The new year is just around the corner, which means most people are making plans and resolutions to spark positive changes in their lives. By letting go of attitudes, habits and situations that no longer serve them, people are better attend to their needs, improving the quality of their lives.

One significant change some make is to literally move beyond their comfort zones—and by that, we mean changing their places of residence. According to a survey released by the Philippine Statistics Authority in 2012, internal migrants were at a whopping 2.9 million between 2005 and 2010. While 45.4% merely changed cities, more than half (50.4%) were long-distance movers who changed provinces. The latter movers came from Calabarzon at 27.7%, the National Capital Region (NCR) at 19.7%, and Central Luzon at 13%.

NCR is the top choice of migrants outside Metro Manila, as shown by the World Bank’s Philippines Urbanization Review in 2017. In the previous decade alone, the country’s annual increase of urban population was at 3.3%, making the Philippines as one of Asia-Pacific’s fastest urbanizing countries.

But what about the second-biggest population of long-distance movers who moved out from NCR? Their significant number shows that there are Filipinos who choose to trade the modern conveniences of city life for the slower-paced rural setting. We get to know some of these brave migrants, and the steps they took to make such a major change.

Layla Tanjutco

Layla Tanjutco

Current residence: Mangatarem, Pangasinan since 2018

Residence history: I was born and raised in Quezon City right up to when I started working in Makati. I eventually had to move away from our childhood home to be nearer my work. I was pretty much the city girl and enjoyed having everything accessible.

In 2007, I decided to try out the probinsya life with my family. We moved to Negros, in a house by the sea. I woke up to and was lulled to sleep by the sound of the waves— and I loved it. After about a year, I got pregnant with my second child. Just then, job offers in Manila started coming in, so I decided to move back to the city. My family followed, and we settled back in my childhood neighborhood.

Reason for moving to Pangasinan: I’ve been working from home full time. Meanwhile, my favorite cousin put up a farm in their family property in Pangasinan. My family and I would go for short visits and I would always enjoy my time there. My cousin needed help running the farm, and one of my sisters and I were getting really tired of the city life so we floated around the idea of moving to the farm for months before finally deciding.

Also, my kids were growing up and needed their own space. I needed my own space too and with how multi-bedroom rentals are in Manila, there was no way I could afford them. That and the fact that my sister and I can work anywhere as long as we have internet cemented our idea for the move.

Liwliwa Malabed

Liwliwa Malabed

Current residence: Bae, Laguna since 2016

Residence of history: I was born and raised in Ilocos Sur, and went to Manila to study in UP Diliman in 1997. Since then, I never left the campus, staying in dorms and rentals even after I graduated and took my master’s degree. When I became pregnant with my daughter, our family moved to Makati, and when we needed more space, we relocated back in Quezon City.

Reason for moving: I was coming home from a workshop I’d conducted near ABS-CBN. It was raining on a Friday before a holiday payday. I couldn’t get a cab or a free seat in jeepneys. My daughter was only a year old then, and in my desperation to go home, I started walking, hoping I could catch transportation along the way. But I only got inside a jeepney in Quezon City Circle, and even then, the vehicles weren’t moving. So I got off and ended up walking all the way to our house in Visayas Avenue, Quezon City. It was then I told my partner that we should move out of Manila.

We chose Laguna because my partner wanted to live somewhere near Manila. Because I’m a licensed teacher, I felt I could find a job anywhere. I also liked Laguna because I had fond memories of it—it was there I finished a part of my master’s thesis, and my older brother has been living in Los Baños since 2008. Knowing he was there was a huge plus because I knew I could count on him if we needed help.

Aya Tejido

Aya Tejido

Current residence: Antipolo, Rizal since 2009

Residence history: I have always been a Manila girl until I got married and moved to the borderline of Cainta and Antipolo in Rizal.

Reason for moving: My in-laws bought this house in the 1980s, and since it wasn’t being used, they suggested that we renovate it and live in it. My husband and I agreed because we didn’t have to pay rent. It didn’t occur to us that we would be far from everyone; we just wanted to have our own space without incurring so much cost.

Layla about to harvest vegetables in the farm

Layla about to harvest vegetables in the farm

What are pros of probinsya living?

Layla: I sometimes miss not having everything at the drop of a hat or being far away from my friends, but waking up to bird song or seeing the night sky peppered with stars, feeling closer to the earth and things that grow are things that I cherish and am very grateful for. Anywhere you live, there will be challenges, but I feel like my soul is calmer here. My sister and I would often joke that we’re having an eternal summer vacation. We used to just spend short vacations here; now, we live here and we love it no less, maybe even more.

Liwliwa: We enjoy each other as a family. Before the pandemic, we’d often hang out at IRRI (International Rice Research Institute) and UPLB (University of the Philippines Los Baños). The air is fresher, and we get to see fireflies. We like exploring other parts of Laguna; we’ve gone camping in Cavinti and Caliraya. Our diet has become healthier because we directly source from local farmers. I think it’s more peaceful and safer here, and the rent is much cheaper. Right now, we live in a 4-bedroom house with two bathrooms and a backyard—and the rent is a fraction of what we’d pay in Manila with the same facilities.

Aya: It’s less dusty here. In Manila, it would take only two days to get a thick film of dust in your room. Back when we didn’t have neighbors, we could see the mountain, which looked dramatic during sunrise. Even when it’s summer, we don’t feel the heat. Over the years, the area has gotten more developed, with more small hospitals and community malls with groceries, so it’s now convenient to live here.

Liwliwa and her daughter at the Makiling Botanic Gardens

Liwliwa and her daughter at the Makiling Botanic Gardens

What are the cons of probinsya living?

Layla: What we really found challenging to adjust to at first was the early time shops would close. In Manila, restaurants, bars and stores would be open late at night. Here, only 7-11 and the evening pop-up carinderias would be open beyond 8 p.m. During the pandemic, closing times became even earlier, and a lot of the small shops and eateries closed down for good. We didn’t use to have delivery services for the various cafes and restaurants that started popping up early last year, but now we do. We often had power outages and I never thought I’d consider owning a generator but here we are.

Liwliwa: To get to Los Baños, which is where all the action is, you take a jeepney that has to be full before it leaves the terminal. So even if we’re near Los Baños, travel time takes about an hour. Public transportation is a real challenge, especially when I get home late from the occasional gig in Manila. When that happens, I’d call my brother, who’d fetch me with his motorcycle. Eventually, my partner and I were able to buy a car, which allowed us to move around during lockdown.

Aya: I had to get used to the silence. As early as 4 a.m. in Manila, I’d hear jeepneys warming up their engines. Noise was a constant companion, even at night. Here, I only hear birds and the tuko. I found it weird at first.

In my area, traffic is a perennial issue because there’s only one road to take if you want to go to the city—and that’s the Marcos Highway. The problem is compounded when there’s roadwork along the highway. If we’re traveling out of the country, we have to book a hotel near the airport because there’s no way we can leave at a decent hour and arrive in time for our flight.

Mostly retirees live in our huge village, so one time, when my daughter was looking for playmates, we had to walk several streets before we found kids her age.

Aya in her backyard with a flourishing malunggay plant behind her.

Aya in her backyard with a flourishing malunggay plant behind her.

Are you happy with your decision to move?

Aya: We’re happy living here. If someone asked me advice about moving out of Manila, I’d tell them to always look for the nearest hospital, drugstore and grocery store. Since they would be living away from family, they need to know where to get their essential goods and services. Here, we learned to be self-reliant, especially when there’s flood. Our shelves have to be well- stocked all the time. Still, it’s more refreshing to live outside the city.

Liwliwa: When we made the decision to live in Laguna, I was ready for countryside living. I think we always idealize the province as a good place to bring up our families, but what matters more than the place is the people you’re be living with. I think our family will thrive wherever we end up because we get along with each other.

Layla: Living the probinsya life really drove home for me how we take many things in our life for granted. Whether you’re living in the city with the many conveniences that are easily accessible or here in the laid-back province, you don’t know what you have until it’s gone. We always feel like we’re missing something; we want what we don’t have, so much so that we forget what we do have at this moment. I am thankful I have the luxury of looking out my window and saying hello to a beautiful bird, or eating sweet, seedless papaya from our backyard tree in the same way I am thankful now for the many years I spent in the city, and eventually (when things are better) being able to go back there for a quick visit to see friends and the places I missed. Probinsya life really teaches you to slow down, take in as much of the view as you can, enjoy the little things every day, and be thankful for each one.

Among the total number of overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) pegged at 2.2 million by the Philippine Statistics Authority in 2019, over 300,000 have so far been repatriated by the Department of Foreign Affairs because of pandemic-disrupted economies. Though this was deemed as the “biggest repatriation effort in the history of the DFA and of the Philippines” by Foreign Affairs Undersecretary for Migrant Workers’ Affairs Sarah Lou Arriola, the numbers indicate that majority of OFWs still remain in other countries.

Recent events have created stress for OFWs, who have their own struggles even without the health crisis. Psychologist Roselle G. Teodosio, owner of IntegraVita Wellness Center, explains that the OFWs’ primary source of stress is being away from their families. “The OFWs usually worry about the families they leave behind. This is especially true for those who have spouses and children. Another stressor is the culture shock or how to cope with the daily grind of living in a foreign land. The language barrier is a major stressor for OFWs aside from adapting to the new culture.” Financial obligations also create pressure as families and relatives tend to think OFWs make lot of money. “The family and relatives do not realize the sacrifices and hardships the OFW makes to be able to send money. Another stressor is their employers and co-workers. An abusive employer is not uncommon, and there may be multiracial co-workers. Different cultures tend to clash and lead to conflicts at the workplace.”

With the pandemic affecting economies and causing people to lose jobs, OFWs may be overwhelmed by multiple pressing problems. “There is fear, not only for the OFWs’ health, but also for the families dependent on them. Knowing that there is a greater risk for their families back home, there will be greater pressure on OFWs to retain their jobs,” says Teodosio. “There is the fear of a family member contracting the virus. The inability to be at the bedside of the sick family member will weigh heavily on the OFW. Also, the fear for one’s own health in a foreign land can be daunting. The OFW has to stay strong and not show the family back home that he is really scared since he thinks this will add to his family’s worries.”

As if these complications weren’t enough, now the holiday factor is thrown into the stressful mix. Because of the pandemic, OFWs who normally go home at this time to celebrate Chrismas with their families are forced to stay in their countries of employment. “Even the families of the OFWs feel the fear of their loved ones contracting the virus abroad or if they force themselves to come home. Another concern is if they go home, will they be able to go back to their jobs? So to make sure that there is a semblance of the security of tenure, then the OFW will remain where he is and not try to go back. The risk of getting infected is much higher if the OFW will try to come home,” shares Teodosio.

Christmas away from Family

Agnes, who has been working in Taipei for almost 5 years, comes home once a year during the holiday season. Like most Filipinos, she regards Christmas as the time to be with family. “My siblings and I are all working professionals, and Christmas is the best time to be in the same place altogether, as we usually take a two-week vacation leave from work. I spend most of my December with family, and since we’ve had a baby in the family—my younger brother’s— it’s been a lot more fun and special.”

Agnes admits that this is her second time to skip spending Christmas with her family. “Last year, I had to go to Italy for the wake of my fiance’s mom. I didn’t feel the impact of not being with my family on this important holiday because I was in a different country, and also needed to support my fiance and pay my respects. But this year, I’m definitely feeling the impact.”

Husband-and-wife OFWs Armie and Boyet in Qatar

Husband-and-wife OFWs Armie and Boyet in Qatar

Because of the nature of their jobs, Armie and Boyet who have been working in Qatar for 9 years don’t really get to go home during the holiday season. “That’s a busy time in the office,” shares Armie. “So we go home usually in April or May. But we didn’t get to do that this year because of the pandemic. So we thought we’d go home in December for a change—but that plan fell through as well.”

Still, spending Christmas away from her children and her 80-year-old mom for almost a decade has taken a toll on Armie. “It gets sadder each year. Sometimes, I hear a piece of music that reminds me of home, and already, I get emotional. There’s this deep longing to have our family together. When my husband and I first arrived here, we missed our family, but there was the novelty of discovering a new place and culture. Now, we just simply miss our family.”

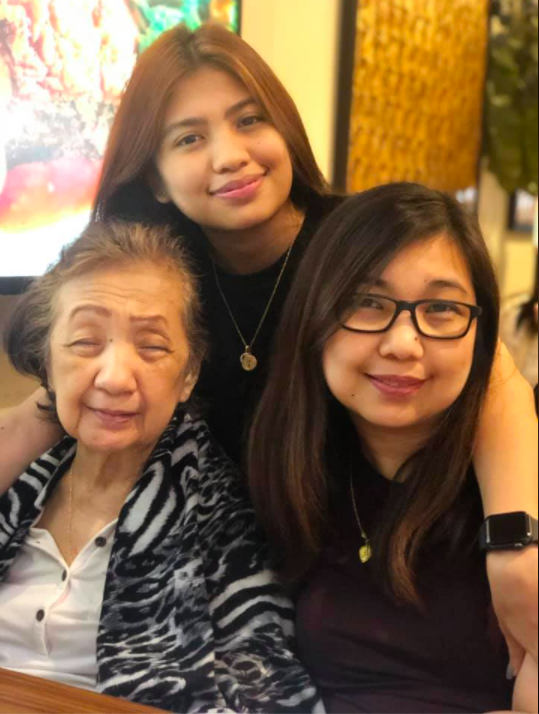

Armie with her daughter and her 80-year-old mom

Armie with her daughter and her 80-year-old mom

Increased Anxiety and Worry

Affirming what Teodosio mentioned, Agnes confesses the stress and anxiety she experiences at work is compounded by the pandemic. “I know I have the choice to not tune in to the news, but I always worry about the effects of the government’s ineptitude on my family and loved ones. I sometimes think I may be getting too emotional and overreacting, but I’ve been feeling like this for quite a while. It’s hard to be in a different country with no support system.”

Even if she’s able to go home, Agnes would rather stay in Taiwan for several reasons. “Although my host country has handled the pandemic well, no one knows if you’ll be able to contract the virus in transit. I don’t have enough leave credits to do a long-period quarantine, and I certainly don’t want to spend Christmas in quarantine.” Though her family understands her decision, Agnes can’t help getting emotional. “The knowledge that I can’t be with my family on this important holiday is making me feel depressed. We sometimes have video chats and I’ve brought up the topic of missing them a lot especially in these stressful times, and they’ve been supportive to a certain extent. Nevertheless, it’s still a painful decision even if it’s a necessary one.”

Armie and Boyet with their kids in 2018

Armie and Boyet with their kids in 2018

Though Armie worries about her family contracting the disease, a temporary setback came in the form of her husband’s 5-month unemployment. “He works in a gym, which shut down during the pandemic. The gym is back in business now, but during those 5 months, I worried about making ends meet. Somehow, we did it by cutting back on expenses.”

November brought Typhoon Ulysses, which submerged their house in Bulacan. “My kids and my mom didn’t have electricity and drinking water for several days. I asked help from friends in the Philippines, who thankfully helped them out. Now, my kids are busy with house repairs.” Though her children are used to Armie and Boyet’s absence, Armie confesses that her heart broke when her husband asked them what else they needed. “My kids replied, ‘You. We need you both. Please come home.”’

Coping this Holiday Season

The combined challenges of the pandemic and the holiday season may be difficult, but they can be conquered. Our interviewees offer these tips:

Stay grounded. “OFWs need to be resilient during these trying times. Focus on the things that they can control such as their thoughts, emotions, reactions and behavior. So in a time of pandemic, they can do their part in keeping safe by following safety protocols,” says Teodosio.

Find a support group. While taking a leave from work to “unplug from the stress,” Agnes is going to meet up with Pinoy friends in Taiwan. “We’re planning to have Noche Buena together and watch the fireworks display on New Year’s Eve.”

Stay healthy. Agnes tries to cope by taking care of herself physically and mentally. She adds, “So when it’s safe to travel, I’ll be in a better state and be able to make up for lost time.” Teodosio advises OFWs to differentiate between good and bad anxiety. “Some anxiety may be productive; this is what makes us wash our hands often and socially distance ourselves from others and keep our masks on,” she explains.

Focus on the present. The OFW needs to take one day at a time. “Excessively worrying about the future for himself or his family can sometimes paralyze a person with fear,” says Teodosio. “Becoming aware and mindful of all his thoughts and feelings can be very helpful in managing these emotions.”

Connect with family. Armie and Boyet make it a point to virtually share the annual Noche Buena with their family. “I plan their meal, take care of the budget, and make sure they decorate the house. When midnight strikes, Boyet and I eat with them via video chat,” shares Armie. Teodosio encourages OFWS to maintain constant communication. “Trying to weigh the pros and cons of coming home can help the OFW and their loved ones in understanding what is more important to them—the health of the OFW or being together during Christmas. Having the patience for one another and thinking of what is best for everyone will help the families cope in these trying times.” Agnes affirms this: “Sometimes I feel helpless, but at least with the chats and messages, there’s still something I can do even if it’s a small thing.”

If you’re anxious or depressed, don’t hesitate to reach out to the following:

- Roselle Teodosio (psychologist) – 09166961223 and 09088761223 or email: selteodosio@gmail.com

- National Center for Mental Health Crisis – 09178998727

- Philippine Mental Health Association – 09175652036

- Philippine Psychiatric Association – 09189424864

In an effort to “build a kinder and more compassionate world,” the World Kindness Movement observes World Kindness Day on November 13 every year. It is “a day set aside to celebrate and appreciate kindness around the world.”

But how does one define kindness? This pandemic, simple acts of kindness like staying home and wearing a face mask can do a lot in curtailing the spread of the virus. Kindness can also mean getting to know something or someone beyond the general bias toward it—such as Wuhan City in Central China, which people all over the world now only know as the starting point of COVID-19. This World Kindness Day, we offer a different, kinder view of Hubei Province’s capital city.

It was once China’s capital.

From December 1926 to September 1927, Wuhan was the capital of the Kuomintang nationalist government. To create the new capital, China’s nationalist authorities merged the cities of Wuchang, Hankou, and Hanyang, from which Wuhan’s name was derived. However, the city lost its capital status when Chiang Kai-Shek established a new government in Nanjing.

It is directly related to the fall of Chinese monarchy.

The Wuhan Uprising in 1911 ended China’s last imperial dynasty, the Qing Dynasty. The success of the revolution prompted other provinces to follow, and in 1912, 18 more provinces united to form the Republic of China. The abdication of the Qing Dynasty the following month marked the end of the kingdom.

![]()

It is one of the world’s largest university towns and is a center for research.

With over one million students in 53 universities, Wuhan is considered one of the largest university towns in the world. It has 4 scientific and technological development parks, over 350 research institutes, and 1,656 high-tech enterprises.

It is referred to as the “Chicago of China.”

Chicago is a hub of transportation, which includes O’Hare, the most globally-connected airport in the US. Wuhan is similar in a sense that it offers transport to almost all parts of China. It is a center for ships and railways, with the Wuhan Railway Hub offering trips to major cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Harbin, Chongqing, and Guangzhou.

Mulan probably lived in Wuhan.

Some theories state that Hua Mulan, the legendary female warrior and well-known “Disney Princess,” lived in the Huangpi District of Wuhan. Some even say that it is her birthplace.

Famous Places

Wuhan is a popular tourist destination with centuries-old attractions full of history, culture and astounding views.

![]()

Yellow Crane Tower

The Yellow Crane Tower was built in 223 as a watchtower for King Sun Quan’s army. The tower was destroyed and rebuilt seven times during the Ming (1368 – 1644) and Qing (1644 – 1911) Dynasties, and in 1884, it was completely destroyed in a fire.

Rebuilt in 1981, the Yellow Crane Tower stands 51.4 meters tall and consists of five floors. Interestingly, it appears the same regardless of the direction it is viewed from. Not only is it one of the most prominent towers in the south of the Yangtze River, it is also the symbol of Wuhan due to its cultural significance.

Hubu Alley

Built in 1368, Hubu Alley is known as “the First Alley for Chinese Snacks”, and has since been serving traditional Chinese breakfasts, such as hot dry noodles, beef noodles, Chinese doughnuts, and soup dumplings. From the Yellow Crane Tower, it can be reached 20 minutes by foot.

![]()

East Lake Scenic Area

The East Lake can be found on the Yangtze River’s south bank and in Wuchang’s east suburb. Covering an area of 87 square kilometers, it is the largest lake within a Chinese city. The area is “formed from many famous scenic spots along the bank,” and attracts many tourists due to its scenery.

Well-known Food and Dishes

Wuhan’s local food is said to be a mix of the cuisines of Sichuan, Chongqing, and Shanghai, which make it “spicy yet full of flavor.” Here are three of its most famous eats:

Hot Dry Noodles (Reganmian)

This is Wuhan’s most famous dish and the first one that locals will mention. The dish, which is essentially “dry noodles mixed with sesame paste, shallots and spicy seasoning,” is eaten for breakfast and as a snack.

![]()

Doupi

Often sold as a street snack, doupi’s layers are either made of tofu skin or “pancake lookalikes”. Glutinous rice is combined with usually no more than three ingredients chosen from beef, egg, mushrooms, beans, pork, or bamboo shoots stuffed in between the layers. Once everything is assembled, doupi is pan-fried, making it crispy on the outside and soft in the inside.

Mianwo

Though donut-shaped, mianwo is salty—made of rice milk, soybean milk, scallions and salt.

Wuhan’s Downside

Even with its must-see scenery and mouth-watering dishes, Wuhan, just like any other place, is not perfect.

Crowds and traffic jam

With a population of around 11 million, Wuhan has the densest population in Central China and is the 9th most populous city in the country. Large crowds, traffic congestions, and long lines are unavoidable in the city.

Before the East Lake became the picturesque spot that it is today, it suffered from soil, water, noise, and air pollution for decades. Wuhan used to be a major manufacturing site, causing the lake’s water quality to be very poor, with outbreaks of blue-green algae and dead fish. However, through the years, its water quality has dramatically improved. Because of this, East Lake is now able to host swimming contests, and serves as one of the best attractions in the city.

Waste concerns

In 2019, street protests were carried out in Yangluo of the Xinzhou District by around 10,000 local residents rallying against the construction of the Chenjiachong waste-to-energy plant – an incinerator that the government planned to construct to handle the city’s waste. But the incinerator was said to emit cancer-inducing toxins, and was going to be built only 800 meters away from residences.

The Xinzhou District government tried to calm protesters down by assuring them that their voices will be heard in the decision-making process. However, reports said that government officials and the police went door-to-door to force residents to sign the project’s consent form, threatening them if they refused to do so.

From its cultural and historical prominence to its contributions to technological innovation, there is clearly more to Wuhan than just the coronavirus. Like any other city, it has its strengths and imperfections worth learning about especially during the pandemic and World Kindness Day.