Among the total number of overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) pegged at 2.2 million by the Philippine Statistics Authority in 2019, over 300,000 have so far been repatriated by the Department of Foreign Affairs because of pandemic-disrupted economies. Though this was deemed as the “biggest repatriation effort in the history of the DFA and of the Philippines” by Foreign Affairs Undersecretary for Migrant Workers’ Affairs Sarah Lou Arriola, the numbers indicate that majority of OFWs still remain in other countries.

Recent events have created stress for OFWs, who have their own struggles even without the health crisis. Psychologist Roselle G. Teodosio, owner of IntegraVita Wellness Center, explains that the OFWs’ primary source of stress is being away from their families. “The OFWs usually worry about the families they leave behind. This is especially true for those who have spouses and children. Another stressor is the culture shock or how to cope with the daily grind of living in a foreign land. The language barrier is a major stressor for OFWs aside from adapting to the new culture.” Financial obligations also create pressure as families and relatives tend to think OFWs make lot of money. “The family and relatives do not realize the sacrifices and hardships the OFW makes to be able to send money. Another stressor is their employers and co-workers. An abusive employer is not uncommon, and there may be multiracial co-workers. Different cultures tend to clash and lead to conflicts at the workplace.”

With the pandemic affecting economies and causing people to lose jobs, OFWs may be overwhelmed by multiple pressing problems. “There is fear, not only for the OFWs’ health, but also for the families dependent on them. Knowing that there is a greater risk for their families back home, there will be greater pressure on OFWs to retain their jobs,” says Teodosio. “There is the fear of a family member contracting the virus. The inability to be at the bedside of the sick family member will weigh heavily on the OFW. Also, the fear for one’s own health in a foreign land can be daunting. The OFW has to stay strong and not show the family back home that he is really scared since he thinks this will add to his family’s worries.”

As if these complications weren’t enough, now the holiday factor is thrown into the stressful mix. Because of the pandemic, OFWs who normally go home at this time to celebrate Chrismas with their families are forced to stay in their countries of employment. “Even the families of the OFWs feel the fear of their loved ones contracting the virus abroad or if they force themselves to come home. Another concern is if they go home, will they be able to go back to their jobs? So to make sure that there is a semblance of the security of tenure, then the OFW will remain where he is and not try to go back. The risk of getting infected is much higher if the OFW will try to come home,” shares Teodosio.

Christmas away from Family

Agnes, who has been working in Taipei for almost 5 years, comes home once a year during the holiday season. Like most Filipinos, she regards Christmas as the time to be with family. “My siblings and I are all working professionals, and Christmas is the best time to be in the same place altogether, as we usually take a two-week vacation leave from work. I spend most of my December with family, and since we’ve had a baby in the family—my younger brother’s— it’s been a lot more fun and special.”

Agnes admits that this is her second time to skip spending Christmas with her family. “Last year, I had to go to Italy for the wake of my fiance’s mom. I didn’t feel the impact of not being with my family on this important holiday because I was in a different country, and also needed to support my fiance and pay my respects. But this year, I’m definitely feeling the impact.”

Husband-and-wife OFWs Armie and Boyet in Qatar

Husband-and-wife OFWs Armie and Boyet in Qatar

Because of the nature of their jobs, Armie and Boyet who have been working in Qatar for 9 years don’t really get to go home during the holiday season. “That’s a busy time in the office,” shares Armie. “So we go home usually in April or May. But we didn’t get to do that this year because of the pandemic. So we thought we’d go home in December for a change—but that plan fell through as well.”

Still, spending Christmas away from her children and her 80-year-old mom for almost a decade has taken a toll on Armie. “It gets sadder each year. Sometimes, I hear a piece of music that reminds me of home, and already, I get emotional. There’s this deep longing to have our family together. When my husband and I first arrived here, we missed our family, but there was the novelty of discovering a new place and culture. Now, we just simply miss our family.”

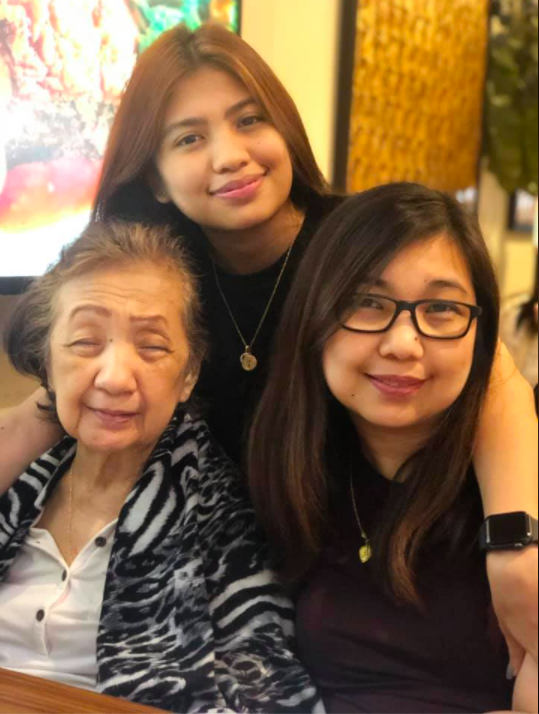

Armie with her daughter and her 80-year-old mom

Armie with her daughter and her 80-year-old mom

Increased Anxiety and Worry

Affirming what Teodosio mentioned, Agnes confesses the stress and anxiety she experiences at work is compounded by the pandemic. “I know I have the choice to not tune in to the news, but I always worry about the effects of the government’s ineptitude on my family and loved ones. I sometimes think I may be getting too emotional and overreacting, but I’ve been feeling like this for quite a while. It’s hard to be in a different country with no support system.”

Even if she’s able to go home, Agnes would rather stay in Taiwan for several reasons. “Although my host country has handled the pandemic well, no one knows if you’ll be able to contract the virus in transit. I don’t have enough leave credits to do a long-period quarantine, and I certainly don’t want to spend Christmas in quarantine.” Though her family understands her decision, Agnes can’t help getting emotional. “The knowledge that I can’t be with my family on this important holiday is making me feel depressed. We sometimes have video chats and I’ve brought up the topic of missing them a lot especially in these stressful times, and they’ve been supportive to a certain extent. Nevertheless, it’s still a painful decision even if it’s a necessary one.”

Armie and Boyet with their kids in 2018

Armie and Boyet with their kids in 2018

Though Armie worries about her family contracting the disease, a temporary setback came in the form of her husband’s 5-month unemployment. “He works in a gym, which shut down during the pandemic. The gym is back in business now, but during those 5 months, I worried about making ends meet. Somehow, we did it by cutting back on expenses.”

November brought Typhoon Ulysses, which submerged their house in Bulacan. “My kids and my mom didn’t have electricity and drinking water for several days. I asked help from friends in the Philippines, who thankfully helped them out. Now, my kids are busy with house repairs.” Though her children are used to Armie and Boyet’s absence, Armie confesses that her heart broke when her husband asked them what else they needed. “My kids replied, ‘You. We need you both. Please come home.”’

Coping this Holiday Season

The combined challenges of the pandemic and the holiday season may be difficult, but they can be conquered. Our interviewees offer these tips:

Stay grounded. “OFWs need to be resilient during these trying times. Focus on the things that they can control such as their thoughts, emotions, reactions and behavior. So in a time of pandemic, they can do their part in keeping safe by following safety protocols,” says Teodosio.

Find a support group. While taking a leave from work to “unplug from the stress,” Agnes is going to meet up with Pinoy friends in Taiwan. “We’re planning to have Noche Buena together and watch the fireworks display on New Year’s Eve.”

Stay healthy. Agnes tries to cope by taking care of herself physically and mentally. She adds, “So when it’s safe to travel, I’ll be in a better state and be able to make up for lost time.” Teodosio advises OFWs to differentiate between good and bad anxiety. “Some anxiety may be productive; this is what makes us wash our hands often and socially distance ourselves from others and keep our masks on,” she explains.

Focus on the present. The OFW needs to take one day at a time. “Excessively worrying about the future for himself or his family can sometimes paralyze a person with fear,” says Teodosio. “Becoming aware and mindful of all his thoughts and feelings can be very helpful in managing these emotions.”

Connect with family. Armie and Boyet make it a point to virtually share the annual Noche Buena with their family. “I plan their meal, take care of the budget, and make sure they decorate the house. When midnight strikes, Boyet and I eat with them via video chat,” shares Armie. Teodosio encourages OFWS to maintain constant communication. “Trying to weigh the pros and cons of coming home can help the OFW and their loved ones in understanding what is more important to them—the health of the OFW or being together during Christmas. Having the patience for one another and thinking of what is best for everyone will help the families cope in these trying times.” Agnes affirms this: “Sometimes I feel helpless, but at least with the chats and messages, there’s still something I can do even if it’s a small thing.”

If you’re anxious or depressed, don’t hesitate to reach out to the following:

- Roselle Teodosio (psychologist) – 09166961223 and 09088761223 or email: selteodosio@gmail.com

- National Center for Mental Health Crisis – 09178998727

- Philippine Mental Health Association – 09175652036

- Philippine Psychiatric Association – 09189424864

Mano po, Ninong

Mano po, Ninang

Narito kami ngayon

Humahalik sa inyong kamay

Salamat, Ninong

Salamat, Ninang

Sa aginaldo pong inyong ibinibigay

This timeless Christmas song by lyricist Ador Torres and composer Manuel Sr. Villar illustrates how popular godparents are during the holiday season, particularly in the aspect of gift-giving. During this time, jokes about being hunted down by a deluge of aginaldo-seeking godchildren are common, as if giving cash or gifts is the sole duty of the ninong or ninang. But is this really all there is to being a godparent?

Godparents, a brief history

According to Suzanna Roldan, who teaches Sociology and Anthropology at the Ateneo de Manila University, the ninong and ninang are part of the “compadrazgo relationships”, which came with Christian rituals such as baptism, confirmation, and marriage introduced by Spanish colonization. Our forefathers readily accepted the compadre/comare concept because even before the Spanish came, they had already been marking life events with rituals and social sanctions. “Anthropologists studying kinship systems observe that we consider who our relatives are based on biological, social and cultural ties. In categorizing who our relatives are, we trace blood lines, adoptive kin and kin through marriage or in-law relationships,” says Roldan. “There is one category of relatives that extends the notion of family. These are called fictive kin, or kinship established through rituals found in many, if not all, societies. In our case, the compadrazgo system is our way or reinforcing existing close kin or close social connections with people not necessarily our relatives.”

While godparents serve as witnesses to their godchildren becoming part of a religious community or a sanctioned marriage, the ninong or ninang also take on the role of spiritual guides. “If parents perished, godparents are expected to help in the spiritual formation of the child. We want godparents who can raise children as good Christians, or in the case of godparents to a couple, they can give spiritual advice on how to nurture good marital or parental relations. But this goes beyond spiritual formation and extends to the actual care of a child when the parents are unable to fulfill parental duties due to death, work, or moments when parents have to be apart from their children,” explains Roldan.

Photo by Denise Lazaro

Photo by Denise Lazaro

Selection of godparents

Until now, parents usually choose reliable godparents who are good role models, and have child-rearing values aligned with their own. Social proximity or close ties with godparents also plays a role. Roldan elaborates, “Parents select someone who is very close to the family or has regular interaction with them at the moment of selecting who the godparent would be. Our ninong and ninang are often siblings of our parents, playmate cousins, or our barkada from childhood whom we know we can entrust our children to in case something happens to us.”

Sometimes, economic reasons also play a part in the selection. “Some parents select well-known, high-status ninong and ninang whom one can turn to in times of need—even if they do not have a strong personal relationship with those individuals.” These include political figures, wealthy members of society, or someone who has achieved high occupational positions that indicate status.

Being a Godparent in Modern Times

Nowadays, it’s common to see godparents arrive in multiple pairs, crowding around the wed couple or the baptized child because of their sheer number. It’s a stark difference from decades ago, when a pair of godparents was enough to stand witness to religious rituals. As to why this has happened, Roldan offers this explanation: “Perhaps, it may be related to having less children these days compared to before. In the past, parents had more children, so they made sure to assign worthy godparents for all their children.”

Sometimes, the reason lies in having a big social circle. “For those with large friend groups and with one or two children, parents have to name more godparents per child so as not to exclude and hurt the feelings of their friends. Still, there are some who intentionally pick several godparents to compensate for the costs of the celebration, or expand the circle of elders they can approach for advice.”

Despite this practice, Grace, who has 10 godchildren, strives to fulfill her role. “I don’t get to talk to all of them except for my nephew who’s also my inaanak, but I do talk to their parents regularly. I know that most children see — and even expect — their godparents to give them gifts during Christmas and their birthdays. I think that’s okay especially when they’re young. That was how I saw my godparents too when I was a kid.”

Jason, who has about the same number of inaanak, shares that he only gets to interact with godchildren whose parents he’s still in contact with. “If I get to hang out with their parents, I also get to see my godchildren. I make small talk, maybe give cash. But now with social media, I can ask how they are from time to time. As a ninong, I look out for their welfare.”

Grace sees herself as a co-parent, ensuring that her godchildren grow up properly. She expects this same dedication from the godparents she’d chosen for her child. “There’s a saying, ‘It takes a village to raise a child’. It’s not easy to be a parent. As much as we want to provide for our kids’ mental, physical and emotional needs all the time, we can’t do it alone. And that’s where the ninongs and ninangs we have chosen, come in. After all, most of them are our childhood friends, high school and college buddies or our closest colleagues. They were there during our first crush, first heartbreak, and other milestones. So it only follows that as we go through this parenting journey, we go through it with them.”

Jason, 2nd from left, poses with his goddaughter Maya during her baptism.

Jason, 2nd from left, poses with his goddaughter Maya during her baptism.

The pandemic may discourage or even prohibit face-to-face interaction among godparents and godchildren, but phone calls, text message and online social platforms still make close communication possible all throughout the year. “Social support, particularly gift-giving during the holidays will continue. People shop online, send presents through various delivery modes. Ninangs and ninongs may send cash through online banking— at least for some sectors of society who are not affected by unemployment woes during the pandemic. We can expect more practical exchanges through social networks, or donations made instead of presents given during the pandemic,” Roldan ends.

To learn how you can enjoy a happy yet safe Christmas celebration during the pandemic, watch Be Safe: Pagiging Ligtas ngayong Holiday Season.