Toulouse, the capital of the Occitanie region in Southern France, is rich in history and culture. It was part of the Roman empire until the 5th century, and is now known for its aerospace industry, housing Europe’s largest aerospace center, including the French space agency.

It had a huge role in the history of Catholicism. It is where Romans persecuted early Christians and martyred a saint, and the site of a religious riot that started the French Wars of Religion. Toulouse became the templar stronghold in the first crusades, and Saint Dominic founded the Dominican Order here. Currently, it is home to several cathedrals, including the UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Basilica of St. Sernin, Europe’s largest surviving Romanesque building.

Toulouse is France’s fourth-largest city, whose center’s architecture is mainly composed of terracotta bricks, earning it the title, “The Pink City”. This is where we find Marjorie Mosura-Dumont, who has been residing here for 3 years.

Marjorie and Henri strolling in town before the nationwide lockdown during COVID-19

Marjorie and Henri strolling in town before the nationwide lockdown during COVID-19

After marrying Henri, my French fiancé, I moved to Paris in 2010. I loved Paris because of its beautiful architecture and buildings, but after a year, he said he was tired of its gloomy weather and gloomy people. We agreed to move to the Philippines slowly by backpacking from Paris to India, Nepal, and other countries between there and Manila.

After living in Metro Manila for five years, a lot of factors led us to decide to return to France. His nuclear family came from the north but decided to settle in the south of France, including his brother who was based in Toulouse, so we chose to live here.

Toulouse vs Paris

Toulouse is in the southwest of France, close to the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean Sea. This is perfect for us because we love hiking, and we once trekked all the way to Spain. It’s one of the stops in the Camino de Santiago or the Way of Saint James, which is a pilgrimage you do on foot for a month. We’re also conveniently close to another pilgrimage site called Lourdes.

Marjorie hiking to Lac d’Espingo in Pyrenees

Marjorie hiking to Lac d’Espingo in Pyrenees

The city has a distinct architecture and it looks magical a few hours before sunset. It’s well known for its terra-cotta bricks that glow pinkish-orange.

In terms of museums, Paris has the upper hand. Museums here are few, and mostly house roman and medieval pieces. The theater scene here is also limited, but it feels more intimate.

History is a huge part of Toulouse, which is the birthplace of Aeropostale. After World War I, the post service company delivered mail from Toulouse to different parts of the world, including Casablanca and South America. The flights were a big deal because before then, mail traveled only by boat. Because of Aeropostale, French colonies received mail much faster.

Aeropostale flights could be dangerous—something which Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the author of The Little Prince wrote about in his novel Vol de Nuit (Night Flight). Saint-Exupéry was an Aeropostale pilot, so The Little Prince was his semi-biography. Some streets here in Toulouse are named after him.

Through the years, Toulouse has retained its “aero center” status. Now, it’s famous for developing and building technology for the aerospace industry. One of the museums here is dedicated to outer space travel. The Airbus planes are also built here, which explains why there are a lot of engineers and expats in Toulouse. We also have a good amount of Irish pubs for some reason, with real Irish bands playing to boot!

Where the old Aeropostale airport used to be is now where you can find the La Halle De La Machine’s giant mechanical minotaur and spider. I shot a report for a news agency when they launched it a few years back. The minotaur and the spider walked all around old Toulouse for three days and it was a sight to see! Roads were closed, people ran after it, I saw a grown adult cry. I hung from a hotel window at the main square with photographers to take video of all that happening. It was other-worldly, but it was the magic of engineering, music and imagination.

A lot of people like it here because it’s warmer and less rainy than Paris, and the vibe is more chill. It’s France but a little Basque. The locals like drinking, partying, and going to tapas bars. We live a few minutes by foot from the Garonne River and the historic center, and we can walk to our favorite bar across the Pont Neuf bridge. Before the pandemic, we used to drink at the bridge and enjoy the music spilling from the bar. When our drinks ran out, we’d just duck back in for refills and rush right out into the fresh air. There seemed to be an unwritten agreement for the whole city to be out at five. I think that’s the best image I could draw for you about life here—seeing your friends, having a drink and watching the glow of the sun set on the pink city.

Toulouse and COVID-19

At the start of the quarantine in March, we had to print out a form indicating the date and time we left our home. For example, I’m going out on this date: March 11, from 1 to 2 p.m. We only had an hour to jog or walk the dog within a 1 kilometer radius from our address. Two household members at a time could go out of the house. For a time, the restaurants were closed, and the lines at the supermarkets were very long. Only ten people at a time could enter. But at least we were still allowed to walk and stretch outside, that helped manage my anxiety.

Back then we didn’t have a lot of cases in Toulouse, but there was still a shortage of face masks and they were very expensive. I made masks for a friend who is a nurse so she could distribute them at her hospital. She said other hotspots flew their patients here because our hospitals had a lot of empty beds. It was only last August when the government required face masks in the streets. Before that, we were only required to wear them in stores. In July, travel restrictions were lifted because the cases went down, and it’s too much to ask the French to stay at home during summer.

But things have changed after summer. We’re now one of the hotspots for COVID cases. We had a curfew for a few weeks and then the government decided to close the bars, restaurants and activity areas to prevent the spread of the disease. A lot of businesses closed down despite some monetary help from the government because they were still paying rent for shops that can’t open.

Despite the health crisis, what’s good about living in France is its universal healthcare. When I had a pulmonary embolism two years ago, the firemen came at 5 a.m. and took me to the hospital. I waited for my bill in the mail but nothing came! Henri and I try not to go to the doctor for every little thing to avoid overtaxing the system. Socialism is awesome only if everybody’s truly egalitarian. As a member of the middle class in the Philippines, it sucked to pay so much in taxes and get nothing in return when we needed money to treat my dad’s cancer.

Pinay in Toulouse

Toulouse is a rich melting pot. I have friends from many different countries that I would never have met if I didn’t go to my state-sponsored French classes. Thanks to them, I’ve learned a lot of fascinating things about life in South Africa, Syria, Turkey, Mexico, and the Ukraine (just to name very very few). On my end, I’ve introduced them to Pinoy food.

At first, it was hard to adjust to the fact that there were no Pinoy stores here, unlike Paris that has at least two. After early evening mass at St. Joseph’s Church near the Champs Elysees in Paris, there’s a Pinoy palengke at the church steps. In my first 4 months of living here, I didn’t hear anyone speaking Tagalog.

Then one time, I was at an Asian supermarket with my Vietnamese friend and I heard someone speaking in Cebuano. So I called out: “Ate, Pinoy kayo?” She said,“Oo!” It was comforting to know I had kababayans here. If you want ensaymada, pan de coco, or sapin-sapin I have connections. There may be no Pinoy store here, but there are enterprising Pinoys who make and sell native treats.

Here, I started painting again. My dad was a frustrated comic book artist, and one of the most precious gifts he gave me were art supplies. We used to bond over drawing things and he wanted me to be an artist, but I became a writer like my mom. When I got here, I started painting Filipino food just because I missed them. And I know I could have gotten a rambutan from a specialty store but I felt guilty and privileged about the contributing to the carbon footprint of one measly rambutan that isn’t really necessary for my survival. I just missed it, but I guess most of all I missed the context of it. So when I finished painting I threw in the baybayin script under the artwork to make it plain that I’m talking about this food as a Filipina, with the context it has as a thing you can see in the palengke or hanging in a tree, with the common experiences we have around it that nobody else might immediately understand, but give me a minute to tell you its story.

Marjorie’s adobo painting sticker with a background of a fortified city from the dark ages

Marjorie’s adobo painting sticker with a background of a fortified city from the dark ages

I’m part of a small painting community with five other Filipina friends. My friends have encouraged me to branch out into landscapes and flowers. I’ve tried that but I’ve mostly dug in my heels with Pinoy subjects. I started an Instagram account and (more recently) a website to share what I’m doing and reach out to people who are missing the same things I have. I’ve met some interesting people this way. I used to print my paintings on sticker paper and stuck them on random spaces around Europe. I thought about it as a way to teach my culture to anyone who would bother to look at what’s written under the painting of a tomato, for example. But if a Pinoy saw one, my hope is that they would realize that a fellow Pinoy passed through there, and that they’re not alone.

All in all, I like living here. Henri and I have always wanted to live in a place where we can grow things and here we get a lot of sun. For now we have an edible garden on our apartment balcony. So far, I’ve managed to grow calamansi, which I got from IKEA two years ago. Henri and I laughed about it then because they think it’s ornamental, but to me it was like the heavens opened. However, I think the age of innocence is at an end because Henri saw a fancy specialty store selling calamansi a month ago.

Marjorie’s calamansi harvest from her edible garden

Marjorie’s calamansi harvest from her edible garden

The thing is, we want to be self-sustaining. Eventually, we want to be able to recycle water and use renewable energy. We want to reduce our carbon footprint. But for now, Toulouse fits our purpose, and I’m soaking in its laid-back vibe, allowing it to fuel my Pinoy-inspired art, wherever it takes me.

Sometimes, it only takes a small step to spark a movement.

When 26-year-old Ana Patricia “Patreng” Non decided to start a community pantry near her home in Maginhawa Street, Quezon City, it was because she wanted to help. “My small business was affected because of the lockdown,” she explained in Filipino in a Panahon TV interview. “But even if I didn’t have any income, I could still eat three times a day. I thought of those whose livelihoods depended on being out on the streets. They needed support.”

Soon, news about Patreng’s Maginhawa Community Pantry, fashioned from a bamboo cart, spread like wildfire. People came in droves, dropping off food donations, and getting food. The initiative was so popular that even the German Ambassador to the Philippines Anke Reiffenstuel dropped by to donate goods. She tweeted that she was “deeply impressed by the solidary spirit of the Filipinos.”

Patreng and her bamboo cart of donated goods (photo from AP Non)

Patreng and her bamboo cart of donated goods (photo from AP Non)

Maginhawa Community Pantry’s Evolution

To accommodate the growing volume of crowd and donations, the pantry relocated to a bigger space at the Teacher’s Village East Barangay Hall. Quezon City authorities were called in to maintain health protocols. But the line continued to grow, extending all the way to Philcoa along Commonwealth Avenue. Senior citizens, though prohibited to go out of their homes, joined the queue. To get in line early, people broke curfew.

To address these challenges and to meet the needs of community pantries that mushroomed in the area and all over the country (as far as Mindanao), the Maginhawa Community Pantry recently announced that it would no longer serve beneficiaries. Instead, the pantry has evolved into a drop-off point for donations, which will be distributed among other pantries and places that needed aid. This decentralizing move seeks to promote better barangay coordination and observation of health protocols, and to spread out the crowd lining up for goods.

Inspired by Patreng’s initiative, UP Campus residents set up their own community pantry. (photo by Mary Jhoy Aap)

Inspired by Patreng’s initiative, UP Campus residents set up their own community pantry. (photo by Mary Jhoy Aap)

Ensuring Safety in Community Pantries

Though initiating community pantries is commendable, organizers should always remember that the country is still grappling with the pandemic. Safety and Preparedness Advocate Martin Aguda Jr. explained in Filipino, “Each time you go out—whether you’re an organizer, a volunteer, a donor or a beneficiary—you are at risk for COVID-19, especially in crowded community pantries.”

On the day when a senior citizen collapsed and died while waiting in line at a community pantry, the Quezon City government released its Community Pantry Guidelines to minimize health risks. Aguda also offers these tips:

Map out a risk management plan. Recognize the risks of your endeavor. How will these affect everyone involved? “You have to check the risks and you have to put in your safety measures,” stressed Aguda. The risk management plan involves wisely choosing the pantry’s location, which will largely depend on the crowd volume you are capable of handling. “Is this an area that will draw in crowds? You need to survey the place because from there, you can gauge your expected crowd.”

Check if your resources are enough. Make sure that the amount of goods you will be distributing matches the expected number of beneficiaries. “When the people outnumber the goods, that will result in long lines and extended waiting time. The longer people wait in line, the more they are exposed to other people and the risk of COVID,” shared Aguda. Limited resources may also cause people to forego discipline and cause a stampede.

Ensure the safety of everyone involved. Aside from making sure everyone is wearing a mask and a face shield, and is practicing physical distancing, organizers should also check the pantry’s surroundings. Aguda explains, “The location should be away from traffic to prevent accidents. Physical distancing can be enforced through physical markers. Enlist the help of safety officers or barangay officials to ensure that lines and health protocols are followed.” Aguda also suggested to set early operation hours so people don’t have to wait under the heat of the sun. This reduces the risk of heat stroke and dehydration.

Regularly brief the crowd. Reminding the crowd to follow health protocols cannot be made often enough. Because there’s always a fresh batch of people joining the line, always reiterate the measures to ensure their safety. Set an example by wearing PPEs and following physical distancing. Provide alcohol for public use.

“It all boils down to planning. We all want to help, but we don’t want to deal with unintended consequences,” warned Aguda. He advised people going to community pantries to also bring drinking water and umbrellas. “Learn to be practical. Remember your health is at risk.”

In turn, Aguda advised organizers to never let their guards down. “You need to protect yourself because you are interacting with different people. Don’t remove your mask at any time. Your volunteerism is a noble act, but you can still help others by ensuring your own safety,” he ended.

Watch Panahon TV’s full interview with Martin Aguda Jr. here.

For those who want to donate to the Maginhawa Community Pantry, visit its Facebook page.

This year’s Todos los Santos will be celebrated differently in light of the pandemic. From October 29 to November 5, cemeteries, columbaries and memorial parks are closed as a safety measure against COVID-19. But aside from visiting their dead outside these dates, Filipinos can still continue a semblance of tradition by lighting virtual candles for their loved ones through a website initiated by the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP).

A precursor to All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days is Halloween which, will now, be ideally spent at home. In Metro Manila, Western influences are strong with people holding costume parties, and trick-or-treating for kids in neighborhoods, malls, hotels and even in their parents’ offices.

A Brief History of Halloween

But what really is Halloween and how has it evolved into the colorful, festive celebration we know of today?

This tradition is rooted in the culture of Celts, who mostly lived in Ireland, the United Kingdom and northern France 2,000 years ago. Back then, the Celts donned costumes and lit bonfires to protect themselves from spirits. They believed that on the last day of October, the dead were free to roam the earth before they returned to their rightful place in the other dimension.

The Halloween we are currently familiar with is a mix of beliefs and customs of American Indians and ethnic groups from Europe. Halloween became especially popular during the latter part of the 19th century when millions of Irish immigrated to America.

Photo by Matej Novosad from Pexels

Photo by Matej Novosad from Pexels

Undas Culture

For us Filipinos, Halloween is merely party of a more solid tradition called Undas which, many speculate, is derived from the Spanish word honra meaning respect. From October 31 to November 2, we honor the dead in major ways.

Many travel to the provinces to visit the graves of their deceased. In cemeteries, visitors pitch tents even before October 31 to spend the night—or several nights. Memorial parks become venues for family reunions with potluck food. Some practice pag-aatang or offering food to the dead by placing it on their graves. Meanwhile, those at home light candles on doorsteps in the belief that these will guide lost souls toward the light of the after-life.

Pangangaluwa

If the West has its trick-or-treating, we have our own custom called pangangaluwa (souling). The original practice involves elders, who upon returning from the cemeteries on the evening of November 1, would wear white blankets to represent the spirits. When midnight struck, they would go from house to house, singing traditional songs and appealing for donations and prayers for the departed souls. Their eerie costumes and voices in the dark made for a hair-raising experience.

Sariaya in Quezon has revived pangangaluwa, a project initiated by the Sariaya Tourism Council (STC) in 2005 to raise funds for the town’s Belen Festival during Christmas. From October 27 to 30, young people dressed in ghoulish costumes visit neighborhoods. Like Christmas carolers, they serenade residents, who have been informed beforehand of the visit and solicitation of funds.

A scene from Biag ni Lam-an at the 2019 Semana ti Ar-Aria Festival (photo from the festival’s FB page)

A scene from Biag ni Lam-an at the 2019 Semana ti Ar-Aria Festival (photo from the festival’s FB page)

Semana ti Ar-aria Festival

In Ilocos Norte, the Semana ti Ar-Aria Festival is a weeklong celebration that attracts tourists from neighboring provinces and Manila. Ar-aria is Ilocano for ghost; but the festival does more than remembering the dead, it also involves art-related contests and activities. This is because events are tied up with the birth anniversary of political activist and renowned painter Juan Luna, who was born in Ilocos on October 23, 1857.

On its 9th year last 2019, Semana ti Ar-Aria highlighted Ilocano folklore, such as Biag ni Lam-ang (The Life of Lam-ang), an epic poem about an extraordinary warrior who is aided by magic during his quest for his father. The celebration’s highlights also included the Taray Ar-Aria (zombie run), trick-or-treating and street dancing.

San Antonio locals depict the Plaza Miranda Bombing in 1971, which killed 9 and wounded around 95 people, including senators. (photo by Jazel Kristin)

San Antonio locals depict the Plaza Miranda Bombing in 1971, which killed 9 and wounded around 95 people, including senators. (photo by Jazel Kristin)

Tumba-Tumba Competition

During Undas, San Antonio in Zambales becomes a macabre-looking neighborhood as residents dress up street corners to depict death scenes in time for the annual Tumba-Tumba Competition.

Tumba, Spanish for tomb, originally referred to shrines for the dead, peppered with flowers, candles, and images of saints. But with the Tumba-Tumba Competition, the tombs have evolved into homes converted into horror houses, sometimes complemented by dancing zombies and scary creatures perching on trees.

Jazel Kristin, who was once a judge of the competition gives us an idea of how grand the displays can get. “I’m always impressed by the effort that the community puts into them. They show the creative spirit of the Zambaleños in their depiction of everything, from horror movie characters to indigenous mythological creatures. They show familiar scenarios like capsized tourist boats, and political issues like the Ampatuan Massacre, Plaza Miranda Bombing, ISIS and the drug war.”

Locals re-enact the 1996 Ozone Disco Fire rendition before the tragedy. (photo by Geric Cruz)

Locals re-enact the 1996 Ozone Disco Fire rendition before the tragedy. (photo by Geric Cruz)

Jazel’s criteria for judging includes originality, creativity and effectiveness of storytelling driven by production design, involving sound, music, make up, costumes and props. “It’s a long night with people going in and out of the tumbas. So the actors always have to be in character to make their world believable.” For Jazel, the most memorable tumba she has seen is the recreation of the Ozone Disco Tragedy, acknowledged as Philippine history’s worst fire, which killed at least 162 people in 1996. “There was this house playing some music, a mirror ball hanging on the ceiling and under it were teenagers dancing, all covered in colorful strobe lights. When we returned the next day of judging, we saw all of them lying on the floor—a recreation of the Ozone tragedy. Simple execution but effective storytelling.”

Locals re-enacting Ozone Disco after fire (photo by Geric Cruz)

Locals re-enacting Ozone Disco after fire (photo by Geric Cruz)

Jazel considers the Tumba-Tumba competition as a creative way to bring the community together. “It gives people something to look forward to. It also gives us a peek into how certain events affected themm and how they use this tradition to shed light on tragedies and disasters, reminding people that yes, they did happen.”

With COVID-19 still rampaging across the globe, death has become a daily update in the news. But with these local customs, we see an underlying endeavor to better understand death, to see its many faces, and perhaps, come to terms with its true nature—about how death really is not the opposite of life, but an inevitable part of it.

In the Caribbean Sea, we find Jamaica, an island country popular among tourists. When the Spanish occupied it in the 16th century, they brought African slaves, which explains why majority of present-day Jamaicans are of African descent. Despite its small size, Jamaica’s global influence is considerable, birthing the Rastafari religion and reggae music—a music style that combines Jamaican folk music and American jazz, and rhythm and blues. The country’s capital is Kingston, which, like the Philippines, has a tropical climate and experiences frequent hurricanes (or in our case, typhoons) and earthquakes. In Kingston, we find Frances Alcaraz, a Filipino illustrator of over 25 books for children and adults published in various countries.

Frances (right) with daughter Rita and husband Stephen off to a Jamaican beach

Frances (right) with daughter Rita and husband Stephen off to a Jamaican beach

Journey to Jamaica

Even before I met my husband Stephen, a Canadian diplomat, I’d already enjoyed traveling. But since we got married in 2012, I’ve gotten the chance to not only tour exotic places, but also live in them.

In our first three years as a married couple, we resided in Sudan in North-East Africa. Three years later, we packed our bags and lived in Athens in Greece, where I gave birth to our daughter Rita. In 2018, we flew to Jamaica to live in Kingston.

The first time my husband and I got here, we exchanged looks, thinking the same thing: Jamaica and the Philippines are nearly interchangeable. It’s a tropical country with lots of beaches. People walk around in casual clothes and flip-flops. The Jamaicans are big on Christianity, so they devote their Sundays to church and family. Even the mangoes remind me of home, their taste and appearance similar to ours. The only difference is that Jamaicans don’t eat green mangoes. The first time I mentioned it to them, they found it weird. Because Jamaica is close to the U.S. and Canada, locals often go abroad to work—just like overseas Filipinos.

White-sand beach in Lime Cay off Port Royal, Jamaica

White-sand beach in Lime Cay off Port Royal, Jamaica

Living the Island Life

Because it’s a tourist destination, living in Jamaica is expensive, unlike in Manila. But similar to Manila, traffic can get really bad. Driving Rita to school usually takes 30 minutes, but with the killer combo of rain and rush hour, it could take us as long as two hours to get there.

But because it’s a small country, all the beaches and mountains are a driving distance from Kingston—about 3 hours at the most. You don’t need to take a plane or a boat to visit the more remote areas. The malls here are not huge, because people would rather visit the beach. The good thing here is that though Kingston is a concrete jungle, outside of it are pockets of paradise. The government makes it a point to not over-develop the tourist spots so they retain their natural charm.

You know when you watch movies with Jamaican characters who always say Ya mon? Well, it’s really the Jamaicans’ go-to expression! Everyone here says it, no matter their social status. It’s their equivalent of “okay” or “no problem”. From this alone, you can tell the Jamaicans are pretty chill. They have no boundaries. When you knock on their door, they welcome you right away. But what I had to adjust to is their directness. In general, we Pinoys don’t like to offend others, but Jamaicans like to speak their minds. At first, I found this behavior aggressive, but I’ve learned to be just as frank.

Colorful street art in Kingston

Colorful street art in Kingston

If you’re a foreigner in the Philippines, you can get by without having to learn the language because almost everyone speaks English. It’s the same way here. The first time I heard the local language Patois, I thought it was just heavily-accented English. But it’s a unique language on its own.

Despite their openness to foreigners, Jamaicans have strong national pride. They’re proud of their culture. You can see the Jamaican flag and its colors everywhere—on their beaches and even on their beach towels!

COVID-19 and Jamaica

During the first wave of the pandemic, we would get around 55 fresh cases a day. Then we closed our borders, and for some weeks, there were zero cases. A few months ago, we re-opened borders, and the cases began to climb again. The virus usually enters through Jamaicans returning from other countries. Because they’re very sociable like Pinoys, they meet up with relatives and hold big parties. So the government is much stricter now. Face masks are required, and there’s a curfew again.

Port Royal was the famous headquarters of pirates back in the 17th century.

Port Royal was the famous headquarters of pirates back in the 17th century.

Balancing Art and Motherhood

Aside from being a freelance illustrator, I used to teach Writing and Illustrating for Children at the Ateneo de Manila University. Ideally, I can do my illustrating gigs from anywhere in the world. But Rita is only 4 years old, and for now, she takes priority. Even if Jamaicans often hire nannies, I’ve decided not to. Sometimes I get so exhausted that I’m tempted to hire a nanny. But since I can afford put aside my career, I’m Rita’s primary caregiver.

This year, Rita was supposed to spend half-days in school, leaving me to fix my art portfolio. But then the pandemic hit and she’s home all the time. It’s hard when she has no one play with. When she complains about being bored, I craft toys for her.

In 2016, I finished my passion project— illustrating and self-publishing a coloring book with fairy-tale characters. I began a second one, but it was put on hold because I had Rita. The last children’s book I illustrated was in 2017. Now I’m taking illustrating courses to refresh my skills.

“Sirena” from Frances’s exhibit on Philippine mythical creatures

“Sirena” from Frances’s exhibit on Philippine mythical creatures

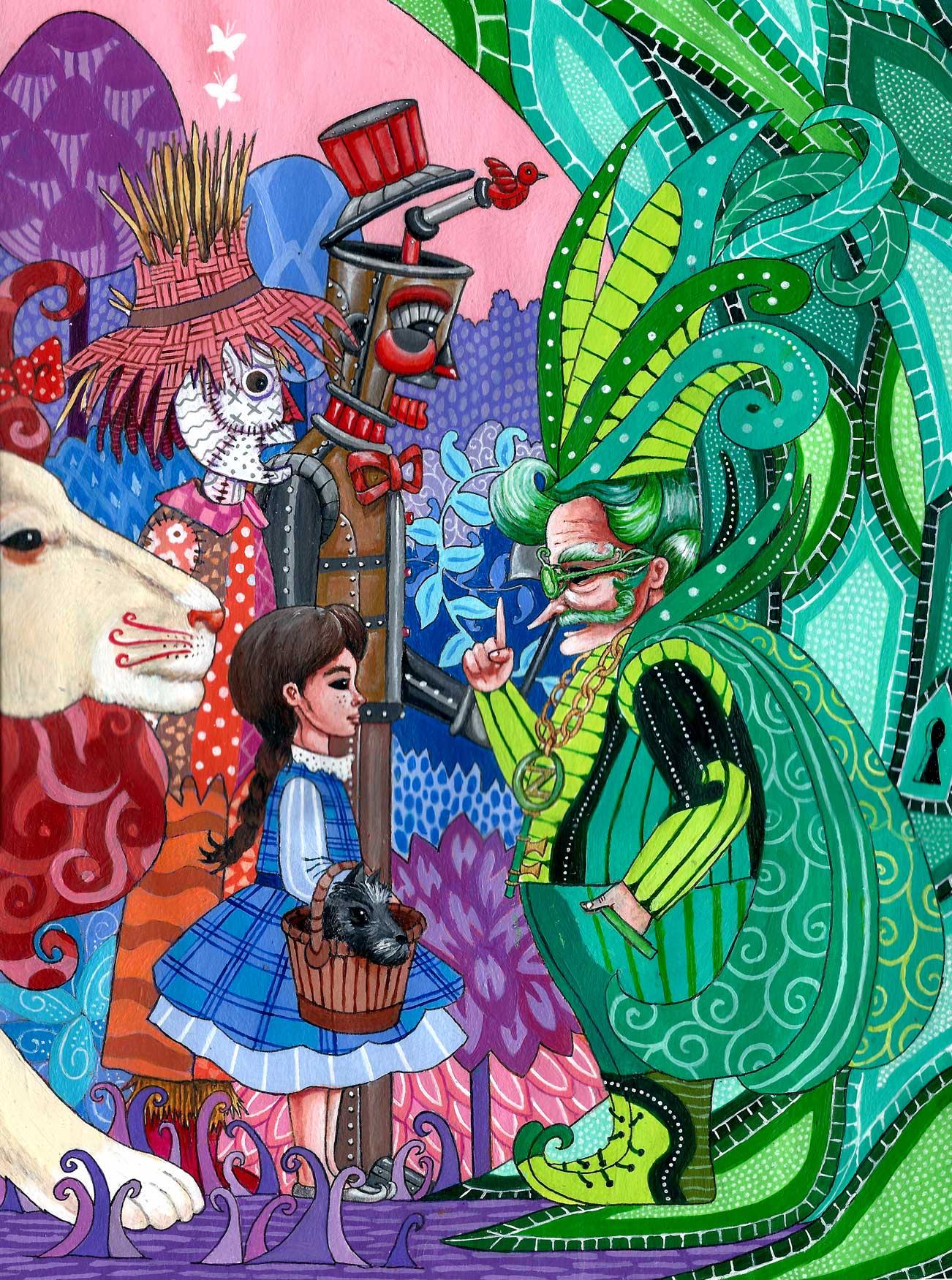

Wizard of Oz characters in Frances’s coloring book on fairy tales

Wizard of Oz characters in Frances’s coloring book on fairy tales

In every country I live in, I make it a goal to hold an exhibit. In both Greece and Canada, I partnered with the Philippine Embassy to showcase my paintings of Philippine mythical creatures. This year, I was hoping to do a visual retelling of Florante and Laura, but because of the pandemic, I’d have to postpone it. I’m not really a big fan of painting, but I do it so my skills won’t get rusty.

Eventually, my dream is to illustrate for big publishing companies in New York and Canada. But in the meantime, I’m trying to get back into the groove of my art.

Frances and Stephen by the pyramids in Meroë, Sudan

Frances and Stephen by the pyramids in Meroë, Sudan

Frances exploring the alleys of Mykonos, Greece

Frances exploring the alleys of Mykonos, Greece

Living out of a Suitcase

Because of Stephen’s work, I’ve learned to adjust wherever I am. There’s no perfect place. Sometimes, I fall in love with a place; sometimes I don’t—and that’s totally fine. I’ve learned to manage expectations. In Sudan, I learned to cook. In Greece, I learned to be a mother. And now that I’m in Jamaica, I continue learning skills and more things about myself. Every now and then, we take breaks and travel to learn more about the country we temporarily call home.

It’s a hard life and I love it. It’s not for everyone; some people hate packing up and moving every 3 years. But I enjoy traveling and I get bored staying in one country for too long.

Don’t get me wrong—I do miss the Philippines. I miss my family, my friends, and even my hairdresser. I’m looking forward to going back, but I’m also excited to discover new countries and cultures with my family. I want to see more of Asia. I’d like to live in Australia. I’d like to explore even more of Jamaica before we once again pack our bags, leave, and start all over in a new country.

Click here to learn more about Frances Alcaraz’s work as an artist.

In terms of area, Alaska is the largest state of the United States of America. Located in the country’s extreme northwest, Alaska’s capital city is Juneau, known for its rich wildlife. Hundreds of bird species, and black and grizzly bears occupy its forests; while its waters are home to humpback whales and orcas, as well as wild trout, halibut and salmon, making Juneau a famous fishing destination. In summer time, between May and September, thousands of cruise-ship passengers make a stop in this picturesque city. Here, we find Chris Mariano, who’s been living in Juneau for three years. She shares with us stories about her new home.

Chris Mariano, a Juneau resident since 2017

Chris Mariano, a Juneau resident since 2017

The first thing I noticed when the plane touched down at the Juneau International Airport was how bright it was. It was already 9:30 p.m., but the sun was still in the sky, blurred and subdued right as it was about to set. It was the last day of May in 2017, and the first day of the rest of my life. At that moment, it hit me that I was in a radically different country.

Right outside the boarding gates, the huge glass window showed the parking lot with a breathtaking background of towering snow-tinged mountains. The view was pretty as a postcard, except that it was big and real. I had to pause and breathe, Wow.

My family had been living in Juneau for 15 years, and they’d told me what life in Juneau was like. I thought I knew what to expect, but it turned out that everything was still going to be a big adjustment for me. Still, after more than a decade, I had my family with me—and with them, I felt that I could face anything.

Auke Lake

Auke Lake

Left behind

If I had been a minor at the time my family’s immigration application was approved, I could’ve gone with them to the U.S. But by then, I was already 26, and no longer considered a dependent. They called this “aging out,” when the children turned 21 before their green cards were processed. My parents and three sisters flew to Alaska to make their home there. I had to wait before a separate petition could be filed for me. It would take years.

At first, being left behind wasn’t too hard for me because I lived in a compound with relatives, so I still enjoyed a sense of family. I worked in advertising, which was both exciting and hectic, and I felt like I was moving up in the world. But when the holidays came, my relatives would go to their in-laws, and I’d make my own plans. I spent one Christmas with friends, volunteering for the Make-a-Wish Foundation. After we had spent the day with a young girl and her family at a theme park , my friends had to go to a family reunion. Although they invited me—maybe out of politeness, maybe pity—I went home alone.

But as I got older, I realized that I couldn’t be a part of my family’s milestones. One of my sisters got married and I wasn’t able to attend her wedding. Another sister graduated high school, then college. Eventually, I would have two nieces and a nephew that I would only see once in a while. I saw my family growing older in 2D through my computer screen. That was when it began to hit me that none of us were getting any younger, and I was missing out on so many things.

In the blink of an eye, 15 years had already passed. So when my petition was finally approved, I was ready to go and join my family.

Juneau sunset

Juneau sunset

Delightful Juneau

My trip to Alaska to live there was my first time in the States. My first impression of Alaska was really good. I spent my first few weeks going around Juneau and visiting other places in Southeast Alaska. Everyone told me that I was lucky that we were having a good summer then. But since I was still adjusting to the weather, I wore jackets throughout the season.

Juneau is the state capital and has about 36,000 people, but it’s still rural in a lot of ways. We only have strip malls and the roads are narrow. It’s halfway between a small town and a city, and it’s a great place to ease myself into living in a different country. The people are nice, and there’s a huge Filipino community here. There’s a bust of Jose Rizal sitting in a small spot downtown called Manila Square. When I walk the street, I see a lot of Filipinos, and on the bus, some strangers would offer me a seat because I’m Filipino. I would chat with them and discover what a small place Juneau really is, like how this woman I’m talking to turns out to be the aunt of my friend’s husband and so on. Simple things like that have made Juneau a nice place for me to live in.

Mountain trail during the summer

Mountain trail during the summer

Frozen bridge during the winter

Frozen bridge during the winter

Adjusting to Alaska

The biggest adjustment I had to make was getting used to northern summers. I know that the extreme north have it worse with their 24 hours of sunlight, but as someone from the Philippines, it bothers me that it never gets completely dark here at night during the summer. When I see sunlight, I automatically think that I have to be active and productive.

One time, I was finishing up my day at 2 a.m. and each time I looked out the window, it would already be light out. They call this civil twilight, that period before sunrise and after sunset when it would still be light outside. Even though the light isn’t particularly bright, I still couldn’t sleep. I’ve always been sensitive to light. I have to use thick curtains and eye masks to be able to sleep.

Walking across the frozen Mendenhall Lake

Walking across the frozen Mendenhall Lake

I like the winter better, when the opposite happens—the nights are long and the days are short. There were times that I’d wake up at 8:30 a.m., and it would still feel like dawn, or when I’d end my workdays at 4 p.m. when it would be completely dark.

In terms of weather, June is supposed to be the driest month so that’s the time we go out and travel. It’s very pleasant, and never gets too hot. But for the most part of the year, Alaska has rainy weather—much more rain than I’ve ever had in the Philippines.

Orca sighting

Orca sighting

Wild beauty

When it’s sunny, Juneau is really beautiful. Sometimes, when I’m riding the bus, I look out the window and just appreciate the place. It’s found in the Tongass National Forest, which is the largest U.S. national forest, and the largest remaining temperate rainforest in the world.

At the end of our street, there’s a gorgeous mountain, which I can see it from my bedroom window. Our home is about 35 minutes from the Mendenhall Glacier on foot, so during pre-pandemic summers, I would take a walk there almost every afternoon. During my work breaks, I would often invite a work colleague to walk around the downtown area. One of my favorite places is a cemetery just a few blocks from our office. It’s built on a hill and is the resting spot for the founders of Juneau. When I have time a little more time during my lunch break, a friend and I can even manage a short hike. On hikes, it’s common etiquette to greet and make eye contact with the people you meet on the trail. It’s a great safety measure too, since they may be the last people you see before you meet an accident or get lost. After the hike, I would return to the office, feeling energized and ready to tackle work.

Black and brown bears are known to make an occasional appearance in Juneau. That’s why everyone is mandated to lock up their food and garbage. Bears that are attracted to your neighborhood because of improperly disposed garbage can become ongoing threats and nuisances, and threats like them would have to be put down. Many Alaskans are used to bears. If one wandered into your neighborhood, you would know better than to approach it; if you saw one on a trail, you would keep your distance and make as much as noise as possible to drive it away.

Northern lights (photo by CJ Mariano)

Northern lights (photo by CJ Mariano)

Alaska is famous for the northern lights, and we would see this even as far south as Juneau. They feel otherworldly, these bright dancing lights that come in waves and streams. Sometimes you get different colors, like whites and green and purples. I’ve been lucky enough to see them from my bedroom window, and a few times, I’ve seen come and go for about an hour.

COVID-19 in Juneau

What I really like about my job as an employee of the state’s Department of Education is that I get to travel in different parts of Alaska. But the pandemic put a stop to this, and I now work from home.

Currently, we have less than 20 active cases in Juneau. Although we’re not mandated to wear masks, we’re strongly encouraged to do so. When you take a stroll downtown, you’ll see half of the people wearing masks, although there are not a lot of people strolling downtown to begin with. Some restaurants are open for dine-in, but others have removed some tables to allow for more social distancing. At home, my family takes a lot of precautions. We always mask up and keep our masks by the door. We sanitize our groceries and wipe surfaces. We even sanitize our mail.

One can board a sea plane to explore other parts of southeast Alaska.

One can board a sea plane to explore other parts of southeast Alaska.

I suppose it helps that living in Juneau means embracing the outdoors. There are not a lot of cramped buildings where people would have difficulties keeping their distance. It also helps that it is relatively isolated. Among the U.S. capitals, Juneau is the only one that doesn’t have roads connecting it to the rest of the state; it’s been socially distancing even before social distancing was a thing.

In a way, this isolation is both a pro and a con: harder to get in, but equally harder to get out. Going places is one of the things I miss the most about the Philippines. There, I could easily go from Manila to Antipolo when I felt like it. Or when I’m in Aklan, where my parents are from, I could take a van and a boat ride just to meet up with friends in Boracay. I actually miss Manila traffic because that’s when I get to think. Before the pandemic, I’d take the long bus route home so I could stay on the road longer, but now I rarely leave the house. With my current work-from-home situation, I have no bus rides but I still have plenty of time to think. It makes me feel a little helpless to be here and away from my friends and relatives back home, because they seem so much further now more than ever.

But each day, it is enough to look out the window to where the mountains tuck us in, keeping us in place. It is enough to look across the dinner table to the people that keep me rooted. Here, they have a saying that goes, “You get to Juneau—by air, by sea, or by birth.” I got here by air, but I’m with my family now, and I have the rest of my life to look forward to.