My memories of the most impactful storm I have lived through are about as clear as they could be for a nine-year old at that time. In 2009, I saw Typhoon Ondoy catch the country by surprise and open the eyes of Filipinos to the importance of disaster risk reduction and management. Although my family was spared by the effects of the typhoon, it still hit close to home as the floods that Ondoy triggered submerged my grandmother’s home. As a young girl, the concept was inconceivable and surreal. I could not grasp how it was possible that the house I visited weekly could be buried under nearly ten feet of water. To this day, the events of Ondoy remain a core memory for me—despite having been minimally affected by it. Thus, I could only imagine how thousands of other Filipinos felt after the disastrous events last November.

November 2020 has been anything but kind toward the country. A handful of storms consecutively ravaged our nation, leaving many homeless, hungry, and helpless—all while still in the midst of a global pandemic.

Just recently, hundreds of Filipino families from the Cagayan Valley once again fled to evacuation centers as villages were flooded due the overflowing Cagayan River. This happened merely a few weeks after the province was devastated by the greatest flooding it has experienced in the past forty years.

Last November 12, Typhoon Ulysses submerged Tuguegarao City. Houses were literally underwater, people were screaming for rescue from their rooftops, and in lieu of cars, rubber rescue boats roamed the streets. Media footage from the province depicted scenes that seemed surreal — as if they were taken straight out of a sci-fi or apocalyptic film.

Footage of helicopter dropping relief goods in Cagayan (Video courtesy of Philippine Air Force)

The catastrophe resulted in 29 lives lost from flooding and landslides in Cagayan Valley. Damage brought by Typhoon Ulysses was compounded when the seven spillway gates of Magat Dam in Ramon were opened. This was due to the dam reaching its capacity limit, causing water to overflow into the towns, resulting to the wreckage that Cagayanos are still trying to recover from weeks after. Until now, people are asking: Who should be held liable for the drowning of Cagayan?

The Men behind the Curtain: Magat Dam Operators and Engineers

The volume of approximately 106 Olympic-sized swimming pools was the amount of water released when Magat Dam opened its seven spillway gates. The NIA-Magat River Integrated Irrigation System (Mariis) said this was a necessary decision to prevent the breaking of the dam—which would have resulted to an even greater disaster.

According to Mark Timbal, spokesperson of the Office of Civil Defense, the dam reaching its full capacity was due to the overflowing of the Cagayan River — caused by the multiple, consecutive monsoons and storms that hit the country. However, fingers were being pointed toward the dam operators because of the lack of proper notice to Cagayan Valley citizens before the dam release. Furthermore, Magat Dam’s operators were under fire for only opening the gates at the height of Typhoon Ulysses’s impact and not earlier—given that the swelling of Cagayan River was already occurring before the typhoon had made landfall.

NIA-Mariis claimed that advisories regarding the dam’s activity were duly made, utilizing various channels in doing so. Advisories about the opening of two of the dam’s gates were released as early as November 9—a week before Typhoon Ulysses struck. Nonetheless, Cagayan Governor Manuel Mamba acknowledged that the announcement came on short notice.

The Men behind the Country: President Duterte and His Administration

In the midst of Typhoon Ulysses’s terror, Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque pleaded netizens to stop fueling the trending hashtag #NasaanAngPangulo. This hashtag first gained popularity in early November when Filipinos were wondering why the president was not visible while the nation braced for Typhoon Rolly, which had already been identified as the world’s strongest storm this year. The hashtag once again resurfaced when the President was nowhere to be found at the peak of the typhoon’s devastation.

Last November 26, 2020, the Senate approved the national budget for 2021, in which 21 billion pesos will be allotted for the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (NDRRM) fund, while 15 billion pesos will be designated for the rehabilitation spending of Local Government Units (LGUs). The allocation seemed hardly enough to attend to the needs of severely stricken areas such as Cagayan, Isabela, Bicol, and Catanduanes — all affected by the four typhoons this November. The total amount of damage pegged for Typhoon Rolly amounted to Php 11 billion, while Typhoon Ulysses was estimated to have cost the country a total loss of nearly Php 13 billion.

The Men Behind the Climate Emergency: Capitalists and Corporations

The swelling of the Cagayan River was caused by the staggering amount of rainfall brought by the consecutive typhoons that affected the country prior to Ulysses. It is worth noting, however, that existing environmental damage worsened the effects of the opening of the spillways and the flooding. Due to the deforestation in the mountains of Cagayan Valley, yellow corn farming practices, and the use of toxic herbicide, natural resources meant to cushion the impacts of disasters were non-existent.

As early as 2018, there have already been reports regarding the illegal logging at Sierra Madre as investigated by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). For the past ten years, this prohibited trade has persisted. As the longest mountain range in the country, Sierra Madre is the country’s largest natural barrier against the approximately 20 tropical cyclones that enter the Philippines yearly.

Individuals may play a role in mitigating these environmental attacks and lessening the damage to the environment, but it would be unfair to pressure the masses for change when corporations are more capable of bringing widespread effects — if they change their environmentally exploitative practices. For years, I beat myself up — not to mention those around me — for using wasteful, plastic straws. It took me a while to realize that in spite of my individual efforts in being environmentally friendly, my endeavors are merely trivial. The phenomenon of eco-fascism continues to burden the working class with responsibility while leaving those in power unchecked. It leaves the masses with the burden to purchase more costly ecological products and the pressure to switch to a more “sustainable” lifestyle, while billionaires and corporations continue their consumerist practices that deplete and degrade natural resources—and still end up profiting from these.

With all this being said— what now? There’s a saying that says it is not a sin to be unaware; but it’s a sin you choose to look away despite having your eyes opened. The work, therefore, does not stop at finding accountability.

Continue to donate and help Cagayan.

In light of the recent disasters, we have seen Filipinos step up when the government failed to do so. Although this should not equate to absolving those in power of responsibility, there are ongoing donation drives in support of relief operations for Cagayan that are accepting cash and in-kind donations.

Stay informed.

It is vital to keep ourselves updated and informed about the policies and environmental decisions which impact all of us. Case in point: Sierra Madre continues to be in danger due to the construction of the Kaliwa Dam — said to be the solution to Metro Manila’s water issues. The construction of the dam will not only bring ecological destruction but also displace local communities located near the mountain range. As stakeholders, it is our responsibility to make our voices heard regarding decisions on matters like these — and it is through staying informed that we create more informed stances.

Engage others in conversation.

Ultimately, I wrote this article, hoping to broaden our perspective on the depth of these issues. In line with staying informed, engaging others in discourse about these topics generates a constant conversation that helps issues like this remain in the public sphere.

Finally, for the answer to the question: whodunnit? I’ll leave that for you to decide.

Sources:

Corcione, A. (2020, April 30). What to Know About Eco-Fascism – and How to Fight It.

Retrieved from https://www.teenvogue.com/story/what-is-ecofascism-explainer.

Deiparine, C. (2020, November 5). Total cost of damage from ‘Rolly’ now at P11 billion — NDRRMC. Retrieved from https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2020/11/05/2054788/total-cost-damage-rolly-now-p11-billion-ndrrmc.

Deiparine, C. (2020, November 22). ‘Ulysses’ cost of damage now at P12.9 billion. Retrived from https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2020/11/22/2058624/ulysses-cost-damage-now-p129-billion.

Gotinga, J. (2020, November 26). Senate passes P4.5-trillion 2021 budget bill on final reading.

Retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/nation/senate-passes-trillion-2021-national-budget-bill-third-reading-november-26-2020.

House to seek ₱5-B increase in calamity funds under 2021 budget. (2020, November 22).

Retrieved from https://www.cnn.ph/news/2020/11/22/House-Velasco-increase-calamity-fund-2021-budget.html.

Miraflor, M. B. (2020, November 17). Kaliwa Dam feared to worsen flooding in Metro Manila.

Retrieved from https://mb.com.ph/2020/11/17/kaliwa-dam-feared-to-worsen-flooding-in-metro-manila-1/.

Philippine Daily Inquirer. (2018, July 12). Logging continues in Sierra Madre – DENR. Retrieved

from https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1009508/logging-continues-in-sierra-madre-denr.

Ropero, G. (2020, November 15). Cagayan, Isabela residents warned of Magat Dam water

release: NIA. Retrieved from https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/11/15/20/cagayan-isabela-residents-warned-of-magat-dam-water-release-nia#:~:text=%22It%20is%20necessary%20to%20release,Valley)%2C%22%20it%20said.

Salaverria, L. (2020, November 14). Roque plea to netizens: Stop asking ‘Nasaan ang

Pangulo?’. Retrieved from https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1360495/roque-plea-to-netizens-stop-asking-nasaan-ang-pangulo.

Typhoon Donation Drives. (2020, November 23). Retrieved from https://theguidon.com/1112/main/2020/11/donation-drive-crowdsourcing/ .

Visaya, V. Jr. (2020, November 17). Deaths from ‘Ulysses’ floods in Cagayan Valley reach 29.

Retrieved from https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1122127#:~:text=Thirteen died in Cagayan province,from floods after the typhoon.

Visaya, V. Jr. (2020, November 18). Severe flooding shows Cagayan Valley environmental risks.

Retrieved from https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1361922/floods-show-cagayan-environmental-risks.

https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/147554/flooding-in-northern-luzon

https://twitter.com/inquirerdotnet/status/1327879577058775040?s=21

Last October 2, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) released a La Niña Advisory, announcing the onset of above-normal rainfall conditions in the country.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), La Niña is a “cold event” that pertains to “below-average sea surface temperatures across the east-central Equatorial Pacific.” Analiza Solis, chief of PAGASA’s Climate Impact Monitoring and Prediction Section stated that the weak habagat (southwest monsoon) experienced from June to September this year was indicative of an impending La Niña. “Historically, below-normal rainfall conditions in areas under the Type 1 Climate (western parts of Luzon, Mindoro, Negros and Palawan) during the habagat season is a precursor or part of the early impacts of La Niña.”

Though “weak and moderate La Niña” is expected to persist until March 2021, PAGASA Administrator Dr. Vicente Malano warned to never underestimate its possible effects. “In 2006, Guinsaugon in Leyte experienced a massive landslide. It caused considerable damage in properties and deaths.” The disaster was believed to be triggered by an earthquake in Southern Leyte, and two weeks of non-stop rains induced by weak La Niña. The landslide buried around 980 of the village’s population of 1,857.

What to expect

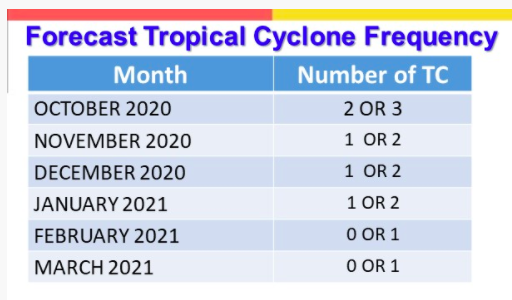

The approaching amihan (northeast monsoon) is expected to enhance La Niña. Solis explained that the rainfall forecast for October this year until the first quarter of 2021 is 81 to 120% more than the normal. Areas most likely to be affected are MIMAROPA (Mindoro, Marinduque, Romblon, and Palawan), Visayas and Mindanao. Because of the 2006 landslide, PAGASA is also closely monitoring western Luzon, even if it is normally dry during La Niña. “Day-to-day forecasts are crucial, supported by tropical cyclone warnings and sub-seasonal forecasts, so we can prepare for possible extreme weather and rainfall events,” Solis said, adding that this La Niña, five to eight cyclones are expected until March 2021.

(source: PAGASA)

(source: PAGASA)

Preparing for Possible Outcomes

According to Dr. Renato U. Solidum, Jr., the undersecretary for Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate, various agencies should focus on Disaster Risk Reduction Management (DRRM). “First, we need to monitor the different weather and climate phenomena, which PAGASA is doing. Second is assessing hazards and risks, which involves identifying the risks, their effects and the affected areas. Third is disseminating information and warnings to different sectors through proper communication channels. And fourth—the most important of all—is to have an effective and efficient response.” This includes mitigation measures, their effectivity, and a quick response that will lead to quick recovery.

Impact on Agriculture

Solis stated that during La Niña, low-lying agricultural lands are prone to floods, which may produce extensive crop damage. Recurring rains also increase the possibility of pests and crop disease, and may lead to river flooding and dam spillage.

Impact on Health

During excessive rainfall, there is a prevalence of waterborne diseases such as cholera and leptospirosis in flooded areas—things we need to avoid, along with loss of lives from flashfloods.

Impact on Environment

Landslides and mudslides are possible, while coastal communities are warned against coastal erosions due to strong waves. In the urban setting, damage to infrastructures is possible, as well as urban flooding, economic losses, and increased traffic.

Angat Dam located in Bulacan (file photo)

Angat Dam located in Bulacan (file photo)

Filling our Dams

The water level in Angat Dam, which supplies 97% of Metro Manila’s water needs, has been slowly but continuously decreasing. “These past weeks, we’ve seen a decline in Angat, Pantabangan and other dams. Even if it rains in these areas, they don’t hit our reservoirs,” Dr. Malano reported. But because of the rainfall forecast during La Niña , our dams are expected to recover. Weather Services Chief Roy Badilla of PAGASA’s Hydrometeorology Division stressed this benefit of La Niña: “50% of our rainfall come from tropical cyclones and La Niña, so without the La Niña, our dams won’t have enough water.”

Solis encouraged the public to maximize rain water harvesting and storage to cope with the dry season from April to June. Flood warnings and advisories from PAGASA should also be monitored. To avoid floods, the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) is requested to remove road obstructions. As local government units and disaster risk reduction offices prepare for imminent disasters, farmers need to strengthen their post-harvest facilities to ensure the proper drying and storage of their produce. “Adverse impacts are likely over the vulnerable areas and sectors of the country,” Solis added. “While our dams have their fill of rain, we should mitigate the possible impacts of La Niña and the amihan.”

La Niña and the Pandemic

Though La Niña is a natural climate variability, Solis said that climate change might also be affecting its pattern. “Before the year 2000, strong El Niño and La Niña episodes occur at least every 7 to 10 years. But during the past decades, the intervals have been cut down to 5 to 7 years. Along with their increased frequency is the increased intensity of their impacts.”

Because this year’s La Niña is coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic, PAGASA’s OIC-Deputy Administrator for Research and Development Esperanza Cayanan emphasized the need for preparedness in evacuation centers. “We need to enforce physical distancing among evacuees, and make sure that these centers are not used for COVID-19 patients.” Solis mentioned the same concern for hospitals. “Health care centers and hospitals should prepare for additional patients with water-borne diseases, and to separate them from COVID-19 patients.”

In the meantime, Dr. Malano suggested the use of schools and churches, now empty because of the prohibition of mass gatherings and face-to-face classes. “Disaster risk reduction should be everyone’s responsibility. We need to cooperate with each other so we can open up these facilities for evacuees, allowing them to observe physical distancing.”

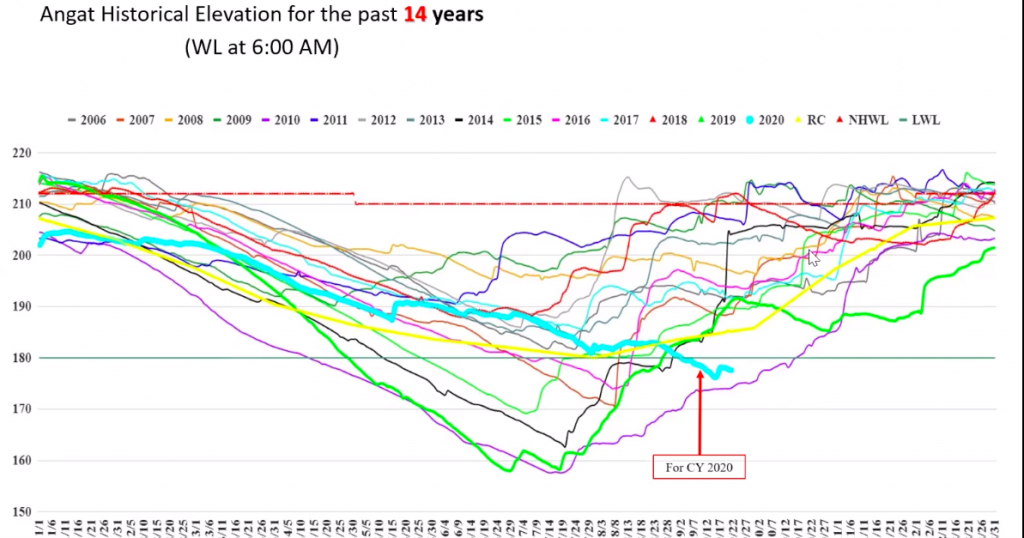

For the past weeks, the water level in Angat Dam, which supplies 97% of Metro Manila’s water needs, has been slowly but continuously decreasing. According to the Climate Outlook Forum of the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) last September 23, the dam’s level was at 177.3 meters, 32.67 meters less than its normal water level of 210 meters.

But according to Rosalie Pagulayan of the Hydro-Meteorological Division of PAGASA, historical data in the past 14 years shows that Angat Dam’s water level typically dips during this time.

Angat Dam’s current downward trend in light blue (graph from PAGASA)

Angat Dam’s current downward trend in light blue (graph from PAGASA)

“Its level continues to decrease, but we expect it to increase during the Northeast Monsoon. Even with no typhoons, we can expect Angat Dam to recover in the last quarter of the year,” says Pagulayan. This is based on the forecast rainfall of PAGASA’s Climatology and Agrometeorology Division, which shows an expected 386 millimeters in October, 294 millimeters in November and 129.5 millimeters in December.

Forecast Rainfall for the remainder of 2020

| October | 386 millimeters |

| November | 295 millimeters |

| December | 129.5 millimeters |

Metro Manila’s Main Water Source

The Angat Reservoir and Dam is located in the Angat Watershed Forest Reserve in Norzagaray, Bulacan. According to Manila Water, the dam supplies the water requirements of Metro Manila, and irrigates about 31,000 hectares of farmlands in Pampanga and Bulacan. It also generates hydroelectric power for the Luzon Grid, and holds water to reduce flooding in downstream towns and villages.

Top photo of Angat Dam taken last April 13, 2010 when water levels hit the critical 180 meters above sea level. Photo at the bottom with the structure completely exposed, was taken last July 16, 201, when levels reached a historical low of 157.55 meters. (Top photo by Joseph Agcaoili /Greenpeace. Bottom photo by Gigie Cruz-Sy /Greenpeace)

Top photo of Angat Dam taken last April 13, 2010 when water levels hit the critical 180 meters above sea level. Photo at the bottom with the structure completely exposed, was taken last July 16, 201, when levels reached a historical low of 157.55 meters. (Top photo by Joseph Agcaoili /Greenpeace. Bottom photo by Gigie Cruz-Sy /Greenpeace)

The dam usually stores enough water for Metro Manila’s 30-day supply. But El Niño, which refers to the unusual warming the oceans giving way to higher temperatures, can affect dam levels. On July 18, 2010, Angat Dam decreased to its all-time lowest level of 157.55 meters, the difference from its normal level roughly equivalent to the height of an 18-storey building. Because of El Niño, rain was below-normal, drying up the rivers that led to Angat Dam. Irrigation in Bulacan and Pampanga was cut to give way to the water needs of Metro Manila, which still experienced service interruptions. The government distributed relief goods among farmers and their families because they were unable to harvest.

Last year’s El Niño brought the Angat Dam down to 159.43 meters, just 2 meters more than its lowest record in 2010, prompting the National Water Resources Board to further reduce the allocation for Manila Water and Maynilad Water Services. Over 6 million residents of Metro Manila, Rizal and Cavite experienced daily rotational water interruptions from six hours to as much as 21 hours. Because of this, hospital operations and businesses were affected with some restaurants, carwashes and laundry shops closing temporarily.

Residents waiting by the roadside for fire engines to fill up their water containers in 2019

Residents waiting by the roadside for fire engines to fill up their water containers in 2019

Why We and our Dams are in Danger

According to the World Population Review, Manila is now the most densely-populated city in the world with over 42,000 residents per square meter. Data from the Philippine Statistical Authority shows that over 21.3 million people live Metro Manila.

Overpopulation created a spike in water demand, especially during the sweltering El Niño season of 2019, one of the reasons a Manila Water representative pointed out as the cause of reduced water levels in dams. But the water crisis is a global one, which the Union of Concerned Scientists in the U.S. also attributes to climate change. Global warming alters the water cycle, affecting the “amount, distribution, timing and quality of available water.” While a warmer climate speeds up the evaporation of water on land and in oceans, it also holds more water that can be released through devastating typhoons, causing massive floods.

The Philippines’ water crisis also extends to limited access to water and sanitation outside the metropolis. The World Health Organization states that out of the 105 million living in the Philippines, around 7 million depend on water sources that are unsafe and unsustainable. In fact, one of the country’s leading causes of death in 2016 was acute diarrhea, causing over 139,000 fatalities.

An unreliable water supply severely affects public health, pushing people to look for other drinking water sources that may be unsafe. Basic hygiene—a must during this pandemic—is also compromised as one needs to thoroughly wash themselves, their clothes and their food to prevent infections from COVID-19 and other illnesses. When water pressure in pipes are low because of scarce supply, elements can contaminate the water once the pressure is restored.

Before Manila Water implemented rotational service interruptions in October last year, Metro Manila residents went on panic mode and stored water ahead of time. The move lowered water pressure, limiting its flow and distribution toward high places. WHO also cautions against the improper storing of water as this can allow mosquitoes to breed, possibly increasing the risk of diseases such as dengue fever.

Solving the Water Crisis

While individuals are responsible for their own health and safety by making sure their drinking water is safe and free from contamination, WHO states that the government also needs to provide long-term solutions. Groundwater and surface water from rivers and lakes will not last long when exacerbated by climate change and a growing population.

“Strategies such as the application of improved rainwater collection systems and state-of the-art desalination technologies coupled with renewable energies can be used in the Philippines,” says Environmental health technical officer in WHO Philippines Engineer Bonifacio Magtibay on the WHO website. “By adopting innovative and long-term solutions, the Philippines can ensure water for all that will protect the peoples’ health and help drive sustainable development forward.”

Pagulayan also reiterates that though PAGASA expects Angat Dam to recover, residents must not be complacent. “We have always called for the responsible use of water. This is a very important commodity because we use it for almost all our activities. Even if we’re not experiencing El Niño or other weather systems, we should always be looking at how we can maximize our resources. Let’s not waste water.”

For more tips on conserving water, watch this.

For more details on the Angat Dam, watch Panahon TV’s report.