moderate La Niña” is expected to persist until March 2021, PAGASA Administrator Dr. Vicente Malano warned to never underestimate its possible effects. “In 2006, Guinsaugon in Leyte experienced a massive landslide. It caused considerable damage in properties and deaths.” The disaster was believed to be triggered by an earthquake in Southern Leyte, and two weeks of non-stop rains induced by weak La Niña. The landslide buried around 980 of the village’s population of 1,857.

What to expect

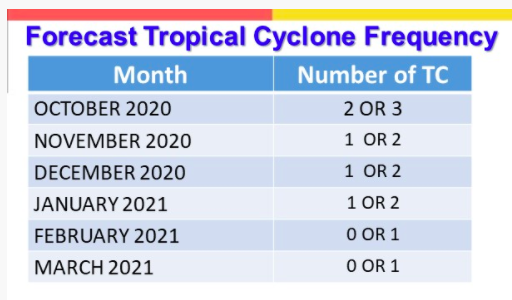

The approaching amihan (northeast monsoon) is expected to enhance La Niña. Solis explained that the rainfall forecast for October this year until the first quarter of 2021 is 81 to 120% more than the normal. Areas most likely to be affected are MIMAROPA (Mindoro, Marinduque, Romblon, and Palawan), Visayas and Mindanao. Because of the 2006 landslide, PAGASA is also closely monitoring western Luzon, even if it is normally dry during La Niña. “Day-to-day forecasts are crucial, supported by tropical cyclone warnings and sub-seasonal forecasts, so we can prepare for possible extreme weather and rainfall events,” Solis said, adding that this La Niña, five to eight cyclones are expected until March 2021.

(source: PAGASA)

(source: PAGASA)

Preparing for Possible Outcomes

According to Dr. Renato U. Solidum, Jr., the undersecretary for Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate, various agencies should focus on Disaster Risk Reduction Management (DRRM). “First, we need to monitor the different weather and climate phenomena, which PAGASA is doing. Second is assessing hazards and risks, which involves identifying the risks, their effects and the affected areas. Third is disseminating information and warnings to different sectors through proper communication channels. And fourth—the most important of all—is to have an effective and efficient response.” This includes mitigation measures, their effectivity, and a quick response that will lead to quick recovery.

Impact on Agriculture

Solis stated that during La Niña, low-lying agricultural lands are prone to floods, which may produce extensive crop damage. Recurring rains also increase the possibility of pests and crop disease, and may lead to river flooding and dam spillage.

Impact on Health

During excessive rainfall, there is a prevalence of waterborne diseases such as cholera and leptospirosis in flooded areas—things we need to avoid, along with loss of lives from flashfloods.

Impact on Environment

Landslides and mudslides are possible, while coastal communities are warned against coastal erosions due to strong waves. In the urban setting, damage to infrastructures is possible, as well as urban flooding, economic losses, and increased traffic.

Angat Dam located in Bulacan (file photo)

Angat Dam located in Bulacan (file photo)

Filling our Dams

The water level in Angat Dam, which supplies 97% of Metro Manila’s water needs, has been slowly but continuously decreasing. “These past weeks, we’ve seen a decline in Angat, Pantabangan and other dams. Even if it rains in these areas, they don’t hit our reservoirs,” Dr. Malano reported. But because of the rainfall forecast during La Niña , our dams are expected to recover. Weather Services Chief Roy Badilla of PAGASA’s Hydrometeorology Division stressed this benefit of La Niña: “50% of our rainfall come from tropical cyclones and La Niña, so without the La Niña, our dams won’t have enough water.”

Solis encouraged the public to maximize rain water harvesting and storage to cope with the dry season from April to June. Flood warnings and advisories from PAGASA should also be monitored. To avoid floods, the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) is requested to remove road obstructions. As local government units and disaster risk reduction offices prepare for imminent disasters, farmers need to strengthen their post-harvest facilities to ensure the proper drying and storage of their produce. “Adverse impacts are likely over the vulnerable areas and sectors of the country,” Solis added. “While our dams have their fill of rain, we should mitigate the possible impacts of La Niña and the amihan.”

La Niña and the Pandemic

Though La Niña is a natural climate variability, Solis said that climate change might also be affecting its pattern. “Before the year 2000, strong El Niño and La Niña episodes occur at least every 7 to 10 years. But during the past decades, the intervals have been cut down to 5 to 7 years. Along with their increased frequency is the increased intensity of their impacts.”

Because this year’s La Niña is coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic, PAGASA’s OIC-Deputy Administrator for Research and Development Esperanza Cayanan emphasized the need for preparedness in evacuation centers. “We need to enforce physical distancing among evacuees, and make sure that these centers are not used for COVID-19 patients.” Solis mentioned the same concern for hospitals. “Health care centers and hospitals should prepare for additional patients with water-borne diseases, and to separate them from COVID-19 patients.”

In the meantime, Dr. Malano suggested the use of schools and churches, now empty because of the prohibition of mass gatherings and face-to-face classes. “Disaster risk reduction should be everyone’s responsibility. We need to cooperate with each other so we can open up these facilities for evacuees, allowing them to observe physical distancing.”

Despite the warm air of El Niño, colder days are expected in the coming weeks.

According to PAGASA, the country is currently in the transition period. But what does this mean?

Transition period is a phase where masses of cold and dry air and warm, humid air meet. This point is called the frontal system, which normally brings rain showers.

PAGASA Weather Forecaster Chris Perez states that the cold front is usually the precursor of the amihan or northeast monsoon. When the tail end of a cold front affects Luzon or Visayas areas, this means that the northeast monsoon is slowly affecting the Extreme Northern Luzon, and will eventually move southward.

The onset of northeast monsoon will happen somewhere between the last week of October and the first week of November, and will peak in the month of either January or February.

Amihan is responsible for lower temperatures, characterized by cold and dry air coming from Mainland China. During amihan season, cirrus clouds dominate the sky, bringing good weather. Compared to the southwest monsoon season, fewer thunderstorms are likely to happen during this season.

Last year, the onset of amihan was declared on October 16, 2014.