Latest data from the Department of Health (DOH) stated that at least 2.6 million Filipinos have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19. According to herdimmunity.ph, this is only 3.76% of the 70-million population the government aims to vaccinate this year to achieve herd immunity. The website says that at the current average rate of 216,451 daily vaccinations, herd immunity will be reached in 1.6 years, or in February 2023. For us to achieve herd immunity by the end of the year, the government needs to ramp up its vaccination 3.3 times its current rate.

Herd immunity or population immunity is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the “indirect protection from an infectious disease that happens when a population is immune either through vaccination or immunity developed through previous infection.” To better understand how we can reach this goal faster, the pilot online episode of Panayam sa Panahon TV featured the experts—health reform advocate Dr. Anthony Leachon and Dr. Noel Bernardo from the Philippine Red Cross.

(photo from Quezon City Hall’s Facebook page)

(photo from Quezon City Hall’s Facebook page)

Why PH is falling behind in the global vaccination drive

When the COVID-19 vaccines still weren’t available, governments resorted to lockdowns to stop the spread of disease. But now, countries like the United Kingdom and the United States have freed up their economies, thanks to systematic and rapid vaccination programs. In a recent segment of Panahon TV called Buhay Pandemya, which featured a Filipino caregiver in Jerusalem in Israel, maskless locals can be seen flocking to the streets and celebrating the return of normalcy. Israel was one of the countries that started their vaccination early, which began last December 2020.

But the scenario in the Philippines is a different story. Though cases in the National Capitol Region (NCR) have been somewhat contained, other areas are experiencing surges. Lockdowns and quarantines are still in place, keeping the economy from fully recovering. If we already know the tried-and-tested formula of mass vaccination as the main key to herd immunity, why then are we still behind in the immunization drive? Our experts chalked it up to three main reasons.

- Lack of vaccine supply

Based on Our World in Data’s latest report, the Philippines ranks 8th among the 10 ASEAN countries in terms of vaccine rollout. During the interview, Dr. Bernardo expressed surprise over his discovery that out of the 3,700 approved vaccination sites in the country, only 1,700 are active. “Based on my experience on the ground with the different LGUs and the bakuna centers of the Philippine Red Cross, a big factor is the lack of vaccines,” he said in Filipino. “Bakuna centers don’t receive enough vaccines. Other LGUs (local government units) can only operate half-days.” Dr. Leachon was quick to agree. “If you don’t have vaccines, it doesn’t matter if you have vaccination sites. People will still have no access to vaccination.”

- Lack of organization

With data gathered from DOH, the National Task Force Against COVID-19, the Inter-Agency Task Force and news outlets, Herdimmunity.ph states that we currently have over 17 million vaccine doses, “enough to fully vaccinate 12.47% of the target population.” If such is the case, why is the vaccination still slow?

Dr. Leachon pointed out that LGUs have varying levels of governance, with some more organized than the others. Because best practices are not adopted by all LGUs, they also have varying levels of success, making it harder for the country to reach herd immunity.

Meanwhile, Dr. Bernardo said that we should attack the issue with a “system approach”. He cited how a simple step such as securing a vaccination schedule has become problematic. “People shouldn’t have to walk in like chance passengers. When we schedule them, we know that number one, they fully consent to the vaccination. Second, they should know their vaccine brand so they can manage their expectations. That way, we avoid overcrowding. Third, our supply should cope with our demand. If people leave the site disappointed because of the hassle or lack of vaccine, then they will recount their bad experience to others. But if their experience is positive, others will be motivated to be vaccinated.”

In January this year, a Pulse Asia Survey resulted in 4 out of 10 Filipinos not wanting to get vaccinated. According to Bernardo, the survey was repeated in March. This time, the figure climbed up to 6 out of 10 Filipinos refusing vaccination. “There must be something about the people’s experience in the bakuna centers that increased hesitancy—which we must address right away. Because even if the government promised a flood of vaccines eventually coming in, will people agree to be vaccinated?”

- Vaccine Hesitancy

According to DOH, 9% or over 100,000 of vaccinees who received their first dose missed out on their second dose. According to Dr. Leachon, apart from disorderly systems that discouraged Filipinos, this may be also attributed to the lack of information, leading to decreased awareness. “Maybe they don’t know where they will go to for their second dose. Different vaccine brands have different durations between the two doses. Vaccinees should be given a checklist that includes all the info they need, including when they should return.”

Leachon also suggested massive info campaigns on the possible adverse effects of the vaccine, and the mode of registration. “Online registration is very difficult for the elderly and the poor. Why should we make it hard for them? We need to have a faster registration process.” Another common complaint among registrants is the slow response of LGUs.

Recently, the issue of vaccine brands became even more heated when hundreds of Indonesian health workers became infected with COVID-19 after being fully vaccinated with Sinovac. Recently, 10 Indonesian doctors died despite their complete inoculation with the Chinese vaccine. Until now, China has not provided large-scale data on Sinovac’s effectiveness against the Delta variant. “Our life is all about choices,” Dr. Leachon said. “We choose our spouse, clothes, food. So, it’s even more important to choose what is injected into our bodies. When we don’t give people choices, we’ll have a hard time convincing them to get vaccinated.”

According to WHO, the Sinovac vaccine, in a phase 3 trial in Brazil “showed that two doses, administered at an interval of 14 days, had an efficacy of 51% against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection.” With vaccine brands such as Pfizer and Moderna having an efficacy of 90% or more, some Filipinos are thinking twice about being inoculated with Sinovac. “About 70% of our vaccine inventory is Sinovac. What we’ve seen in Parañaque and Manila wherein residents flocked to the vaccination sites that gave out Pfizer is a sign that Filipinos are brand-conscious. They know their health is on the line. They value the quality, efficacy and safety of the vaccine,” Leachon said.

“Bakuna bus”—a partnership of the Philippine Red Cross and UBE Express

“Bakuna bus”—a partnership of the Philippine Red Cross and UBE Express

Ways to improve the vaccination drive

Once the main issue of vaccine supply is addressed, our interviewees suggested the following to ramp up our vaccination drive:

- Prioritize urban areas that drive the national economy.

ABS-CBN Data Analytics Head Edson Guido recently tweeted that though COVID-19 cases in NCR are decreasing, only 7.4% of its population are fully vaccinated. Dr. Leachon suggested that prioritizing the NCR Plus Bubble can help the country achieve herd immunity faster. “We shouldn’t spread the vaccine supply thinly across the country, especially those with no cold-chain facilities. For example, we’re expecting 40 million doses of Pfizer, which will fully vaccinate 20 million people. It’s better to prioritize super metro areas like NCR Plus, which has a population of around 26 million—and 70% of that is 18 million. If herd immunity is achieved in NCR Plus, we can open our economy in time for December 2021.”

- Make vaccines more accessible.

Although mega vaccination sites may work, Dr. Leachon pointed out that these are available only in selected areas. He believes that small but multiple vaccination sites may be more efficient. “Mega vaccination sites are prone to bottlenecks and may be superspreading events. Vaccination sites should be convenient for the elderly and those with comorbidities. These sites should be many and close to residents, who can be vaccinated faster because they don’t have to worry about transportation. Because the crowd is spread out among multiple sites, waiting time is reduced.” Dr. Leachon suggested taking inspiration from successful countries, which mobilized malls, drugstores and other convenient stores which have cold-chain infrastructure in the vaccination drive.

Dr. Bernardo agreed that the solution lies in community-based vaccination sites. “We really have to bring the vaccine closer to our people, so they will be encouraged. If every barangay has a mini-vaccination site which can only accommodate 20 people a day, that can already make a big difference.” He also enjoined the government to give vaccination leaves for employees. “In bakuna centers I’ve visited, I asked those who weren’t able to get their second dose what happened. They told me it’s because they couldn’t file a leave. We have to consider living factors like this.”

To help more Filipinos be vaccinated, Red Cross Philippines has partnered with UBE Express in employing mobile vaccination buses to reach far-flung areas that do not have cold-chain facilities. “We are ready to partner with national agencies, LGUs, NGOs and private sectors to maximize this initiative and utilize all the logistical support that Red Cross could offer. When the vaccines arrive, we will go to places not accessible to health workers and NGOs.”

- Strengthen governance.

One important aspect of good governance, especially in our country, is disaster preparedness. Currently, we are in the middle of the rainy season, which may pose challenges in the vaccination drive. “First, vaccination programs are usually done in open courts, gyms and other large open spaces, which have good ventilation. But when it rains, these outdoor areas will be affected,” Dr. Leachon explained. “Second, you need to separate evacuation centers for typhoon victims, isolation and quarantine facilities, and vaccination sites. Because the moment people from these areas mix, this can be super-spreading event.” Another concern is power outages that may affect cold-chain facilities.

Government responsiveness is also important in gaining public trust and cooperation. “For example, we know that the reason why the cases are not going down is because we lack contact tracing. But the governments don’t respond to this. The same way with surveys done by SWS and DOH, which showed the participants’ preferred vaccine brands and their perceived effects. You have to execute a program based on what the citizens want, or else you will be doing the same thing all over again, but expecting a different result,” said Dr. Leachon.

Marmick Julian, a proud vaccinee in Parañaque, displays his injected arm. (photo by Robi Robles)

Marmick Julian, a proud vaccinee in Parañaque, displays his injected arm. (photo by Robi Robles)

Achieving herd immunity

Dr. Bernardo believes that promoting vaccine confidence is an important step toward herd immunity. “The first vaccine brand we received should’ve been the best and most trusted. But a lot of doubts and issues were involved in our first vaccine—which was one of the main reasons of vaccine hesitancy.” To promote vaccine confidence, Dr. Bernardo stressed the need for better communicators. “There was a comms group that suggested that we relate vaccination to family. When you get yourself vaccinated, it’s a sign of love for your family and friends.”

As to achieving herd immunity this year, Dr. Bernardo was skeptical but hopeful. “We need 500,000 vaccinations a day if we want to have a happy Christmas this year.” Meanwhile, Dr. Leachon still emphasized the importance of vaccine efficacy. “We can only achieve herd immunity when the vaccines from Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca arrive. We need to step up to the plate in the next 3 months and revisit our strategies,” he ended.

Watch Panayam sa Panahon TV’s Herd Immunity: Kailan at Paano Natin Ito Maaabot?

As the Philippines continues its COVID-19 vaccination drive, its active cases have spiked past 86,000, including the country’s highest single-day increase since the pandemic began. A year after lockdown was declared, the health system is, once again, overwhelmed.

While the Department of Health’s hospital referral system is swamped with calls about new cases, 30 hospitals in NCR have declared full bed capacities for COVID-19 patients. COVID-19 variants have been detected in all cities in Metro Manila, prompting the government to place the area as well as Cavite, Laguna, Rizal and Bulacan in a bubble from March 22 to April 4. Within this period, only essential travel will be allowed into and out of these places.

More than ever, faster and more efficient processes need to be in place, especially since only over 500,000 have so far been inoculated—less than 1% of the 70 million targeted to achieve herd immunity this year. To better understand this issue, we discuss key points of an online discussion held by the Women’s Business Council of the Philippines, featuring health-sector heavyweights such as Former Health Secretary Dr. Esperanza Cabral; Dr. Susan Pineda-Mercado, director of Food Systems and Resiliency at the Hawaii Institute for Public; and Dr. Tony Leachon, chairman of Kilusang Kontra-COVID.

The Parañaque government began its vaccination of senior citizens last March 22, 2019

The Parañaque government began its vaccination of senior citizens last March 22, 2019

The Need for Vaccines

In the online talk held last February, Dr. Cabral expressed her pro-vaccination views, stating how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) listed vaccination as one of the 10 greatest public health achievements of the 21st century. “Vaccines have gone to develop into the most life-saving medical advancement in history,” she said.

Meanwhile, Dr. Mercado explained how the COVID-19 vaccination could protect one’s health. “You get a tiny bit of the virus, and that will stimulate the development of the antibodies. It helps you recognize the enemy because if you get natural exposure, your disease will not be moderate or even severe.”

With mass vaccination enabling majority of the population to develop a considerable degree of immunity against COVID-19, Dr. Cabral stated the following possible benefits:

- Protects us, our loved ones and communities from disease and death

- Enables us to reopen our society

- Prevents our health care workers from being overwhelmed

- Frees us up to address the non-COVID diseases we suffer from

“Why are vaccines important to us? They are important to us because if there is a vaccine for a disease, it will prevent that severe disease and death from it,” Dr. Cabral said. “It will prevent symptomatic disease and importantly, it will also prevent the transmission of disease to others.”

Dr. Grace Pagayon-Uy received her first jab of AstraZeneca as part of the QC government’s vaccine rollout for health care workers this week.

Dr. Grace Pagayon-Uy received her first jab of AstraZeneca as part of the QC government’s vaccine rollout for health care workers this week.

The Importance of Starting Early

But as Dr. Mercado stated, mass vaccination does not guarantee an immediate victory against the virus. The changes are likely to be felt gradually, which is why early intervention is key. Dr. Cabral enumerated these results of Israel’s early vaccination drive, which started in January:

- COVID-19 vaccine was 98.9% effective in preventing deaths and hospitalizations.

- COVID-19 vaccine was 98% effective in preventing infections that prompted fever or breathing problems.

- Infection rate declined by 95.8% among those who received two doses of the vaccine.

To guarantee early vaccination, Dr. Leachon shared that acquisition of vaccines should start as early as the phase 2 of clinical trials—which is what Vietnam, China, India and South Korea did. He presented a projection of good economic growth among these countries. Meanwhile, poor pandemic response resulted in the plummeting economies of the US, Brazil and the UK.

AstraZeneca vaccine arrive in the Philippines from the COVAX facility last March 4. (Photo from National Task Force Against COVID-19)

AstraZeneca vaccine arrive in the Philippines from the COVAX facility last March 4. (Photo from National Task Force Against COVID-19)

On the Flip Side: Anti-Vaxxers

The World Health Organization included “vaccine hesitancy” in one of the top global health threats in 2019. WHO stated, “Vaccine hesitancy – the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines – threatens to reverse progress made in tackling vaccine-preventable diseases. Vaccination is one of the most cost-effective ways of avoiding disease – it currently prevents 2-3 million deaths a year, and a further 1.5 million could be avoided if global coverage of vaccinations improved.”

WHO identified the possible reasons for vaccine refusal:

- Complacency

- Inconvenience in accessing vaccines

- Mistrust or lack of confidence

Throughout history, anti-vaxxers—the term used for those who oppose vaccines—have cited various side-effects from vaccines. These included infertility, brain damage, and most recently, autism, which some claimed were an effect of the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine for children. This resulted in a decline in MMR vaccinations, which, in turn, resulted in an emergence of measles and mumps in Europe and North America, which had not seen these diseases for many years. According to the CDC, studies have dispelled the claim linking vaccinations to autism.

Dr. Gladys Lacuna-Mendoza gets her first dose of Sinovac vaccine. According to Sec. Carlito Galvez, chief implementer of the National Task Force Against COVID-19, almost 24% of the country’s 1.7 million health workers have been vaccinated.

Dr. Gladys Lacuna-Mendoza gets her first dose of Sinovac vaccine. According to Sec. Carlito Galvez, chief implementer of the National Task Force Against COVID-19, almost 24% of the country’s 1.7 million health workers have been vaccinated.

Convincing the Skeptics

A recent survey from OCTA Research revealed that 46% of Filipinos are unwilling to get inoculated against COVID-19 even if the vaccine was proven safe and effective. To combat this massive vaccine hesitancy, Dr. Cabral urged the government to use “trustworthy and trusted talking heads, and use language that people can easily understand.” Messages should also be balanced and consistent, and widely reiterated across all platforms.

Dr. Leachon even warned that future travel might require COVID-19 immunity passports. “This is important to economic recovery and that’s why we need to have vaccination. The Philippines will be isolated from the rest of the world if we will not be vaccinated— tourists will hesitate to come, the international business people will not travel, Filipinos may not be given passes to travel abroad, thus curtailing business activities and even family leisure and travel. Our competitiveness will sink even further in the rankings.”

But even with vaccination, Leachon said health measures should still be improved such as contact tracing, quarantine and isolation facilities, and even government messaging. “We should invest in health care so we can prepare for the next pandemic. We have to take better care of our health care workers.”

Still, even if public acceptance of vaccination improves, the slow arrival and rollout of COVID-19 vaccines remain a major hindrance. All the health experts in the online discussion agreed that right now, there is no room for complacency. To save lives and the economy, vaccination needs to be a priority. “The economy will never recover as long as the virus is not controlled. And if you don’t understand that, then we’re part of the problem,” ended Dr. Leachon.

Donna May Lina at Agay Llanera

Dahil buong mundo ay abala sa pagpuksa ng COVID-19, laging laman ng balita ang pagpapabakuna laban sa sakit na ito. Ayon sa Bloomberg, ang Estados Unidos ang nangunguna sa dami ng mga nabakunahan. Pumapalo sa halos 2.5 milyon ang natuturukan ng COVID-19 vaccine sa U.S. kada araw.

Simula nang inumpisahan ng Pilipinas ang vaccination drive nito n’ung March 1, higit sa 240,000 ang nabakunahan nang mga Pilipino. Ngunit bukod sa mabagal na pagdating ng mga vaccine, hadlang sa malawakang vaccination ang kawalan ng tiwala ng mga Pilipino sa vaccine. Ayon sa isang survey, 46% ng mga Pilipino ay hindi papayag mabigyan ng COVID-19 vaccine kahit na napatunayan itong ligtas at epektibo.

Kasaysayan ng Bakuna

Pinaniniwalaan na ang English physician na si Edward Jenner ang unang nagsagawa ng matagumpay na pagpapabakuna. Pagkatapos niyang turukan ng smallpox virus ang isang bata, nagkaroong ang pasyente ng immunity sa nasabing sakit. Nang nagkaroon na ng mass vaccination, tuluyan nang naiwaksi mula sa mundo ang small pox noong 1979.

Ayon sa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), mahalaga ang childhood vaccines o ‘yung mga bakunang ibinibigay sa mga sanggol at bata sa pag-iwas sa sumusunod na mga sakit:

- polio

- tigdas (measles)

- diphtheria

- pertussis (whooping cough)

- tigdas-hangin (German measles)

- beke (mumps)

- tetanus

- rotavirus

- Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

Ang mga bakuna ay nagbibigay proteksyon, hindi lang sa indibiduwal, kungdi pati rin sa buong komunidad.

Ano ang Herd Immunity?

Inilalarawan ng World Health Organization (WHO) ang herd immunity bilang indirektang proteksyon laban sa isang nakahahawang sakit. Maaaring magkaroon ng immunity ang isang populasyon mula sa pagpapabakuna o dati nang pagkakasakit. Dahil posibleng mabiktima ng COVID-19 nang higit sa isang beses, inirerekomenda ng WHO ang pagpapabakuna laban dito upang makamit ang herd immunity.

Para hindi dapuan ng matinding COVID-19 ang malaking bahagi ng populasyon, isinasagawa ng mga bansa ang malawakang vaccination. Herd immunity rin ang layunin ng pamahalaan ng Pilipinas kaya inanunsyo nito ang planong mabakunahan ang 70 milyong Pilipino sa loob ng isang taon.

COVID-19 Vaccination Plan sa Pilipinas

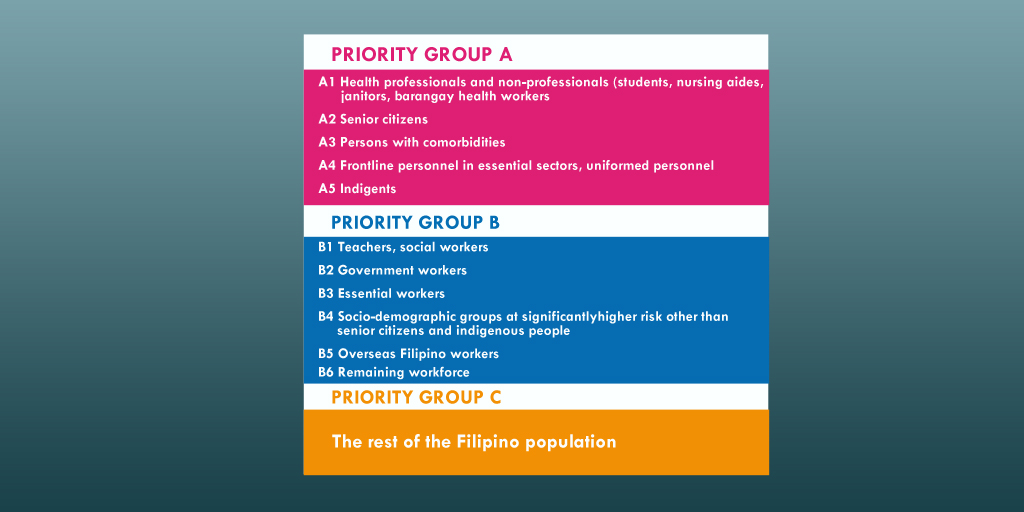

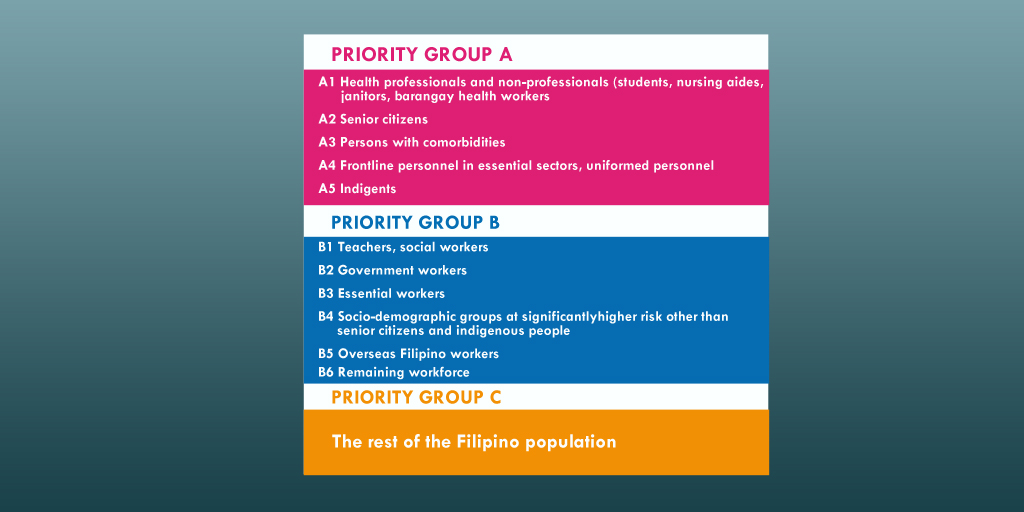

Noong Pebrero, inilabas ng Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID) ang priority list o ‘yung pagkakahanay ng mga mababakunahan.

Source: Philippine News Agency (PNA)

Source: Philippine News Agency (PNA)

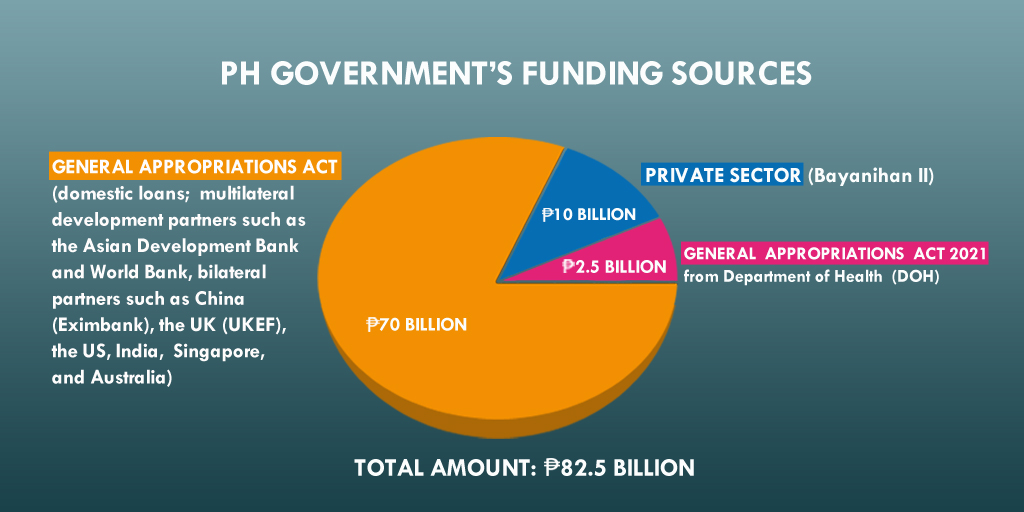

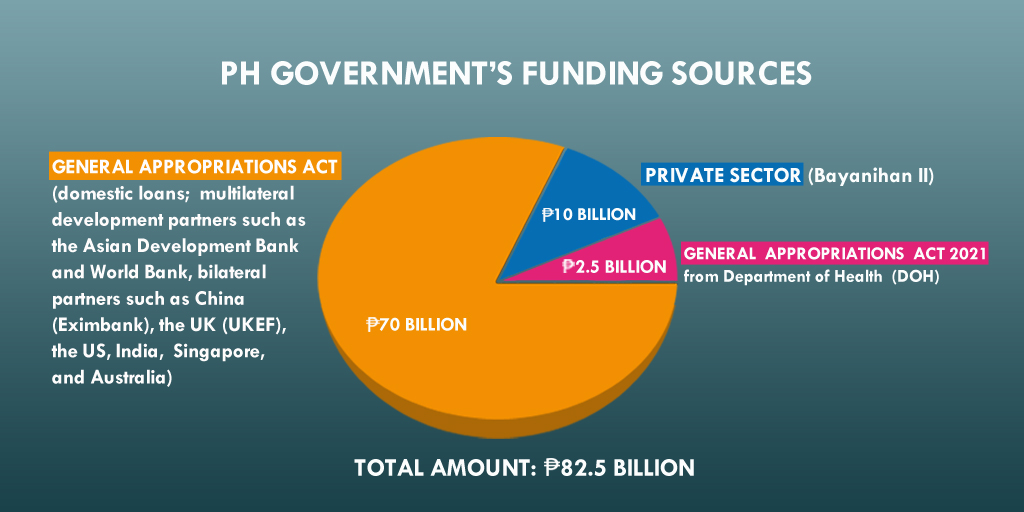

Ayon sa Philippine National Deployment and Vaccination Plan for COVID-19 Vaccines, nakakalap na ang pamahalaan ng ₱82.5 billion. Ilalan ito sa pagbili ng mga vaccine at iba pang mga gastusin sa pagbabakuna.

Source: DOH

Source: DOH

Nabanggit ni Department of Finance (DOF) Secretary Carlos Dominguez III na posibleng umabot sa ₱1,300 ang pagbabakuna sa bawat indibiduwal. Dagdag pa niya, mga 57 milyong Pilipino ang makikinabang sa ₱75-bilyong pondong inilaan ng pamahalaan sa pamimili ng mga vaccine. Ang natitirang populasyon ay paggagastusan ng mga LGU (local government unit) at pribadong sektor. Sa ilalim ng Bayanihan to Recover as One Act, pumirma ng kontrata ang lokal na pamahalaan, LGU at mga 300 pribadong kumpanya upang bumili ng 17 milyong dosis mula sa British pharmaceutical company na AstraZeneca. Ayon kay Joey Conception, ang Presidential Adviser for Entrepreneurship, kalahati ng mga dosis na bibilhin ng pribadong sektor ay ibibigay sa gobyerno, habang ang kalahati ay mapupunta sa mga empleyado ng mga kumpanya.

Nationwide Vaccination Drive

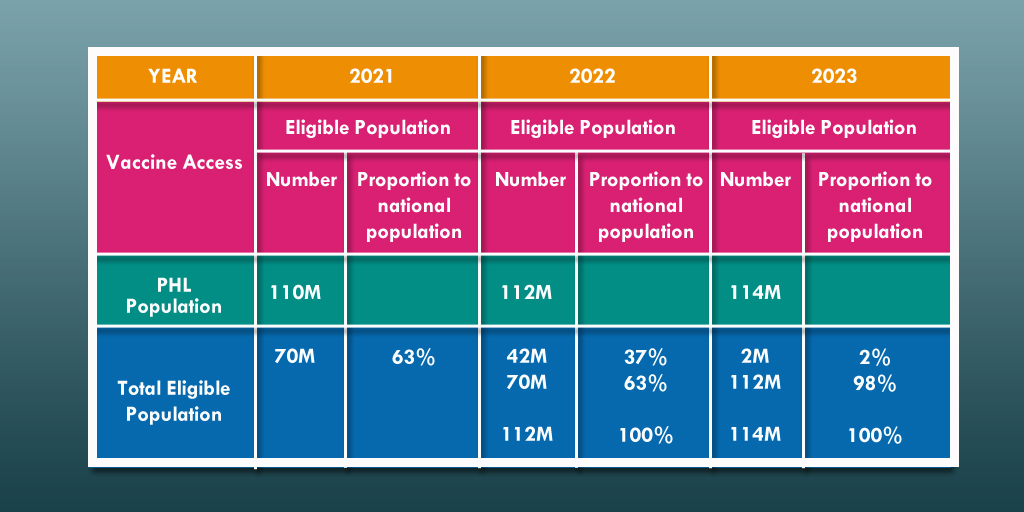

Sources: DOH, WHO, PNA

Sources: DOH, WHO, PNA

Higit sa 480,000 dosis ng AstraZeneca vaccine ang ibinigay ng COVAX facility sa Pilipinas. (Photo: National Task Force Against COVID-19)

Higit sa 480,000 dosis ng AstraZeneca vaccine ang ibinigay ng COVAX facility sa Pilipinas. (Photo: National Task Force Against COVID-19)

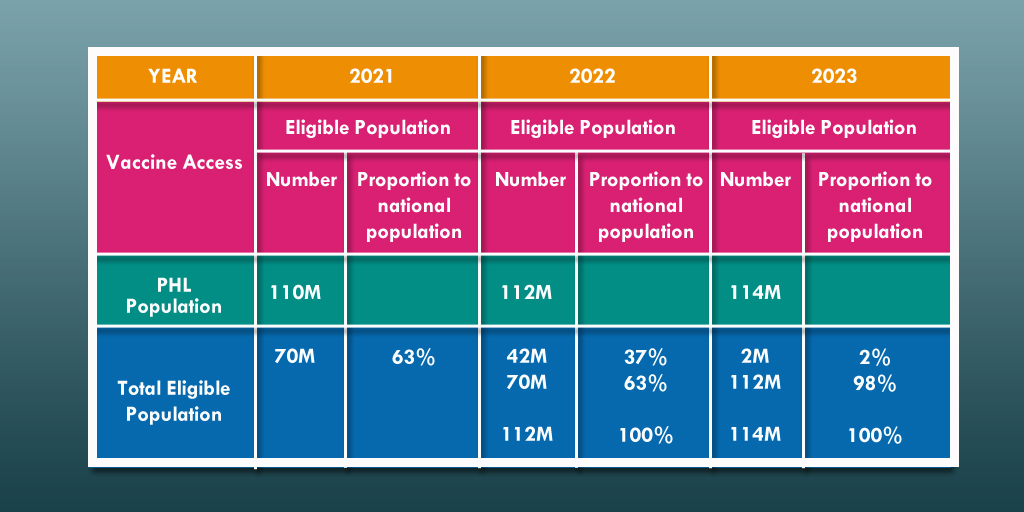

Base sa tinatayang datos ng paglago ng populasyon mula sa Philippine Statistics Authority, bumuo ang pamahalaan ng three-year vaccination plan mula 2021 hanggang 2023. Inaasahan na sa 2022, maaari nang mabakunahan ang mga 16 years old pababa, habang meron nang COVID-19 vaccine para sa mga sanggol sa 2023. Ang mga binakunahan ngayong 2021 ay bibigyan pa ng booster shots sa susunod na mga taon.

Source: DOH

Source: DOH

Pagkamit ng Herd Immunity

Kahit hindi pa alam ng WHO ang eksaktong porsyento ng isang populasyon na dapat mabakunahan upang makamit ang herd immunity, layunin ng pamahalaan ang mabigyan ng COVID-19 vaccine ang 70 milyong mga Pilipino ngayong 2021. Pero dalawang dosis ang kailangan para makumpleto ang pagpapabakuna— ibig sabihin, 140 milyong dosis ang dapat maiturok ngayong taon.

Base sa mga bilang na ito, dapat bilisan ng pamahalaan ang pagbabakuna para magkaroon ng herd immunity sa bansa—lalo na’t kailangang kailangan na ito ng ating ekonomiya.

Matagal pang haharapin ng bansa ang pandemya, at hindi pa natin alam kung kailan ito matatapos. Ngunit isang bagay ang maliwang: hangga’t hindi pa nababakunahan ang 70 milyong mga Pilipino, kailangan ng ibayong pag-iingat ngayong tumataas muli ang mga kaso ng COVID-19 sa bansa.

Tumatakbo ang oras, pero habang wala pang bakuna ang karamihan ng mga Pilipino, dapat sundin ang mga hakbang upang masiguro ang pansariling kalusugan at kaligtasan. Sa ganitong paraan pa lang natin maiiwasan ang sakit na patuloy na dumadagdag sa 2 milyong bilang na namamatay sa buong mundo.

Donna Lina with Agay Llanera

With the whole world racing to beat the pandemic, COVID-19 vaccinations are at the top of the global news pile. According to Bloomberg, the United States tops the list of having the most vaccinations so far at the rate of over 2 million doses per day.

Since the start of the Philippines’ vaccination drive last March 1, the latest tally of total vaccinations is now over 114,000. Besides the delayed arrival of vaccines, another hurdle the country’s mass vaccination faces is the Filipinos’ reduced confidence in vaccines. According to a recent survey, 46% of Filipinos are unwilling to get inoculated against COVID-19 even if the vaccine was proven safe and effective.

A Brief History of Vaccines

English Physician Edward Jenner is widely recognized to have made the first vaccination in 1796. After inoculating a child with smallpox virus, the vaccinee developed an immunity to the disease. Mass immunization following the development of the smallpox vaccine led to the disease’s global extermination in 1979.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) acknowledges the crucial role of childhood vaccines in preventing the following diseases:

- polio

- measles

- diphtheria

- pertussis (whooping cough)

- rubella (German measles)

- mumps

- tetanus

- rotavirus

- Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

For communicable diseases, vaccines act as extra protection for the body and the entire community. To get this kind of protection, a community must achieve herd immunity.

What is Herd Immunity?

Herd immunity or population immunity is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the “indirect protection from an infectious disease that happens when a population is immune either through vaccination or immunity developed through previous infection.” WHO makes it clear that it supports herd immunity against COVID-19 through vaccination.

This is achieved through mass vaccination, enabling majority of the population to be immune to the disease. Scientists are still researching how much of the population needs to be inoculated for herd immunity against COVID-19 to take place. In the Philippines, the government announced its plans to vaccinate 100% of its adult population or about 70 million Filipinos.

COVID-19 Vaccination Plan in PH

Last February, the Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID) finalized the priority list for the COVID-19 vaccination drive.

Source: Philippine News Agency (PNA)

Source: Philippine News Agency (PNA)

According to the Philippine National Deployment and Vaccination Plan for COVID-19 Vaccines, the government has accumulated ₱82.5 billion to cover costs of procuring vaccines, logistics, distribution and monitoring.

Source: DOH

Source: DOH

With vaccination costs pegged at ₱1,300 per individual according to Department of Finance (DOF) Secretary Carlos Dominguez III, around 57 million Filipinos will benefit from the nearly ₱75-billion funds allocated by the government for vaccine acquisition. The remaining individuals are to be covered by the local government units (LGUs) and the private sector. Under the Bayanihan to Recover as One Act, the national government, local government units (LGUs) and about 300 Philippine companies signed an agreement with British pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca to procure 17 million vaccine doses. In this article, Presidential Adviser for Entrepreneurship Joey Concepcion said that half of the vaccine doses will be given to the national government, while the remaining half are for the companies’ workforce.

Nationwide Vaccination Drive

Sources: DOH, WHO, PNA

Sources: DOH, WHO, PNA

Over 480,000 doses of AstraZeneca vaccine arrive in the Philippines from the COVAX facility. (Photo from National Task Force Against COVID-19)

Over 480,000 doses of AstraZeneca vaccine arrive in the Philippines from the COVAX facility. (Photo from National Task Force Against COVID-19)

With population projections from the Philippine Statistics Authority, the government developed a three-year vaccination plan from 2021 to 2023. The roadmap assumes that by 2022, those 16 years old and below may be allowed to take the vaccine, and that by 2023, newborns can be inoculated against COVID-19. Those who’d taken the shots in 2021 will be given booster shots in the succeeding years.

Source: DOH

Source: DOH

Achieving Herd Immunity

Though WHO emphasizes that “the proportion of the population that must be vaccinated against COVID-19 to begin inducing herd immunity is not known,” the Philippine government’s goal of vaccinating 70 million Filipinos this 2021 aims to achieve herd immunity. Because each vaccination requires two doses, 140 million vaccine doses need to be rolled out in a year.

Based on such figures, the government needs to ramp up its vaccination drive to achieve herd immunity, and enable the country to recover both from the health and economic crises.

The country’s battle against the pandemic is still unfolding but one thing remains clear: until the crucial number of 70 million have not been vaccinated, Filipinos need to be on their toes as cases continue to surge.

Time is of the essence, but with majority having no means for vaccination yet, basic health and safety measures are still the strongest defense against this disease which continues to add to the global death toll of over 2 million.