Just after midnight on August 17, 1976, a magnitude 8 earthquake shook the areas around Moro Gulf in Mindanao, including Cotabato City. But the disaster did not stop there; less than 5 minutes later, a tsunami as high as 9 meters roared and swallowed 700 kilometers of coastline. When the sea ebbed to its peaceful state, around 8,000 had died from the combined effects of the earthquake and tsunami, with the latter accounting for 85% of deaths and 95% of those missing and never found. The event, now known as the 1976 Moro Gulf Earthquake, is recognized as the deadliest earthquake that ever hit the country.

Devastation of the 1976 tsunami at Barangay Tibpuan in Lebak, Mindanao (Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Devastation of the 1976 tsunami at Barangay Tibpuan in Lebak, Mindanao (Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Almost two decades later on November 15, 1994, Mindoro was rocked by a magnitude 7.1 earthquake. Like what happened in Mindanao, majority of the 78 casualties of the Mindoro earthquake was due to the 8-meter high tsunami that occurred 5 minutes after the quake.

The truth is, though Filipinos are aware of devastating tsunami happening in other countries like Japan and Indonesia, they do not often associate these natural disasters in their homeland. But as past events indicate, deadly tsunami can occur locally. As Undersecretary of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) for Disaster Risk Reduction-Climate Change Adaptation (DRR-CCA) and Officer-In-Charge of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) put it, “Tsunami are very fast in the Philippines and we need to prepare for them.”

Tsunami 101

In observance of World Tsunami Awareness Day last November 5, PHIVOLCS organized an online press conference to spread the word about tsunami. Mostly generated by under-the-sea earthquakes, tsunami are characterized by a series of waves with heights of more than 5 meters. According to Solidum, such earthquakes can be triggered by underwater landslides, volcanic eruptions, and the more unlikely meteor impacts. These cause the seafloor to lift, causing the water it carries to rise.

There are two types of tsunami—the distant and local. Distant or far-field tsunami is generated outside the Philippines, mainly from countries bordering the Pacific Ocean like Chile, Alaska (U.S.) and Japan. With these events being monitored by The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC), the Philippines has 1 to 24 hours of preparation before the tsunami’s arrival, depending on its origin.

But with local tsunami, lead time is cut down to a mere 2 to 10 minutes after the earthquake. “Preparedness is very important because rapid response is needed for locally-generated tsunami. The trenches are where the large earthquakes and tsunami can be generated, and we are only the country wherein trenches can be found on both sides. Hence, both sides of the country need to prepare for tsunami. Aside from that, the eastern side of the country faces the Pacific Ocean or the Pacific Ring of Fire where earthquakes and tsunami can also be generated,” said Solidum.

What PHIVOLCS is doing

Part of the Tsunami Risk Reduction Program of PHIVOLCS are the Tsunami Hazard Mapping and Modeling, and the Tsunami Hazard Risk Assessment, both of which aim to understand tsunami, manage their hazards and risks, and identify priority actions for response and recovery. To detect possible tsunami, PHIVOLCS set up its Monitoring and Detection Networks Development.

Aside from the 107 seismic stations that receive data for earthquakes and tsunami, there are also 29 real-time tide gauges all over the country. Through the hazards and risk-assessment software code REDAS, PHIVOLCS can evaluate potential earthquake hazards, create tsunami simulations, and predicting the number of affected people. “The total population exposed to tsunami would be close to 14 million,” said Solidum. “But they will not be affected at the same time. It would depend on where the tsunami would occur. In NCR, for example, the prone population would be around 2.4 million. And the next highest would be 1.6 million in Region VII, 1.2 million in Region VI— and in Region IXA, around 1 million.”

Meanwhile, HazardHunter Philippines, which is open for public use, can assess hazards depending on the user’s specific location. “HazardHunter can also give you a more detailed tsunami hazards assessment because it can provide you a map showing the different areas that will be affected by different tsunami heights. It is color coded, indicating areas prone to various tsunami heights.” Solidum appealed to the public to take advantage of the “Report a Disaster” website. Here, people can post pictures and videos of current risks and hazards in their areas, and describe disasters impacts, which can help the government’s risk and impact assessments.

Screencap of “Report a Disaster” website

Screencap of “Report a Disaster” website

“In the Philippines, we use a simple tsunami information or warning scheme,” explained Solidum. “We will evacuate once the tsunami information is categorized as a tsunami warning. We expect a destructive tsunami of more than 1 meter and this would need immediate evacuation of coastal areas. Boats at sea are advised to say offshore — in deep waters.”

Shake, drop and roar

Because local tsunami can be very fast, people need to know its natural signs:

Shake – refers to a strong earthquake.

Drop – refers to the sea level receding fast.

Roar – refers to the unusual sound of the returning wave, which indicates a tsunami.

After an earthquake, Solidum recommends for people near the shore to immediately move to elevated ground inland, or take refuge in tall and strong buildings. “If they have not moved at all, once they hear the tsunami and there are unusual sounds, there might not be enough time. They really need to respond immediately,” warned Solidum.

PHIVOLCS also released tsunami safety and preparedness measures on their website:

- Do not stay in low-lying coastal areas after a felt earthquake. Move to higher grounds immediately.

2. If unusual sea conditions like rapid lowering of sea level are observed, immediately move toward high grounds.

3. Never go down the beach to watch for a tsunami. When you see the wave, you are too close to escape it.

4. During the retreat of sea level, interesting sights are often revealed. Fishes may be stranded on dry land thereby attracting people to collect them. Also sandbars and coral flats may be exposed. These scenes tempt people to flock to the shoreline thereby increasing the number of people at risk.

Solidum stressed the importance of community-based preparedness, built on planning and drills to create the following output:

- development of evacuation plans based on the hazard maps

- installation of different types of signage (signage for hazards, signage for the evacuation area, signage for the directions to go to the evacuation area)

- conducting of seminars and lectures

- drills

Tsunami preparedness during COVID-19

The devastation of several typhoons this year, coupled with the country’s location in the Pacific Ring of Fire, are proof that the Philippines is prone to various hazards. Because of the

COVID-19 pandemic, Solidum admitted that PHIVOLCS had to rethink their training methods. “Before, we actually go down to various coastal communities and conduct lectures in the evening, so that people who worked in the daytime can also attend. But the pandemic has enabled more people to listen because of the social media platform and our webinars. We’ve reached more people in terms of information campaign. But we hope that local government disaster managers will do the actual preparedness at the community level.”

Solidum noted that though COVID-19 continues to cause loss of lives and the disruption of public services, mobility and economic development, tsunami can create far more devastating impacts. “We will see the physical impacts through buildings, infrastructures, property, water supply pipes, electrical supply, communication system, roads, bridges, and ports. This is in addition to the physical impact on people because of the collapsing houses or the impact of the large volume of water. We have science, technology, and innovation from DOST that can help in preparedness and disaster risk reduction. We need to use it, but we need to share this information to the communities and the public,” he ended.

Watch the full press conference from PHIVOLCS.

Watch Panahon TV’s primer on tsunami.

Agay Llanera

An hour before midnight on October 26, 1978, Super Typhoon Kading was at its peak in the country, bringing torrential rains that caused the water level at Angat Dam to swell. Because stored water, when reaching a critical high level, might cause dam structures to break, the National Power Corporation (NPC) opened all its three floodgates to 8 meters. As the rains continued to pound, adding to the dam’s water level, NPC decided to further open the floodgates to its maximum height of 14 meters by 6 a.m. the next day.

This result was a catastrophe. With the sudden dam release, several towns in Bulacan near Angat Dam was instantly flooded. But the damage in houses, farms and working animals amounting to millions of pesos was not the only tragedy; with the dam’s spillways being opened without prior warning while residents were asleep, almost 200 people died in the sudden floods.

Civil suits were filed against NPC. Complainants all attested that they had not been warned of the maximum water release. Lives could have been saved if the dam release operation was done earlier and more gradually, and if there were proper communication among the sectors involved. In 1993, the suit was won, and NPC settled by giving 5 million pesos to families of those who had died.

But the tragedy was a wake-up a call to the government, which recognized the protocol gaps in dam release. In 1983, it began the Flood Forecasting and Warning System for Dam Operation. Implementation began in 1990, while the system became fully operational in 1992. The project led to the establishment of the PAGASA Data Information Center, flood forecasting and warning systems in both PAGASA and dam offices, hydrological stations, warning posts, and repeater and monitoring stations.

MARIS Dam in Nueva Ecija releases water (photo courtesy of NIA-Magat River Integrated Irrigation System)

Giving a dam(n)

PAGASA aims to manage the flooding risk caused by dams with its daily-updated products and services:

- Basin Daily Hydrological Forecast

- Flood bulletins

- General Flood Advisories (GFA) – Regional

- Status of Monitored Dams

Rosalie Pagulayan, a hydrologist at PAGASA, emphasizes the importance of risk management in harnessing the full potential of our dams. “Major dams are multipurpose,” she says. “They generate power, irrigate farms, provide potable water and controls flooding. During the rainy season, the dam stores excess water, keeping it from inundating the rivers and communities.” Angat Dam, in particular, provides 97% of Metro Manila’s water requirements, and irrigates 31,000 hectares of farmlands in Pampanga and Bulacan.

Though dams are meant to prevent flooding, extreme weather events that bring massive rains can force dam operators to conduct water releases.

But even the frequency of tropical cyclones in our country is a double-edged sword. “Many complain about the inconvenience of the rainy season, but upon studying our climate, a former PAGASA director was able to determine that 50% of our rain comes from tropical cyclones. If we don’t have tropical cyclones, our water supply suffers. Other weather systems are also important; the northwest and southwest monsoons bring 38% of our rain, while the ICTZ [intertropical convergence zone] brings 12%.” She adds that rains are important in crop irrigation and pushing out atmospheric pollution.

Pagulayan, who has been working in PAGASA for 15 years, says that there are protocols before spillways are opened. “Even before a typhoon comes, we predict how much rainfall it will bring. We give the data to the different dam offices, which compute the expected increase in water levels. To accommodate the incoming rain, the dams conduct pre-release—but only according to the river’s capacity to prevent flooding.” She adds that aside from measuring the amount of rain in the watershed, PAGASA also measure the rain’s impact. “There’s a warning post from dam offices before they release water. There’s ample lead time, so for example, if they’re opening the gates at 4 p.m., they warn residents as early as 10 a.m. so they can prepare.”

How flooding risks can be better managed

In other parts of the world, river systems span countries, such as the Brahmaputra River, which comes from India but flows downstream to Bangladesh. The famous Danube River also comes from several European regions. Such a situation calls for strong international coordination when the source of the river swells, and flows down to various countries and territories in low-lying areas.

But Pagulayan says this is not a problem in our country. “We are blessed with big river systems. We manage our own rivers, and solely benefit from them. Our rivers traverse through various municipalities, provinces and even regions.”

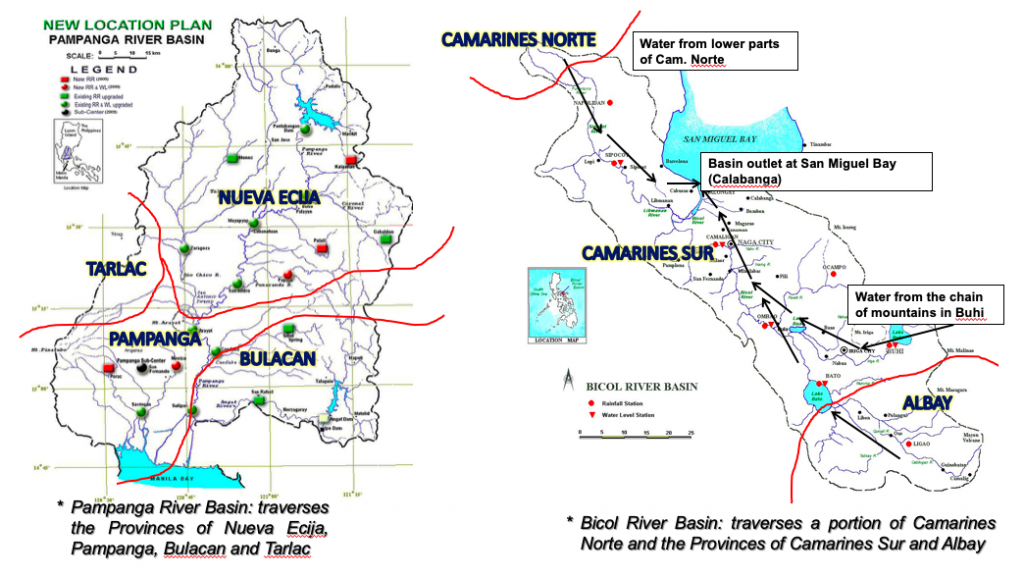

In the left graph above, Pagulayan shows how water from Nueva Ecija flows down to the Pampanga river basin, and contributes to a portion of Tarlac and Bulacan. “Our river systems encompass a lot of areas so disaster managers in these zones should be seamless in their communication and info-sharing.”

Meanwhile, as shown in the right graph above, water from the Bicol river basin comes from Albay, Camarines Norte, and mostly Camarines Sur. “But the Camarines Norte source is very important because rains are strong there, and because of its elevation, water flows down very fast,” shares Pagulayan. “All these rivers are owned by the Philippines. We don’t share them with other countries or regions. We are the only ones who can harness their potential.”

In areas that receive a lot of rain, dams and water reservoirs are built in mountainous areas, which can hold excess water. But watershed deforestation is an issue, leading to its decreased capacity for water storage. This may lead to flooding during the rainy season, and water supply shortage during the hot and dry season.

Risks also increase when people build their homes and livelihoods near waterways and flood plains. “They may find it convenient to set up livelihoods that require water, such as farms, in those areas, but once water is released, their safety is compromised,” explains Pagulayan. “Flooding also negates development efforts, and destroys agricultural products and infrastructure. But the worst risk of all is the loss of lives.”

MARIS Dam’s spillway in Nueva Ecija (photo courtesy of NIA-Magat River Integrated Irrigation System)

Moving forward

To foster good relations with dam offices and local government units (LGU), PAGASA regularly conducts information and education campaigns, public information drives, and communication drills. “For every disaster, the challenge, I think, is communication, so this is what we constantly develop. We can’t stop; it has to be continuous so we can improve,” Pagulayan shares.

By practicing and strengthening the information flow from PAGASA down to the regional and municipal levels, data accuracy is ensured, allowing LGUs to map out action plans to lessen flooding impacts. “We learn from every experience how to convey data and information. We are open to change and we adjust our activities, so we can improve both our services and community action,” ends Pagulayan.

Communities can also mitigate risks by knowing what to do before a tropical cyclone arrives and causes flooding.